The Roman

I

‘Roman Liburnian!’ called the lookout.

Captain Barzan of the Cilician pirate trireme Thalassa looked up, saw the direction of the pointing arm and the sleek Roman vessel it was indicating. He turned to the helmsman, ‘Come two points south. We can catch him before he reaches port.’ He raised his voice, bellowing. ‘Rowing master, standard speed, we’ll let the oars assist the sail and perhaps overcome the drag from the weed on Thalassa’s bottom. Slave master, the men may sing the rowing song.’

The whole conversation had been audible below and the slave named 44 began easing his oar out before the pausator rowing-master started to pound the rhythm on his drum and the hortator slave-master began to sing the rowing song,

‘HEIA, Viri, nostruim reboans echo sonnet HEIA!’

44 leaned forward swinging his oar into position, dropped the blade in concert with the other galley slaves and pulled with all his strength. To an experienced seafarer such as Captain Barzan, 44’s name carried as much information as a patrician Roman name establishing identity through a paternal forename, family name and third name based on something personal. The name 44 revealed that the slave was a thranite a galley-slave who sat on the uppermost of Thalassa’s three levels of rowing benches in a box that reached out from the ship’s side like a balcony on a building. That he was strong enough to control an oar in excess of twelve feet long. That he sat half way along the right side of the ship facing the stern. As 44 was one of the sixty two men who handled the most unwieldy oars, he needed the clearest view of the pausator and the hortator whose drum-beat and rowing song controlled rhythm and speed – until the ship went into battle and the singing had to stop.

More than a year at the oar broadened 44’s shoulders and corded his arms; his back was as strong as his massive thighs. Even though he was young his palms were as callused as anyone’s aboard. As, indeed, were his naked buttocks and the soles of his feet. Together with the other oarsmen, he could power Thalassa across the sea at ten knots, even when the bottom was fouled, as now, with barnacles, mussels and weed.

***

The Liburnian’s captain saw them coming and swung southward, racing towards the port of Rhodes. He was making almost seven knots under sail, but the wind was falling light. If he was going to get safely past the ruin of the Colossus, he was soon going to have to turn a few more points southwards and rely on his two banks of eighteen oars per side. Once that happened he would find himself utterly at the mercy of Thalassa’s three banks totalling eighty five a side, weed or no weed.

Captain Barzan looked down onto the main deck where his fifty-man crew waited, the deck-rail lined with pirates carrying grappling hooks. He glanced up once again, focusing all his attention on the Roman vessel that was his prey. It would be over in half an hour or so. Barzan, Thalassa and her crew would be richer by the worth of another hull and by whatever or whoever they found aboard worth selling at auction, in the slave markets of Delos or holding for ransom.

‘There!’ called the lookout once again. The Roman captain had turned one point too far away from the wind and it had deserted him. His empty sail flapped like a broken wing. The Liburnian’s sleek hull wallowed. Her oars came out and began to beat the surface in a vain attempt at escape. Too little, thought Barzan, and far too late. ‘Battle speed!’ he bellowed and the singing on the rowing decks stopped.

II

Half an hour later 44 sat with his oar on his lap, cold and dripping; the moisture from the shaft mixed with the perspiration running down his lower belly and the inside of his thighs. His seat in the upper and outer position meant that he overhung the Liburnian’s deck slightly. If he angled the oar-blade, he could see what was going on. The pirates jumped down scant feet away and he watched them go to work. The Liburnian’s crew were merchantmen not soldiers. Given the chance they would have surrendered before Captain Barzan’s men came aboard but they didn’t get the opportunity. Those who stood against the pirates were ruthlessly chopped down. The rest were herded across the red-running deck towards the forecastle, freeing the stern for the last of those who still wanted to fight: the captain, a couple of his senior officers and a young Roman passenger. He was in armour and laying about himself with a gladius but he lacked both helmet and shield. He probably had slaves and body servants below but he really needed a couple of stout legionaries to back him up.

