Peter Tonkin, It’s that time of the year and we’re at the Ides of March – what is it about the assassination that fascinates you?

I’m sure there must be many turning points in history where chance or fate seemed to take a hand, but the assassination of Julius Caesar seems to me to present perhaps the clearest example. The plotters appear to have made little secret of their intentions and yet Caesar apparently remained ignorant of the threat. He was in fact warned by a note handed to him on his way to Pompey’s Theatre (see below) but by chance he never read it. The assassins had really made no plans for action if the assassination was successful and seem to have been almost as surprised (stunned?) as everyone else when he actually died. They had no real clear practical idea of what the ‘Freedom’ his death promised was going to look like – and there was the complete Roman Republic up for grabs!

The Death of Caesar

Your hero of the novel, Artemidorus, is in a race to save Caesar from his end. How did you manage to maintain excitement throughout the novel, when we all know about the successful assassination?

I hoped to blend a series of plotlines together. Centrally, the story is told almost entirely from Artemidorus’ point of view and he, of course, doesn’t know Caesar is doomed. He just knows that a slave from Brutus’ household has information about the assassins’ plans that is so vital it must be taken, via his tribune, to his General, Master of the Horse Mark Antony and via Antony to Caesar. His attempts to follow this line are constantly frustrated, generating tension in itself. Also importantly, the city through which Artemidorus moves is a character and I have tried to present it from communal toilets via fire-trap insulae to the great villas and palaces of the rich in a way I had not seen it done before. In parallel with that, I was extremely careful to present the events of the fatal day, hour by hour, precisely as they occur in the latest updates of the historical record.

Was Artemidorus based on any real-life people?

The name is that belonging to the man who really did hand Caesar a list of his assassins on his way to the fatal Senate meeting. He was probably a Greek mathematician visiting Brutus at the time. I took some liberties however and turned him into James Bond.

The Ides is the first of a five part series, culminating in the battle of Philippi, and Mark Anthony’s defeat of Brutus and Cassius – do you have a favourite of the five?

Two. The last two, which form one complete story chronicalling Antony’s (actual) attempt to get Cleopatra to send him a fleet while Cassius with a sizeable army was waiting on the Egyptian border, considering the possibility of an invasion. Readers have remarked on the abrupt ending of Road To War – but Death at Philippi begins (literally) one second later and reconstructs the campaign leading up to the battles of Philippi – in which fate or chance once again played a considerable part, as it had in Caesar’s death.

Caesar, much like a certain contemporary figure, was thought to be invincible and was declared Dictator Perpetuo. Since your novel deals with the build-up – when do you think the assassins decided he had to go?

I agree with the traditional assessment which has its roots in Plutarch. The most likely trigger-point was when Antony offered him the crown of Rome at the Lupercalia festival in mid-February, almost exactly a month before the Ides of March. This would have particularly outraged Brutus who was very proud of the fact that his ancestor had been credited with driving the last King of Rome (Tarquin the Proud) out of the city four centuries earlier, thus creating the Republic. Brutus became the ‘face’ of the movement, though it actually seems to have been driven by Cassius, Albinus and the Casca brothers. Cicero loudly bemoaned the fact that he was not invited into the group. Had he been, things would have turned out differently – he would have murdered Antony as well, for a start!

What were the sources/writers you used for research?

Of the modern historians, I relied upon Stephen Dando Collins (The Ides) and Barry Strauss (The Death of Caesar) and Sir Ronald Syme (The Roman Revolution) most closely. On a different level I also filleted Colleen McCullough’s The October Horse. Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar played an important (if not quite accurate) part. Then there were Plutarch, Suetonius, Appian, amongst others, Cicero and Julius Caesar himself.

You’ve recently written Shadow of the Axe and the Tudor era – do you think you’ll return to the Roman period?

If I can, I would love to. The current volumes are really only the first section of a longer series in which I had planned to have Artemidorus and his various associates follow Augustus, Anthony and Cleopatra through as accurate historical reconstruction as I could manage from Philippi to Actium and (briefly) its aftermath. I had envisaged a closing scene to the entire series where Artemidorus, disguised, delivers the fatal poison in her monument to Cleopatra (whom he has always truly loved).

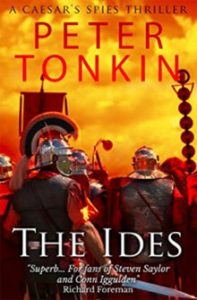

Peter Tonkin is the author of over 40 novels. The Ides, the first of his Caesar’s Spies series, was published in 2018.

Peter Tonkin Peter Tonkin