The Second World War saw a desperate conflict between Allied and Axis scientists, who were locked in a deadly arms race to develop new technology – in what Winston Churchill called the Wizard War.

To gain the upper hand in this secret war, the Royal Navy formed a specialist intelligence assault unit to raid Axis bases and to move ahead of an Allied advance to capture material before it could be destroyed.

The unit was the brainchild of Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, who at the time was the Personal Assistant to Admiral Godfrey, the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Fleming named the new formation ’30 Commando Unit’ after his secretary’s room number in the Admiralty Building. Although the unit had many names, Fleming called them his “Red Indians”. They became known as 30 Assault Unit at the end of 1943, and 30 Advance Unit in 1945.

The inspiration for 30 Commando is said to have come when Fleming visited ‘Camp X’ in Canada, where agents for the Special Operations Executive and the American Office of Strategic Services were taught the arts of ungentlemanly warfare. Fleming was so impressed that he decided to create a similar ‘private army’ for the navy.

The formation of 30 Commando Unit also emerged in response to the German use of Intelligence Commandos (Abwehr-Truppen) in Crete and Athens, where they pulled off several intelligence coups against the British.

Additionally, there had been a number of British actions to capture enemy technology, which no doubt played a role in developing the idea. These were driven by the desperate need to crack the Enigma code and overcome German advancements in radar.

The first was Operation Claymore, a commando raid on the Norwegian Lofoten Islands in March 1941. The principal targets were German fuel tanks and a fish factory, but there was also a secondary mission to attack a German weather trawler. This was successfully executed, resulting in the capture of rotors for an Enigma machine, as well as the Enigma settings for the Home Waters network—something for which Bletchley Park had been desperate. Two months later, sailors from the destroyer HMS Bulldog boarded the surfaced U-110 and captured an Enigma machine before the boat sank.

Ian Fleming had even proposed Operation Ruthless in 1940, a fantastic scheme to crash a Heinkel 111 bomber in the English Channel to try and capture an Enigma machine from a German rescue craft. The formation of an intelligence commando unit was a more realistic proposition.

Fleming submitted the idea to Admiral Godfrey a few weeks after Operation Biting, a raid carried out by British paratroopers in February 1942 that successfully captured the new German Würzburg radar from an installation at Bruneval, on the French coast.

Biting no doubt highlighted the importance of such a unit and the project was approved by Combined Operations Headquarters in July 1942. 30 Commando was formed on interservice lines, with three troops of roughly 20 to 30 men, recruited from the Royal Navy, Army and Royal Marines. The recruits came from a variety of backgrounds, possessing the self-reliance and unique skill sets needed for such a specialist role. Two notable recruits were the Arctic explorers Quintin Riley (who led the unit in 1943) and Patrick Dalzel-Job (who joined in 1944).

The recruits went through the usual commando training, with more unconventional courses introduced by Fleming. This included safe cracking, lock picking, building searches, specialist photography, submarine technology, and radar and radio equipment.

Generally, they operated in small, independent sections of 6 to 8 men. They included technical and intelligence specialists to identify and collate the material while the Commandos acted as bodyguards and shock troops. Although the specialists would also take part in assaults when required.

The unit was first deployed during the Dieppe raid, where they didn’t get off their boats in the ensuing disaster. 30 Commando had more success when they took part in Operation Torch. Landing in Algiers, they captured an Enigma machine that had been configured for use by the Abwehr. This allowed Bletchley Park to crack German intelligence traffic.

However, it was during Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, and its subsequent operations in the Bay of Naples area that 30 Commando really began to make a name. Many of these exploits inspired my novel Hunter Class.

30 Commando landed in Sicily on 9 September 1943, under the overall command of Quentin Riley. They disembarked near a radar station along the west coast. After a brief exchange of fire, the German operators surrendered and blew up the station. But 30 Commando did manage to recover some equipment and documentation.

Other teams operating in Sicily were able to locate and capture an intact radar installation with all its handbooks, logs and codes, as well as a Telefunken VHF radio transceiver and its supporting documents. W/T (Wireless Telegraphy) stations were also raided throughout the island.

30 Commando stayed with the advance up the coast entering Augusta, just after Paddy Mayne’s Special Raiding Squadron had made their hair-raising landing in the port. 30 Commando raided the Italian Naval Headquarters, capturing an Enigma machine and other important intelligence material.

They travelled to the Trapani naval base on the other side of Sicily and found a massive haul of sea mines. These were examined by naval officers to discover the latest developments the Germans had made. Something of vital importance to the ongoing war at sea, where sea-mines were causing significant losses.