It was brave, but 44 could see that the odds were far beyond anything the Roman could match. Would he elect ignominious life or glorious death? 44 knew which one he would have chosen. Footsteps thumped across the deck above 44’s head; the rail creaked as a sizeable body leaned against it. ‘Well?’ bellowed Barzan. ‘Make your minds up. Wind’s shifting, tide’s turning and I haven’t got all day.’

The Liburnian’s captain and senior officers threw their weapons down. Only the Roman stood firm, his eyes narrowed in calculation. The hulls groaned against each-other as a wave ran under them heading for Rhodes. The ropes attached to the grappling hooks hummed like lyre-strings. ‘Ransom Roman,’ offered Barzan. ‘We’ll keep you safe, feed you and water you at our own expense if you give us your word. You look as though you’d be worth a sestercius or two.’

The Roman still hesitated. One of the pirates stepped silently in behind him and hit him on the head with the pommel of his sword. The Roman crashed to the deck and his gladius spun away. ‘Good decision,’ said Barzan to the unconscious man. ‘Bring him aboard and let’s get going.’

***

44 was only able to hear what happened later that day after the Liburnian’s crew had been secured below and replaced by pirates so that she could follow in Thalassa’s wake. But he had seen it all before.

‘You can’t treat me like this!’ snarled the prisoner’s scholarly Greek. ‘I am a Roman citizen!’

‘OH!’ gasped Barzan, ‘A Roman citizen! If only we had known… What are we poor Cilician pirates to do in the face of a citizen of the Republic?’

There was a brief silence. The game could go one of two ways now, thought 44. If the arrogant Roman took Barzan at his word he would be stripped, given sandals and a toga, shown to a ladder down the ship’s side and sent on his way – for, as every Cilician pirate knew, there was nothing a Roman citizen could not do. Including walking on water.

But this Roman, it seemed, was no pompous fool with an over-inflated opinion of himself. ‘You’re mocking me!’ he said. ‘An entire ship-full of pirates cowed by one man – Roman citizen or not! You are simply laughing at me!’

‘We are indeed,’ answered Barzan cheerfully. ‘Let’s hope we do not also laugh at your ransom!’ He paused. ‘We were thinking twenty talents. Silver.’

‘Twenty talents,’ replied the Roman. ‘Have you no idea who I am? I am worth at least twice that. Send to my friends in Miletus and they will supply forty talents at least. No! Fifty. Silver!’

‘We’ll be happy to do as you advise!’ answered Barzan. ‘Fifty talents it is!’

‘But be warned,’ continued the Roman. ‘When the money is paid and my freedom is restored, I will return with a fleet. I will track you down, I will take back my silver. And I will crucify you all.’

After the laughter died down, 44 heard Barzan demand, ‘By what name should we know our Nemesis?’

