The Assyrian Homeland

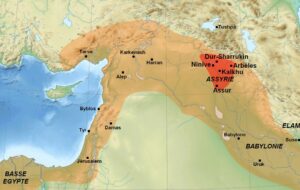

To the Assyrians, the ‘Land of Ashur’, the mat Ashur – a term first employed in the Middle Assyrian kingdom – embraced not just the Assyrian triangle but also the lands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that had been conquered in the 13th century BC. The loss of the latter to the Aramaeans reduced Assyria in the Dark Age to the core of the kingdom, a territory defined by a triangle of the cities of Ashur, Nineveh and Arbail.

To its north, the Assyrian homeland was bordered by the massif of the Taurus/Armenian Mountains. Behind this, there would emerge in due course what would become Assyria’s primary competitor in the region – the kingdom of Urartu – which is today in modern Armenia. To the east, running from the north and inclining to the south-east and far beyond the southernmost border of the kingdom, were the Zagros Mountains (simply called ‘the mountains’ in Assyrian times), whose spine reached down into the southern part of what is today Iran and which at this time was known as Elam. The Assyrians shared in common with all other Mesopotamian plain dwellers the fear of the numerous uncivilized mountain tribes who would periodically descend to ravage the richer lands below. Their existence generated a very definite collective fear and insecurity. This was especially true for Assyria given the proximity of its northern border to the foothills of the Armenian massif and to the east those of the lower slopes of the Zagros. This accounts for the frequent campaigning of Assyrian kings into these regions to ravage the tribes that lived there. The western boundary of Assyria was demarcated by the Tigris River.

The first capital of the kingdom was Ashur, whose ruins are known today as Qala’at Sherqat, where the Assyrian dynasty began. Named for Ashur, the supreme god of Assyria, the city was situated on a rocky outcrop on the western side of the Tigris. Although it would cease to be the political capital of Assyria in the reign of Ashurnasirpal II, it was to remain as its premier religious site and the city in which the Assyrian kings were crowned and subsequently buried until its fall in 614BC.

Nineveh lay about 100km to the north of Ashur and was built in proximity to a ford that became, for that reason, a major crossing point on the river Tigris – a factor that was to play a significant role in the city’s destiny. The site had an ancient provenance with archaeological evidence attesting to human settlement as far back as 6000 bc. By the beginning of the second millennium a major trade route that came from Anatolia and traversed the southern foothills of the Taurus Mountains crossed the Tigris at this point. Nineveh lay on the eastern riverbank and is today partially embraced by the modern city of Mosul. A further trade route, running from Syria in the west through to the crossing points of the Zagros Mountains and Iran farther east, made the site of Nineveh ever more important during the later Neo-Assyrian period when Sennacherib (704–681 bc) chose the city as Assyria’s new capital.

Some 80km to the east of Nineveh is Arbail, which is in turn c.105km from Ashur. Of the three cities of Ancient Assyria it is the only one that still remains. It is now known as Erbil and functions as the capital of modern Iraqi Kurdistan. The city is found on the western fringes of the Zagros Mountains and controlled several routes that went up into the mountains and on into Iran – and are still used today. Through Arbail also ran the main trade route from central Assyria down into Babylonia, which paralleled the lower slopes of the Zagros Mountains and the Diyala River.

All three cities were religious centres with temples to gods, the paramount of which was Ashur, it being the home of the national god and the site of the only temple dedicated to the deity. Both Nineveh and Arbail were identified with the goddess Ishtar who was venerated and worshipped as a protector of Assyria. This is reflected in a praise poem dating from the reign of Ashurbanipal (668–c.630BC):

‘Exalt and glorify the Lady of Nineveh, magnify and praise the Lady of Arbela [Arbail], who have no equal among the great gods’!

With an area of 75,000 square miles (194,249 square km), what constituted Ancient Assyria is quite large, being on a par with the contemporary African state of Uganda, bigger than modern Syria and slightly smaller in total area than Belarus.

The land of Assyria offered a marked contrast with Babylonia in the south, this being true of both ancient and modern Iraq. Below Ashur and the Lesser Zab River, and to the south of the low hills of the Jebel Hamrin, the transition to a much drier environment is quite apparent. Indeed H.W.F. Saggs, the eminent Assyriologist, likens it to travelling ‘into a manifestly different country’. Whereas in Assyria, agriculture was rain-fed, to the south in Babylonia ‘the land is flat to the horizon, and for the most of the year its sunparched earth is arid and dead’. The Assyrian heartland was highly fertile, a consequence of rains beginning in November and which could last through to April. The main crops were barley and wheat. Other crops grown in quantity included onions, flax and emmer. Assyria also had extensive areas of grassland and was able to raise large numbers of sheep, the plain around Nineveh being especially fertile. Such grassland was also employed in the later empire for the grazing of horses for the military.

The king was always concerned about the harvest, as the storage and consumption of barley, wheat flour and hay for the military was extensive. Throughout the Middle and Neo-Assyrian Empires numerous monarchs spoke of the improvements they wrought within the country to improve its agricultural output and with the onset of the empire after 745BC this became recurring motif in their Annals. As an early example from the late Middle Empire period, Tiglath-pileser I proudly declared: ‘I had ploughs put into operation throughout the whole land of Assyria, whereby I heaped up more piles of grain than my ancestors. I established herds of horses, cattle and donkeys from the booty which by the help of my Lord Ashur had taken from the lands over which I had won dominion.’

There was an integral relationship between the capacity of the Assyrian Army to wage almost annual campaigns and the harvest, especially at the outset of a campaign. However, once into enemy territory, the presumption was that the Assyrian Army would fall upon the resources of the lands they moved through. Following the beginning of an improvement in the climate in the latter part of the 10th century bc with the return of the rains and the regularized yield of the barley crop among others, Assyria could once again employ its army in aggressive campaigning, albeit in a limited fashion at first.

This period also saw a revival in Assyrian royal inscriptions detailing these campaigns, as the period of retreat and territorial loss had in no way diminished the Assyrian imperative to conquer. Apart from the rain-fed fertility of the land and its consequent agricultural output, Assyria had very few other natural resources to sustain the kingdom. The need to acquire the metals, stone and wood essential for the Assyrian economy was the primary drive behind Assyrian expansionism, though the urge to deny these resources to competitor states was also important. Although Assyrian expansionism between the 9th and 7th centuries BC was grounded in an imperialist religious-political ideology in which the kings of the land were tasked to expand it at the behest of the god Ashur, no matter how it was ‘dressed up’, at base the drive was fundamentally economic and was to remain so until the end of the empire.

These military campaigns were assisted by the fact that there were now no other major powers on the international scene who could successfully contend with the Assyrian state and delimit its aspirations once its process of expansion began. As one eminent Assyriologist has expressed it, ‘even in her weakened condition Assyria now towered like a giant over a multitude of dwarfs’.

Mark Healy is the author of The Ancient Assyrians: Empire & Army, 883-612BC, published by Osprey.