Alexander the Great in the Dock

At The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in London, on 26th October 2022, Alexander the Great stood accused of terrible crimes against humanity, the indictment of which can be found here. I witnessed the televised proceedings as Alexander III of Macedon sat, making no sound but shaking his head forlornly, as the four counts were read out:

Count 1: he ordered the extensive pillaging and/or destruction by the Macedonian Army of the city of Persepolis, which was not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly, in violation of the laws and customs of war;

Count 2: he ordered the wilful killing en masse by the Macedonian Army of those Persian civilians present in the city of Persepolis;

Count 3: he ordered or permitted the enslavement en masse by the Macedonian Army of female Persian civilians present in the city of Persepolis;

Count 4: he ordered or permitted the destruction of the palace complex, a historic monument, when this was not imperatively demanded by the necessities of war and was not a military objective.

Alexander, looking somewhat bedraggled, unshaven and dressed in a lumberjack shirt, sat impassively for much of the proceeding. The temptation to settle the matter in his customary way must have been strong, but it is to his credit that he remained calm throughout.

The eminent Philippe Sands KC, author of The Ratline, led for the Director of Athenian Prosecutions, but the case did not seem strong against “Mr the Great”. Using legal argument from 1946 Nuremberg trials was a brilliant move – had Alexander been living in 1946. Unfortunately for Sands, though luckily for Carthage and Rome, he had died 2,344 years earlier in 323BC.

Now it was the turn of Patrick Gibbs KC, and piece by piece he dismantled the case presented by the prosecution, using their own argument; no eyewitnesses, unlike at Nuremberg; no contemporary evidence, unlike at Nuremberg. There was the rather difficult fact that all the evidence relied on writers from 400+ years after the event. These eyewitnesses “read books…written by people who had spoken to people who may have been there…” Gibbs was keen to see these books, but sadly the prosecution had to admit they had been lost. “An ancient excuse.” responded Gibbs, mournfully.

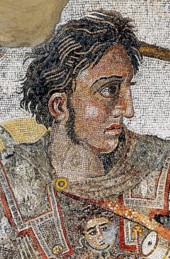

Alexander at perhaps his finest victory, Gaugamela in 331BC

The argument the prosecution had employed against Alexander, was that the four counts constituted a war crime. Even taking into account the flimsy evidence, Gibbs asked the jury to imagine being in the Macedonian soldiery. Having described the traumatic events of the Battle of Persian Gates, when the roles at Thermopylae were reversed, and then the struggle to enter the city of Persepolis, Gibbs had constructed an emotional piece of rhetoric, which brought a tear to the eye of at least one viewer.

When the not guilty verdict on all four counts arrived, it was overwhelming – and this was despite a last minute attempt at steering the jury the other way by Supreme Court Justice Leggatt.

What a hugely entertaining and educational exercise, not only in ancient Greek history, but in modern day legal debate. All participants performed their roles admirably (even Lord Leggatt), and Classics for All has continued the moot trials as is their tradition – previous accused have included Socrates, Antigone, Boudicca and Lysistrata. The trials can be replayed here.

Classics for All was established to reverse the trend of the subject in state schools. In 2010, only 25% of state schools taught Classics (the figure is 75% in private schools), and the charity’s mission is to reverse that decline. Classics for All encourages the teaching of Latin, Greek, Ancient History and Classical Civilisation in state schools across the country, with many in the most deprived areas. You can find out more about Classics for All’s great work here.

Oliver Webb-Carter is the Editor of Aspects of History.