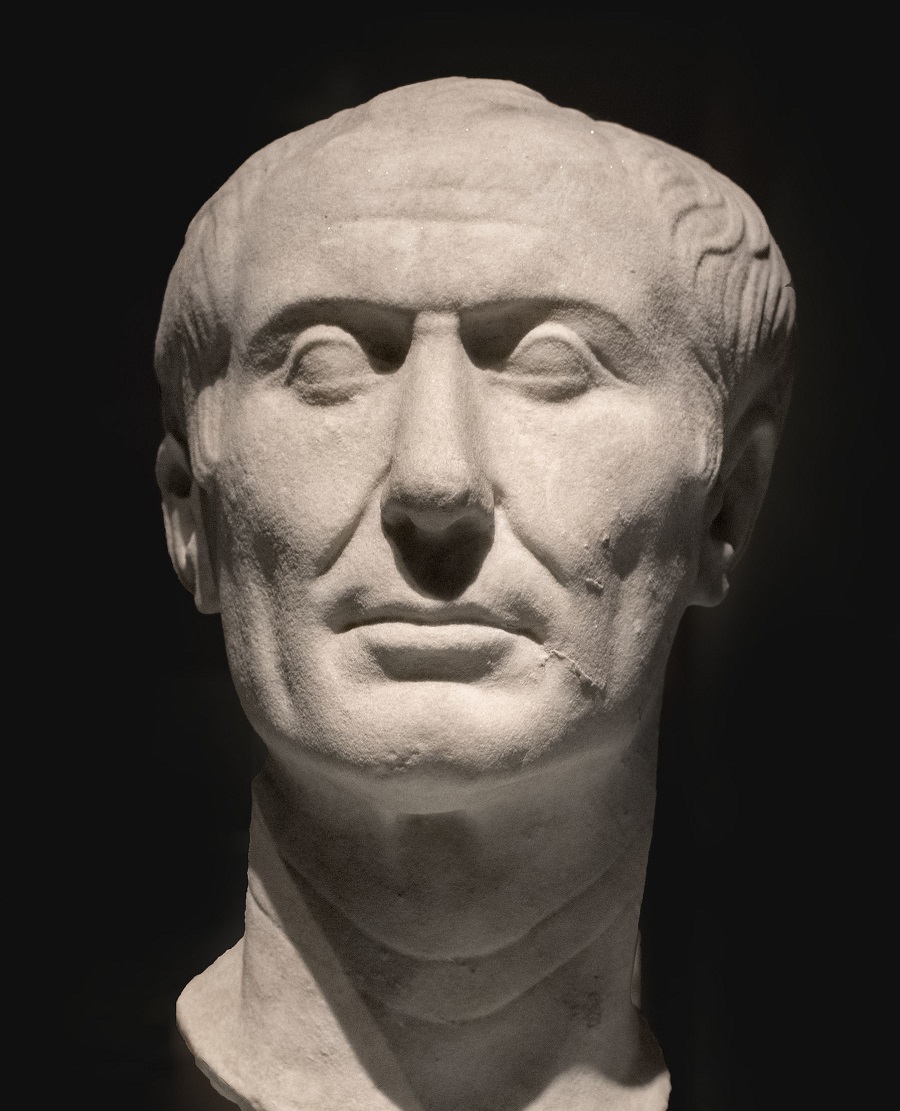

‘I am Gaius, son of Gaius of the Julii family which owes its direct descent to the Goddess Venus Victrix. And, in honour of a distinguished ancestor famous for single-handedly killing an elephant, I am also known as Caesar.’

‘So, young Gaius Julius Caesar, we have a bargain. You owe us fifty silver talents for your freedom…’

‘And crucifixion for having interrupted my journey to Molon’s school of oratory in Rhodes,’ concluded the Roman grimly.

III

‘Let us consider, fellow senators, the damage that piracy does to the Republic,’ said Gaius Julius Caesar. His voice, echoed across the anchorage. ‘How many ways does this iniquitous pastime hurt Rome and her citizens? Obviously, to begin with, it is responsible for the damage to legitimate trade and the theft of Roman goods, leading to the ruin of Roman commercial enterprises. Furthermore…’

44 listened to Caesar’s speech, inflicted on the pirates because he could not practice it with the famous elocution teacher Molon whose most notable recent pupil was Marcus Tullius Cicero. Thalassa sat at anchor in the makeshift harbour of Barzan’s favourite inlet on the pirate island of Pharmacusa after the better part of a fortnight running north. She sat there alone, for the captured Liburnian, stripped of her officers and crew, had been sent to Miletus with the ransom demand. Teams of slaves dived beneath Thalassa to clean her hull while her crew repaired her upper works, masts and rigging. Barzan’s success relied on the way he maintained his ship and treated his galley-slaves as well as upon the fierceness of his crew. Recent times, however, had been lean and hard. But now the promise of Caesar’s ransom meant he had time and space to indulge in repairs and clean the foul hull while everyone took a well-earned rest. The galley slaves sat on the sand under lackadaisical guard.

The guards were apathetic because the day was hot and the slaves sluggish. In any case there was nowhere to run to on Pharmacusa except to other pirate captains in other bays – most of them far worse than Barzan. Or to the forested peaks of the island’s hilly spine, compared with which the sea seemed more inviting. But few slaves, like few sailors, could swim and anyone risking the waters who didn’t drown immediately would probably find themselves food for the sharks.

