When a Single British Colony Ruled over a Quarter of Humanity

This spring, tensions between India and Pakistan reached their most perilous point in decades. With skirmishes erupting along their shared border and nuclear rhetoric flaring on both sides, the region remains one of the most militarised zones on earth, and its frontiers are so heavily fenced and floodlit that they can be seen from space. But it was not always like this. Just under a century ago, none of these borders existed.

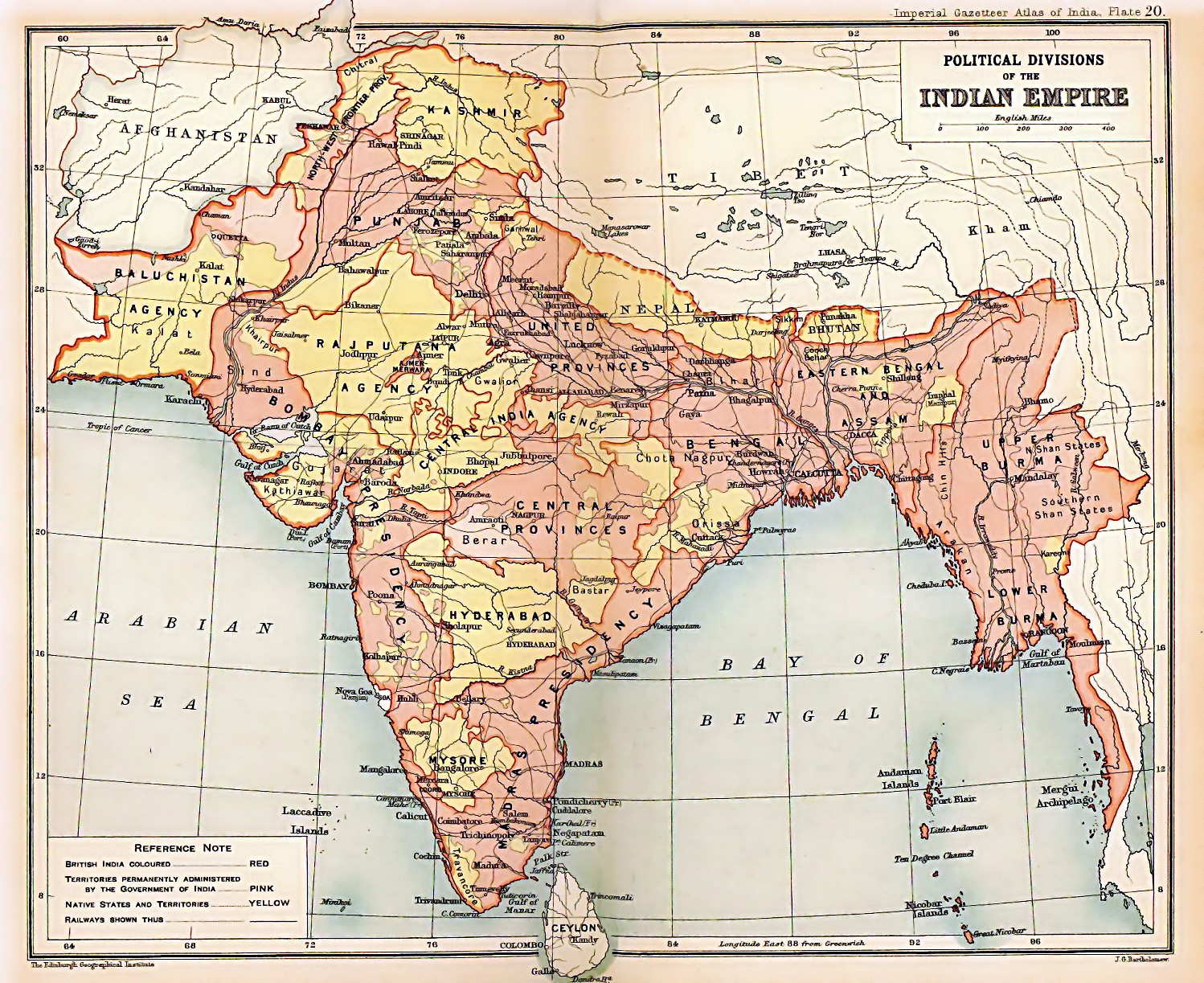

To understand how a land once ruled as a single unit, where millions fought shoulder-to-shoulder for freedom, has fractured into rival nations pointing missiles at each other, we must return to a forgotten imperial map. For nearly a hundred years, a single British colony known simply as “India” stretched from the Arabian Peninsula to the borders of Thailand, governing a quarter of humanity under a single bureaucratic umbrella.

At the start of 1928, however, few could have imagined how rapidly the Indian Empire would unravel. To most, the Raj still seemed an unshakable force, its dominion stretching across continents. Indeed on the first day of that year, as snow, sleet and rain showered down onto the streets of London, the British Empire tried for the very first time to reach into the stars.

