‘Specimens of Snobbery’: Cricket and the Hypocrisy of the Victorian Imagination

‘The national game of cricket,’ wrote Lord William Lennox in 1840, ‘has a peculiar claim to the people generally; and is one of those games open alike to all. It is free from selfishness, cruelty, or oppression; it encourages activity; it binds gentlemen to country life; it preserves the manly character of the Briton, and has been truly characterised as a healthful, manly recreation, giving strength to the body and cheerfulness to the mind, and is one of the few sports that has not been made the subject of some invidious anathema.’

As a sign of cricket’s place in the Victorian imagination, Lennox’s language is revealing. It is, first of all, a democratic game – ‘open alike to all’, as he puts it – a game in which lords and labourers can compete together in the same team. Cricket is ‘manly’, too, building the strength and the character of all those people – all those English people – fortunate enough to play it. But most of all, cricket contains a kind of moral purity – it is ‘free from selfishness, cruelty, or oppression’. In this distinctively Victorian vision, the game is no longer bound up with the vices or the corruption of society. On the contrary, it is an escape from such things – a haven of wholesomeness and noble instincts. In Victorian England, cricket was no longer just a sport. It was philosophy; it was virtue; it was an imagined ideal of nationhood. The game had been remade as a fiction, a metaphor for all the things England wanted itself to be.

*

By the middle of the nineteenth century, cricket had a significant role in the expanding public-school system. The game was no longer just a recreation to be enjoyed – it could be taught. More than that, it should be taught. Increasingly, cricket was being thought of as a technical discipline, a science that could be studied and mastered. And this was accompanied by another conviction, that cricket should form part of the moral education of the young. It was, after all, not simply a game, but something much more profound – a morally edifying pursuit, expressing the best of English values. A child who learned the ways of cricket could, in doing so, become a better citizen – a wiser and more noble human being

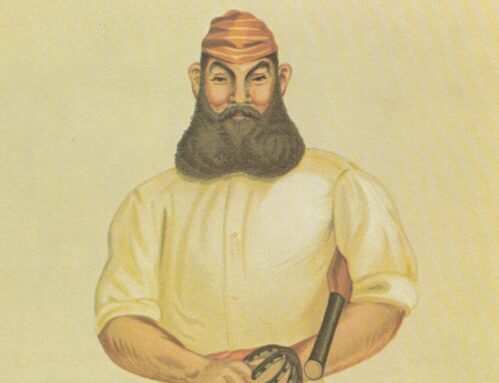

Nobody came to represent this idealised vision more than W.G. Grace, Victorian England’s greatest cricketer – a genius who dominated and revolutionised the game, and who became a hero to boys across the land. ‘England has no more popular game than cricket,’ ran a profile of Grace in The Boy’s Own Paper at the height of his career, ‘and cricket has had no greater exponent than William Gilbert Grace. For the last seventeen years his position in the cricket world has been unique . . . few bowlers have surpassed him, few fields have equalled him, no batsman has approached him.’

But the profile goes on to stress other things – an integrity and a strength of character – that existed as an example to all. ‘Let all our readers remember that if a thing is worth doing it is worth doing well; in work or in play earnestness is never wasted. The secret of Dr Grace’s excellence has been his thoroughness.’ Former cricketer and Whig politician, Lord Charles Russell, is then quoted: ‘Looking at Mr Grace’s playing, I have never been able to tell whether that gentleman is playing a winning or losing game . . . just as he plays one ball so he plays the game; he is heart and soul in it.’ Grace, in other words, was not just a great cricketer – he was a living embodiment of Victorian English virtue. Hard-working, dedicated and motivated by noble instincts, he was a moral as well as a sporting paragon.

It has now been amply documented that this romanticised view of Grace is some distance from the truth. The statistical transcendence of his career is undeniable; the numbers speak for themselves. But other elements of the man sit less well with the caricatured superman image. Even his imposing physical size, so suggestive of hypermasculine power, does not quite tell the whole story. As his biographer Simon Rae noted, ‘For so large and so obviously virile a man,’ his voice ‘was remarkably high-pitched.’ It was the source of self-consciousness and some embarrassment for the great man. On one occasion, he had a proposal of marriage rejected ‘because of his high, squeaky voice’.