Except for the team cleaning Thalassa’s hull, most of the galley-slaves sat mindlessly, glad that they had been able to wash as they waded ashore and grateful that they were out of the ship as their rowing benches were sluiced and the bilges purified. But 44 was thinking of much more than current ease. He understood that the captive awaiting his ransom was different to anyone Barzan had held before. The crew might have been amused by the Roman’s arrogant ways since the ransom demands had been sent out but 44 remembered the threat of crucifixion. And, while the others found the warning just another element in the Roman’s amusing pomposity, 44 believed Caesar had every intention of carrying it out. Furthermore, he reckoned that when the Roman returned with his ships and his soldiers, a quick-thinking young galley-slave might grasp a chance at freedom.

44 allowed Caesar’s Greek elocution to sweep over him, reminding him of his youth, even though it had an Athenian accent and 44 was a Spartan who had been brought up in the old ways which were little more than legends recounted to Roman tourists these days. He had strangled a wolf with his bare hands before he slept with his first woman. He was extremely adept at killing and had been captured by the slave traders who sold him to Barzan as he sought to finish the rituals of manhood and join a kryptaeia secret service unit by killing his first man. Although on the one hand he was still a helpless galley-slave, on the other he was a fully- fledged Spartan warrior who would have been perfectly capable of standing with Leonidas and his Three Hundred at the gates of Thermopylae.

‘Shit,’ said the hortator, staring out to where Thalassa sat on the silvery bay. ‘That’s another slave gone. It’s just impossible to keep a close eye on them all.’ 44 sat up and squinted. There was a body floating face-down beside hull.

‘We’ll never clean her keel at this rate,’ said the gubernator. The two men shook their heads.

Another piece of 44’s plan fell into place.

***

‘Sails!’ called the lookout late next morning. ‘Two vessels hull-down on the horizon.’

‘It has to be our Liburnian,’ said Barzan. ‘Coming back with the ransom and a ship to take our prisoner home.’

‘It’d better be the ransom,’ growled the gubernator. ‘I wouldn’t give an obol for Caesar’s chances otherwise. One more speech and they’ll tear him to pieces like the mad Maenads ripping Orpheus to shreds.’

‘True enough,’ agreed the hortator. ‘He hasn’t made any friends with all those endless fucking speeches. And as for the poems…’

Caesar’s pirate audience stirred as the Liburnian and its companion approached. ‘What!’ he bellowed. ‘I haven’t finished my speech! Will you Cilician clods just sit and listen…’ But the promise of so much money – after more than a month of listening to Caesar – was too much to be controlled.

The Liburnian docked first but her crew called that the silver was on the other vessel. The second ship was immediately invaded by excited pirates. Sure enough it carried fifty silver talents, each weighing about the same as a man, which were carried onto the rudimentary dockside by the triumphant pirates. Caesar finally gave up on his speeches and shouldered his way up the gangplank greeting and being greeted by the men who had come to free him.

As soon as the weighty talents had been unloaded and checked, Caesar returned to the head of the gangway. ‘After thirty-eight days of my captivity, things are finally settled between us,’ he called down to Barzan. ‘My slaves and body-servants have packed away everything I brought with me. They will now bring my possessions aboard so that I can leave you and return to Miletus. But remember what I promised. I will be back!’

He departed Pharmacusa to hoots of derisive merriment. Even the slaves laughed.

Except for 44.

IV

‘That bloody Roman may have handed us a poisoned chalice,’ said Barzan to the gubernator, his oldest friend and most trusted companion. ‘This amount of silver on an island full of pirates is likely to draw unwelcome attention.’

‘What can we do?’

‘We can’t keep it here and guard it ourselves, especially as I want to set sail again as soon as possible. Nor can we keep it aboard Thalassa. Everyone would be more worried about losing this treasure than about getting even more. We had better hide it.’

‘On the island?’

‘Up in the hills. I’ve been planning this ever since that arrogant Roman offered an unmanageable fortune as his ransom. I wouldn’t be surprised if he hoped we’d kill each-other as we all tried to get it for ourselves!’

