Crime in Victorian London

One of the settings for my new novel, The Jaggard Case, is Clerkenwell – the scene of the arrest of Oliver Twist for pickpocketing. Clerkenwell was famous not only for its jewellery and watchmaking industries, but also its criminality and dreadful poverty. In 1847, The Illustrated London News did not mince its words: “the dingy, swarming alleys, crowded with sodden-looking women, and hulking unwashed men, clustering around the doors of low-browed public houses… where thieves drink and smoke. The burglar has his crib in Clerkenwell…” The reporter went on to say that Clerkenwell “is remarkable for crimes of the darkest kind… more murders take place in Clerkenwell than in any other part of London…”

He refers to the dilapidated property and the “foul and ugly rubbish” filling the street and gutters, and to the undersized and undernourished children with “pale and ghastly faces, forms hideous with premature disease.” Fever was everywhere, as The Sun newspaper reported, created by the overcrowded graveyards, the piggeries, and the overflowing gutters and cesspits.

It seemed the right place for my criminal, Martin Jaggard and his coining confederates. There was plenty of gold and silver to steal and plenty of abandoned children to be used and abused. Inspector Shackell observes to Dickens that Fagin is still about. The reference is, of course to Oliver Twist, published in 1837. My novel is set in 1851. In The Household Narrative of Current Events, January 1851, the supplement to Household Words, there is an article from the newspapers describing “A Den of Juvenile Thieves” discovered in Islington under a railway arch. The den was furnished and even had a fireplace and “a cooking apparatus.” Inspector Shackell is right. The gang of boys was arrested and sent to prison for three to six weeks. As Dickens knew very well, when they were released, they would resume their criminal activities elsewhere. In the same year the Household Narrative reports the case of two boys, aged 14 and 10, arrested for stealing a loaf of bread. Their heads “scarcely reached the top of the dock.” Their defence was that they were starving. They were sentenced to be whipped in the House of Correction in Clerkenwell. The fourteen-year-old James Cook had begun his criminal career at the age of eight. In another case, Thomas Ellis, aged ten, had been convicted eight times as had another boy, twelve-year-old John Collins. After his last offence, he was transported for ten years. All versions of the juvenile Jacko Cragg I invented for Jaggard’s gang.

There were some infamous gangs of boys who terrorised their neighbourhoods. I based Jaggard’s boys on the notorious Golden Lane Gang, one member of which was well-known in Clerkenwell, and came before the magistrate for stealing handkerchiefs, but the gang was a particularly brutal one. They carried 16” long sticks loaded with lead at the end. In 1851, a man who tried to rescue his son from the gang was beaten up and struck in the mouth with a stick. Residents of Golden Lane were reported as being too frightened to leave their houses and no stranger would pass unmolested. In another case in 1851, they terrorised a shopkeeper by throwing potatoes at his windows and his assistants. The shopkeeper was brutally beaten when he tried to remonstrate with them.

Abandoned girls were particularly in danger of being drawn into prostitution; even girls with homes and parents were lured away from home or kidnapped and kept prisoner under the power of the brothel keeper who had clients who asked for untouched girls. Superintendent Jones’s servant girl, Posy, is kidnapped with the help of Phoebe Miller, accomplice to the kidnappers. There were cross-Channel traffickers who took girls to France and Belgium where they, too, were kept captive, and there was traffic from France and Belgium to England. Boys and girls were used by coining gangs as messengers, look-outs, and for their little fingers which were useful for pouring the molten metal into the moulds – there were several cases of children being badly burnt. In one case, a child died from drinking vitriol (basically sulphuric acid) which was used in the making of bad money.

Coining, known as ‘the yellow trade’, was rife in London and in the provinces and I found many cases, ranging from small ‘family-run’ businesses to large-scale operations run by master criminals, including the case of the Paris coiners, a gang run by a ruthless Spaniard, who escaped the police. He recruited his workforce from the gutters and told them that “henceforward you are my creatures.” If they betrayed him, death would be their fate, probably by having their heads crushed. The Spaniard masqueraded as a gentleman and called himself a count. A Belgian man escaped when another Paris gang was broken up. My Martin Jaggard dresses as a gentleman and has contacts on the continent. There were plenty of stories of the forging of foreign currency in London, too. In 1851, a case was brought against an Italian immigrant for the forgery of Austrian banknotes, and in 1845, two men were prosecuted for forging Russian banknotes. A case involving forged Belgian banknotes occurred in 1842.

The forging of banknotes was a much more professional business than coining which often took place in the most squalid back rooms and attics, carried out sometimes by just two or three people making shillings or sixpences. Bank notes demanded more investment and skill which is why a trained engraver was essential; enter the out-of-work engraver, Thoddy Cragg – another bad lot. A printing press was necessary, too. Highly skilled engravers and printers could print a good enough facsimile of a Bank of England note that would be difficult to spot even by an expert. The paper was the problem, but that could be stolen if the gang had a man on the inside. The most famous case occurred in 1861 when paper was stolen from the Laverstoke paper mill in Hampshire where Bank of England paper had been manufactured for years.