Beneath the simplified vision of Grace as folk hero lies a much more complex story, one that is tangled up with the intricacies of Victorian England’s class struggles. Nowhere was this more apparent than on the inaugural 1873 tour of English players to Australia. The three-month trip was beset with problems. Travelling conditions were grim, and the Australian pitches often unplayable (Grace later recalled in disbelief how, on a Stawell pitch recently converted from a ploughed field, one ball jammed in the dust and never made it to the batsman). But most striking of all was the ill-feeling that developed between the England party and their Australian hosts. The team was greeted with excited cheers and large crowds upon their arrival in Melbourne; but the positivity did not last.

In particular, the Australian public were shocked by some of the snobbery they witnessed. A light was suddenly cast on England’s class divides – and it uncovered some ugly truths. ‘In the colonies,’ ran a column in The Sydney Mail, ‘I have always been led to believe that the cricket-field levels all social distinctions, but in England . . . a line is drawn between gentlemen and professionals, and in many cases the latter are made to feel their social position somewhat acutely’. Another columnist was more withering:

‘The gentlemen cricketers . . . trading on the professional cricketers of the team and endeavouring to secure for their genteel selves as much of the three thousand five hundred pounds of colonial money as they can . . . They will not even lodge at the same hotel with them! . . . The consequence of all this is what might be expected – insubordination in the ranks, a divided team, and humiliating defeats. We were not prepared to find such wretched specimens of snobbery as these amongst British gentlemen cricketers.’

The writer concluded by denouncing ‘the vulgar pretentious species of gentility set up as the Grace standard’. So-called ‘Victorian English values’ were nothing more than a sham – a veil for nastiness and arrogance. Before the tour, Grace had claimed that his team would have a duty ‘to uphold the high character of English cricketers’. Instead – as both captain and their greatest player – Grace was being pinned as the figurehead of English hypocrisy, an incarnation of Perfidious Albion.

And there were even darker accusations in the mix. Rumours circulated that the English team were throwing games, in a ploy coordinated by Grace himself. The Sydney Mail avowed that ‘the play of Grace and his team is looked upon with the utmost distrust, and even when they score an easy victory the public think they have all the more reason for saying that previous performances, where they were less fortunate, were not fair and above board’.

Grace had arrived on Australian soil as an idol and a legend. But by the tour’s end, things had turned sour in astonishing fashion. He was now pilloried as a puppet-master of sleaze and trickery. ‘Instead of his brilliant and skilful play being remembered with profit and pleasure,’ explained The Sydney Morning Herald, ‘his name will become a synonym for mean cunning and systematic fraud.’

Grace’s complicated story exemplifies the contradictions of cricket in the cultural environment of Victorian England. The game was hailed as a space in which people of all classes could play together in a single, unified team; at the same time, two distinct categories of cricketer existed – the amateur ‘gentlemen’ and the professional ‘players’ – determined not by a player’s skill or talent, but by their birth and background. And it was not simply a matter of each keeping to their own. A widespread feeling persisted that the amateur cricketer was in pursuit of something more noble – playing not for money, but for a love of the game and its artistry. The professional, in contrast, was a more mercenary figure; not just lowlier in social status, but lowlier in moral intention.

Few pieces of Victorian art captured this segregated culture better than ‘Gentlemen vs Players, at Lord’s in the Pavilion Enclosure’, a painting by Sir Robert Ponsonby Staples first exhibited in 1891. In it, the ‘gentlemen’ are all gathered in front of the pavilion. They are huddled closely together – as if territorial in spirit or conspiring and wanting not to be overheard. On several of them, the striped blazer and cap of Lord’s membership are visible. The signs by the gate make the point clearly enough: ‘For Members Only’. Not a single one of these gentlemen is deigning even to look at the ‘players’, who are gathering in the background of the picture, on their way out to the pitch. There is an eloquent geographical separation of the two groups; the pavilion’s picket fence stretching between them becomes a symbol of the players’ externality to the world of social privilege.

The background of the artist, Ponsonby Staples, could not have been much more aristocratic; he was the third son of Sir Nathaniel Staples, 10th Baronet of Lissan House in County Tyrone. But in the painting, the statement he makes about cricket’s culture of class-based division is sharp-edged. The amateurs may be given prominence, in the foreground of the picture; but as they sit around idly chatting, every one of them is cast into shadow. It is the players – out on the field, filled with purpose, ready to play some cricket – who are bathed in a sea of sunlight.

Brendan Cooper writes, primarily, on literature and sport and is the author of Echoing Greens: How Cricket Shaped the English Imagination and Deep Pockets: Snooker and the Meaning of Life.