‘No, Captain, that can’t be true – he’s going to come back and crucify us; that’s his real plan!’

The two men had a good laugh at that.

44 did not share their amusement. It was not hard to eavesdrop on them as long as his actions weren’t too obvious. He was only a galley-slave after all – a thing of no account, so easy to overlook.

‘You’ll need two men per talent to carry it, though – that’s nearly half the oarsmen,’ said the gubernator when their hilarity died down.

‘We’ll put it all aboard the Liburnian for the time-being. Tie her up by the dockside so no-one has to carry anything too far. Set a well-armed guard. Then we can do it over the next few days as we get Thalassa re-rigged, clean and ready to sail. Ten men. Five talents a time. Ten visits to my hiding place. Problem solved.’

‘Ten men? Why so few?’

‘I trust myself not to give the location away. And I trust you. But I can’t trust anyone else. So we’ll choose the ten worst oarsmen. Ones we won’t miss when we set sail again. They’ll take the talents up and we’ll isolate them each time they come back – but they won’t be coming back from the last excursion at all. Besides, the work on Thalassa’s hull is progressing more slowly than I calculated. We have time to do it little by little.’

***

‘I can swim,’ called 44. ‘I’ll go and work on the hull. Better than sitting here day after day getting eaten alive by sand-flies…’

The slave-master hesitated. 44 was his best oarsman – too good to risk. But then again, it was well over a week since Caesar left and time was running out along with Barzan’s patience. The last of the talents was due to be moved tomorrow, the captain wanted to leave as soon as possible after that and Thalassa was not yet clean.

44 waded into the water and leaned forward when it reached his waist, swimming out to Thalassa with powerful strokes. He pulled himself up the nearest ladder and a crewman handed him a chisel and a hammer. ‘I’ll need these back,’ he warned. ‘The captain wants a careful count kept.’

44 nodded, took a deep breath and dived beneath the trireme’s keel. Several other figures were at work, their bodies blurred by the water. There were three teams. One armed like him with hammer and chisel attacking the barnacles encrusting the hull. Another with short knives cutting the strings of mussels free and scraping the remnants the chisels left. And a third with long, sharp knives whose job was to hack the weed free so the others could get at the mussels and barnacles. Timing it so that he moved only when he was unobserved, 44 left his job and began to search the sea-bed below the ship. The last slave floating face-down would have been too busy drowning to give his equipment back. But there was nothing he could use as a weapon there – the crew were clearly being very careful indeed. He was called in at day’s end and given extra food with the rest of the surviving divers.

He was back in the freezing water soon after dawn and once again he had no trouble leaving the others unobserved. It took him one lung-bursting breath to swim underwater to the shelter of the dock. He hid there until he heard Barzan bring the ten slaves to retrieve the last five talents, then he slid out of the water and began to exercise some of the skills he had learned as he grew up. Using the bushes for cover, 44 followed them up into the hillside forest. Unarmed, naked and thankful for the gathering heat of the morning, he flitted through the forest, haunting the laden sailors’ footsteps like a fantasma.

In the past, it had taken the oarsmen most of the daylight hours to carry the silver away, conceal it and return. But it didn’t take that long to discover where the treasure was hidden. 44 watched them as they began to conceal the last five talents then he returned to the dockside, slid back into the water and went to work under Thalassa having been absent for three hours, his jaunt unnoticed by the bored and listless guards on shore or aboard.

Barzan returned alone mid-afternoon. By evening the cleaning of Thalassa’s hull was complete. 44 was among the team that pulled the trireme to the jetty and secured her beside the Liburnian. ‘Right,’ announced Barzan. ‘Both crews and slaves eat and rest tonight. Board Thalassa and our new Liburnian at first light tomorrow and we will be out on the hunt by sunrise.’

44 was awake with the first of Thalassa’s crew as the sky began to lighten. Under the direction of the pausator and the hortator they found their places, sat on the familiar benches and slid the oars out. Barzan himself came aboard last. ‘Right!’ he bellowed, his voice carrying to the Liburnian. ‘Lets go!’ The oarsmen eased the vessels out into deeper water, then swung Thalassa round so that she was heading for the opening of the bay.