There are two articles on banknotes in Household Words in September 1850, written by Dickens’s sub-editor, Henry Wills, which give the history of the trade. Banknote forgery began in 1797 when the Bank of England circulated one-pound notes instead of golden guineas. At that time, it was easy to make good money, easy to buy goods worth five shillings, offer your dud pound note and walk away with fifteen shillings profit. In 1817 there were 870 prosecutions bank note forgery. By 1850, forgeries were less numerous, but cases continued to be prosecuted.

Dickens began writing Bleak House in November 1851, when he was settled at last in Tavistock House. In June 1852, Bell’s Weekly Messenger carried a review of the story so far, praising especially the portrait of Jo, the boy crossing-sweeper:

“Mr Dickens invariably shows that few public abuses escape his observation… touching upon the neglected condition of those poor creatures, the ragged boys of London, who know no parents and no home…”

Jo is just one boy, but he is an emblem of all the neglected children in London at that time, many of whom were drawn into crime because, like the two mall boys in the dock, they were starving. Dickens wrote of “the darkest ignorance and degradation at our doors.”

While I was looking into matters of forgery, gangs, and wild boys, I was distracted – all too easily – by the following newspaper article about two arrivals into St. Katharine’s Dock on November 24th, 1851:

“a brace of gigantic young elephants, a male and female, purchased in India. They will be put into training immediately and make their debut as soon as they will be accomplished in the novel roles they are to sustain.”

I had to read on – after all, Dickens and Superintendent Jones were bound for St. Katharine’s Dock in pursuit of a witness. The elephants were destined for Astley’s circus which was situated in Lambeth on the south side of the Thames and famed for its equestrian performances. In 1853, Mr William Cooke’s elephants were advertised to appear in an entertainment entitled The Magic Gong – my elephants, I wonder. Aside from the natural revulsion I felt as a modern reader at the idea of performing elephants and elephants enduring such long sea voyages – as much as five months – as a writer I couldn’t help being tempted to think about how I might squeeze – perhaps not the right word – them into the story. What novel roles might they play in The Jaggard Case?

What I had not realised until I continued my browsing into elephants was that there were so many elephants about in Victorian London. I thought I had discovered something amazing, but there were elephants all over the place, in the Regent’s Park Zoo, in menageries, on stage, in travelling circuses, even a “Wonderful Performing Elephant” to be seen at the Adelaide Gallery. This was a huge automaton, I was glad to discover.

By 1828 elephants could be seen at Regent’s Park Zoo. In 1828 there was a picture in the Mirror of the Indian elephant in his bath. Jack who came in 1831 was very popular, and a stall sold cakes and buns, especially for his consumption. Jack lasted almost twenty years despite his unsuitable diet and died on 6 June 1847. Dickens’s friend, the artist, George Landseer, brother of the more famous Edwin – he of the lions in Trafalgar Square – made an illustration of Jack for The Illustrated London News. One elephant did escape onto the quay at St Katharine’s Dock and went on the rampage – good for him, I say. He was eventually caught and tethered and went on his way to Regent’s Park Zoo where he lived a blameless life. Betsey, and her infant, Butcher – who turned out to be a girl -were brought from Calcutta with another elephant intended for Jamrach’s.

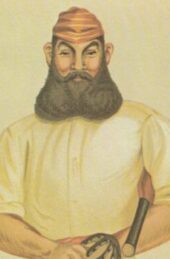

Johann Christian Carl Jamrach was the most celebrated animal dealer in London – his shop was on the Ratcliffe Highway just opposite the London Docks into which, of course, the animals came. You could buy anything from Jamrach – a tiger would set you back £300, a giraffe cost £40. Camels were cheap by comparison – £20. Buy one, get one… perhaps not. D. G. Rosetti bought his pet wombat from Jamrach. It slept in a lamp shade bowl.

William Herring of Quickset Row who appears in The Jaggard Case kept a menagerie with peacocks, wild cats, and other exotic beasts – not on the scale of Mr Jamrach, however. It was from Mr Herring that Dickens acquired his pet raven and who stuffed it for him when it died.

Though Dickens wrote about Grip in his letters praising its eccentric talents, it was not popular with Dickens’s children whose ankles it very often pecked. Dickens gave the name “Grip” to Barnaby Rudge’s pet raven in the novel of that name.

An unwelcome pet was the eagle given to Dickens by his friend, the painter, Robert McIan – a token of esteem, it seems. At least it wasn’t an elephant. However, Dickens wasn’t too keen on his new pet and passed it on to Edwin Landseer who kept a variety of animals at his home in St John’s Wood – not lions. The model for the Trafalgar Square lions was a dead one from the Regent’s Park Zoo where in 1849 Dickens saw the hippopotamus, Obaysch, about whom he wrote in Household Words. Obaysch, who had his own heated pool, appears in my novel, At Midnight in Venice – Landseer’s eagle is there, too. Obaysch was so popular that a Hippopotamus Polka was danced in London drawing rooms. Betsey and daughter, Butcher, however, proved serious rivals, and a Punch cartoon showed “The Nose of the Hippopotamus put out of joint” by little Butcher.

And my brace of gigantic elephants destined for Astley’s? Oh yes, they’re in – hugely material witnesses. Who’d have thought? A chance encounter with two elephants and case closed.

JC Briggs is author of The Charles Dickens Investigations series. The latest is The Waxwork Man.