After taking part in the invasion of the Italian mainland at Salerno, 30 Commando started operations in the Bay of Naples area – in search of Italian underwater technology. A field in which the Italians excelled – and their equipment was streets ahead of the Allies.

These advances especially with regards to human torpedoes and limpet mines had enabled their elite Decima Flottiglia MAS to pull off some stunning commando raids. The most famous of these were against merchant shipping in Gibraltar Harbour, and they also severely damaged HMS Valiant and Queen Elizabeth in Alexandria Harbour.

The Decima Flottiglia MAS also carried out clandestine missions against Allied shipping in neutral Alexandretta, on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. Like other neutral cities, Alexandretta was a hotbed of intrigue, with all the combatant consulates plotting against each other. In this febrile atmosphere, Sub-Lieutenant Luigi Ferrar, a Gamma Swimmer from the Decima Flottiglia MAS, spent the evening of 30th June 1943 playing beach bowls.

When night fell and any watching spies had long since grown bored and wandered off, Ferrar coolly swam out to the harbour and placed two limpet mines on the steamship Orion, which was carrying a vital cargo of chrome. The limpet mines were of a groundbreaking design that would not detonate until the ship was at sea, so the crew would think they had been torpedoed or had hit a mine. I drew heavily on Ferrar’s feat in my novel.

The Decima Flottiglia MAS also had plans to attack New York Harbour. They intended to use a new prototype of a ‘pocket’ submarine that would be taken across the Atlantic by a mother submarine.

Mussolini’s government fell after the invasion of Sicily, and there was a fear that Italian underwater research would fall into German hands, in the ensuing power vacuum. It could then be used to bolster the Germans’ own considerable advances in submarine warfare, with untold consequences for the Battle of the Atlantic and the coming invasion of France. It was 30 Commando’s task to prevent that from happening.

30 Commando docked in Capri’s Marina Grande harbour on 12 September 1943, unsure if they would have to make a forced landing. They were relieved to be greeted by a band playing ‘It’s A Long Way to Tipperary’ and the town mayor.

They quickly got to work capturing the head of a stay behind operation, along with his codes and list of agents. They also captured a signal station and discovered Italian naval codes that should have been surrendered by Italy’s new government along with its fleet, after Mussolini’s fall.

The next day 30 Commando landed on the island of Ischia where they set up a base of operations and worked with the OSS, to further their hunt for enemy technology.

The OSS received a tip-off from an Italian refugee about the location of Admiral Minisini the Head of Underwater Research and Italy’s leading expert in torpedoes, and the inventor of many of the items they were hunting.

30 Commando raided the Admiral’s torpedo testing facility on San Martino islet, off the coast of the Phlegraean Peninsula in southwestern Italy. Led by Lieutenants Berncastle and Glanville, and Captain Martin-Smith, they captured Admiral Minisini – along with many of his blueprints and documents – from right under the noses of the Germans.

To expedite the Admiral’s cooperation, they agreed to take his wife and her extensive baggage train. In order to ensure a clean getaway, Captain Martin-Smith assisted Signora Minisini with her packing and spoke to her in German, pretending to be a German officer, as she was believed to have German sympathies.

After questioning the Admiral on Capri, 30 Commando raided the testing facility a second time, exploring its underground complex and raiding a nearby Y station, furthering their haul of intelligence.

30 Commando carried out additional raids on the Italian mainland, capturing everything from codebooks and radar equipment to prototype mines, torpedoes, and even a ‘pocket’ submarine.

They may have denied the Germans the Italian research, but Admiral Minisini, twelve of his engineers, and 40 tons of ‘loot’ were procured by the OSS and taken to a torpedo research station in Rhode Island. In what was a precursor to Operation Paper Clip – the American plan to track down German scientists after the war and take them back to the USA.

How the British allowed Minisini and such a large amount of material to slip through their fingers remains a mystery. I put forward a possible tongue-in-cheek explanation in my book.

Despite that setback, 30 Commando had proven themselves to be a highly effective unit for gathering intelligence and technology – a role in which they would excel in later campaigns, at the sharp end of the Wizard War. This was most notable in the search for Hitler’s new Wunderwaffe, or ‘wonder weapons’.

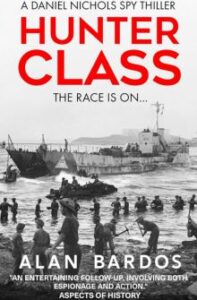

Alan Bardos is the author of historical fiction set around the World Wars. His latest novel is Hunter Class, which was published in November.