But no sooner had the pausator set the rhythm than the captain called, ‘All stop!’

The slaves sat still and silent, wondering what was going on. They didn’t have to wait long to find out. One of the sailors leaned down, one hand on the pausator’s drum. ‘There’s a fleet of Roman triremes blockading the bay!’

‘It’s that bastard we ransomed,’ growled the pausator. ‘Come back to crucify us all. Just like he said he would!’

44 found himself nodding in agreement, scarcely able to control his excitement.

‘What shall we do, Captain?’ The gubernator’s question was just audible.

‘Let me think!’ snarled Barzan.

Fight! Thought 44. Fight and die with honour! But he knew very well that Barzan would never do that. He had too many friends amongst the crews. He loved Thalassa and would never see her or the Liburnian rammed, fired or falling back into Roman hands. He even had some kindness for 44 and his companions. No. Even before Barzan realised the inevitable, 44 knew that he would try and bargain with the Roman who had become their nemesis after all.

V

‘If you release us, I will return the ransom,’ offered Barzan.

‘You are a mere pirate,’ came Caesar’s icy answer. ‘So I can hardly expect you to understand the concept of honour. But when a man of the Julii gives his word, he keeps it no matter what the danger or the cost. I said I would return: I have. I said I would bring a fleet: I have. I said I would crucify you and your crew. I will. Whether the ransom is returned or not.’

Some whim of Caesar’s made him hold the negotiations with Barzan on the dockside in front of the Cilician captain’s condemned crew and the two sets of galley-slaves who had powered Thalassa and the Liburnian – whose fate was yet to be decided. Though 44 suspected they were all bound for the slave markets at Delos – especially if Barzan went to Hades without revealing where the ransom was hidden. Marines from the fleet blockading the bay formed a wall of steel around the captives. The morning was ominously still, the sky a steely blue; away in the west there was a wall of black thunderheads: bad weather on the way.

‘Very well, then,’ spat Barzan with the courage of a cornered rat. ‘If we die anyway then you can whistle for your fifty talents!’

‘I could torture the information out of you,’ Caesar pointed out. ‘I have carnifexes adept in the use of whips, hooks, hammers and hot irons.’

‘Would that be honourable, Caesar? You promised crucifixion. There was no talk of butchers or branding irons.’

‘Very well,’ said Caesar. ‘Let it be so.’

The fleet’s carpenters made short work of preparing fifty crosses. Long before the black clouds were overhead they were laid out on the dockside. Barzan and his crew were lashed in place while the galley slaves dug pits deep enough for the crosses to stand in once they were pulled erect. The carpenters returned with long nails and heavy hammers.

44 had joined the team digging the hole for Barzan’s cross. He knew Caesar would take a personal interest in the captain’s execution. The carpenter rested his first nail on the pale flesh of Barzan’s right wrist beside the rope that held it immovably in place. He raised the hammer ready to drive it through and into the wood beneath. Caesar appeared. ‘Take special care,’ he said. ‘There are vessels in the wrist that allow a swift and easy death if they are cut. I do not want them cut. Death must not come too easily for this one.’

‘As you say, dominus.’ The carpenter drove the nail down between the veins and arteries in the pirate’s right wrist, through the tendons, bones and skin, deep into the wood. Then he did the same to the left wrist. Barzan grunted and groaned but he did not cry out until the nails smashed through his ankles.

***

Some time later, Barzan and his crew were hanging, their shattered ankles perhaps two Roman feet above the ground. Their bodies pulled forward by the weight of their heads, shoulders and bellies, their arms reaching back like the wings of birds about to take flight, chests fully expanded by the position, breathing almost impossible. Even so, Barzan fought to have the last word. ‘Look at us, Gaius Julius Caesar! Your stupid Roman arrogance may have cost us our lives but it has cost you fifty talents. The weight of each man hanging here. In silver!’

44 stepped forward, his movement just enough to catch the Roman’s eye without disturbing the guards. ‘Kyrios, Lord,’ he said quietly. ‘I know where your silver is.’

Caesar turned. He saw a tall, broad-shouldered young man – perhaps five years his junior. His unkempt hair curled into ringlets of red gold. The beard beginning to cover his chin shone with copper highlights, as did the hair matted on his chest, belly and groin. His face was not delicate – strong rather than beautiful but striking nevertheless. His eyes were dark brown with the strangest reddish tint. Caesar was by no means proof against male beauty. So he was willing to indulge the interruption.

‘You know where the ransom is hidden?’

‘I followed them as they hid it, kyrios.’

Barzan came to his galley-slave’s aid – by accident rather than design. ‘You treacherous bastard,’ he spat, heaving his body into agonising positions so he could catch sufficient breath to speak. ‘I should have made you one of the slaves who carried the treasure and slit your throat at the end!’

‘Just so,’ said Caesar with a cold glance at the snarling man. He looked back at 44 as the captain choked back into silence, almost suffocated by what he had managed to say. ‘And what do you want in return for showing me where the treasure is?’

‘My freedom. I know you will send the others to the slave markets on Delos. Give me my freedom.’

‘Your freedom? That’s all? For the weight of fifty men in silver? No reward? No weapons? No clothes? No way off the island?’

‘I can find all these for myself, Caesar. Once I am free. All I need is your word. The word of a man of the Julii.’

‘Very well, you have my word. What will you need to retrieve the fifty talents? Carts?’

‘No, kyrios. It is hidden where only men on foot may go.’

‘Men then. Will a hundred be enough?’

‘Yes, kyrios.’

‘You have them. But slave, you also have my word on this: if you are trying to trick me, if this is a ruse to allow you to escape and my silver is not returned, then I will hunt you as I have hunted these pirates and when I catch you, you will beg for an easy death like your captain and his men are enjoying.’

‘I am telling the truth, kyrios. I will lead your men to the hiding place and we will return with your silver.’

Caesar nodded and as he did so, the first great flash of lightning came with an immediate clap of thunder as though a volcano was exploding into life nearby.

Afterward

‘He was a good captain,’ said 44, looking up at Barzan’s rain-drenched corpse hanging on the cross. ‘He treated us slaves well enough.’ The thunderstorm was pulling away but the last of the rain pounded down onto the men loading Caesar’s silver aboard Thalassa, which was secured beside the Liburnian at the dockside and which was also the Roman’s property now, along with the slaves who rowed her. All except for one of them.

‘Your fellow slaves tell me you are known as 44,’ said Caesar. ‘And sometimes Spartacus – the Spartan. These are not good names for a free man; I could not write either on your manumission papers. What name were you known by before you were taken and enslaved? What name did your father give you at your birth?’

‘I never knew my father or the name he gave me. I was found on a hillside in Sparta as a baby and taken in by shepherds. They called me The Gift of Artemis, because she is the goddess of childbirth and wild places. They called me Artemidorus.’

‘You have much to learn, young Artemidorus,’ said Caesar as he signed the papers freeing 44 from slavery. ‘You should not judge men solely by their actions. You also need to understand their motivations. The captain treated you slaves well, but only because he needed you fit enough to power his vessel. Had he needed you to die, you would be dead like the men who carried his silver; like the men who drowned careening his ship.’

The Roman’s gaze grew distant, as though he was considering something far away in distance or time. ‘Consider, if a man is standing behind you with a dagger in his hand, it is his motivation that is important. If he is motivated to kill you, then his actions are hardly relevant, all except that one. No matter how friendly he might seem to your face; no matter how sympathetic or sycophantic – his motivation is all important. Every time he does not stab you in the back is merely one step nearer to the moment when he will stab you in the back. Do you understand?’

‘Yes kyrios, I understand,’ said Artemidorus as he took his manumission papers. ‘You should never let anyone carrying a dagger come too close to your back.’

Peter Tonkin is the author of the Caesar’s Spies series of novels.