Britain’s new public radio service, the BBC, had been founded a few years earlier, and as tens of thousands of people tuned in that morning, they could make out the voice of a man with a clipped London drawl. ‘Hullo all stars and nebulae,’ he began. ‘A greeting to all friendly planets circling with us on the everlasting tour.’ Have ‘our waves’ reached you yet?

A pause followed as the broadcaster waited for an answer to arrive from the stars, but none was forthcoming. ‘Reply if you please,’ he entreated, but again silence ensued. ‘London’s Message to Mars: No Reply Received’ was the main headline on newspaper stands that week.

Instead of speaking to aliens, therefore, the BBC presenter changed tack and turned to address the people of the Empire, from London to Toronto and from Cape Town to Calcutta. As well as addressing ‘the colonies’ more generally, a message from King George V was specifically directed to ‘the people of India’, who represented four-fifths of the British Empire and a quarter of the planet’s total population. ‘I reciprocate your earnest hopes,’ the king told his Indian subjects, ‘that 1928 may be the dawn of a new era of peace, happiness and prosperity to you all.’

The ‘India’ that King George was addressing that day was almost twice as large as modern India, yet today, its scale has been largely forgotten. Indeed this single colony ruled over a quarter of all human life on earth, and included the modern-day nations of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal, Bhutan, Kuwait, Oman, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and South Yemen. Maps showing its full extent were classified as secret; British officials feared that displaying India’s role in administering Arabia or the Himalayas might offend other imperial powers. Indeed as one lecturer at the Royal Asiatic Society joked, “As a jealous sheikh veils his favourite wife, so the British authorities shroud conditions in the Arab states in such thick mystery that ill-disposed propagandists might almost be excused for thinking that something dreadful is going on there.”

Nonetheless, in 1889, the British Parliament passed the Interpretation Act, classifying this vast territory, from the Red Sea to the borders of Thailand as ‘India’. It was the British Empire’s crown jewel, and encompassed the largest Hindu, Muslim, Sikh and Zoroastrian communities on the planet. Its people used the Indian rupee, were issued passports stamped ‘Indian Empire’, and were guarded by armies garrisoned in forts from the Bab el-Mandab to the Himalayas.

But over the next five decades, five partitions would fracture that single colony into a dozen different countries, displacing tens of millions, and reshaping the geopolitics of the modern world.

The shattering of the Indian Empire began in 1937, when the first largely forgotten partition carved Burma out from India after the Simon Commision argued that its residents were ethnically distinct from the rest of India. Many Hindus, including Gandhi, agreed, on the basis that an independent ‘India’ should match the boundaries of the ancient Hindu holy land ‘Bharat’, a land that didn’t include Burma. Yet many Burmese nationalists, including the influential monk Mahatma Ottama, opposed separation and believed that Burma would be politically orphaned without India. They were right, and the partition triggered famine, anti-Indian pogroms, and the mass expulsions of migrants. The Rohingya – Muslims in Burma’s Arakan crisis who had hoped to join Pakistan rather than Burma – would be just one of the communities divided by the new border.

A second partition – the partition of the Arabian Peninsula from India – began the same year with the separation of Aden from the Indian Empire. And yet as late as March 1947, the states of the Persian Gulf were still administered by the Indian Political Service. But a member of the British legation in Tehran even wrote of his surprise at the ‘apparent unanimity’ of ‘officials in Delhi … that the Persian Gulf was of little interest to the Government of India’. In hindsight the negotiations read like India’s greatest lost opportunity, willingly giving up the combined oil wealth of Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and the UAE. Indeed, were it not for this separation, most of the Arabian Peninsula except for Saudi Arabia might have become part of India or Pakistan after independence.

In 1947, tensions between India’s majority Hindu community and the enormous Muslim minority culminated in what might be called the ‘Great Partition’ of British India, and the creation of Pakistan out of the Muslim majority districts in the east and west of the subcontinent. As the country was torn apart, India descended into violence on an epic scale, precipitating the largest forced migration in human history. Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal has called it ‘the central historical event in twentieth-century South Asia,’ one that continues to inform how a quarter of the world ‘envisage their past, present and future’.

A fourth partition – the Partition of Princely India – occurred the same year. At the time of independence, nearly 40% of the subcontinent was not directly ruled by the British but by local monarchs, the so-called princely states. There were over 560 of them, ranging from vast territories like Hyderabad and Kashmir to tiny fiefdoms with just a few thousand people. Contrary to popular perception, less than half of the modern India-Pakistan border would be drawn by the British administrator Cyril Radcliffe. Instead, roughly 81 per cent of India’s border with West Pakistan would be determined by the decisions of seven princes and 36% of the border with East Pakistan by another ten. Only Hindu Bikaner was unequivocally eager to join the dominion that aligned with its ruler’s religion. For all other states, it was a matter of pragmatism. Which new country could offer the best deal? The borders of South Asia – usually understood as a legacy of the British – are as much the legacy of India’s princes, and many more states made a bid for independence than is traditionally acknowledged. Conflicts in Kashmir, Baluchistan and Manipur all have their origins in this partition.

Finally, a fifth partition came in 1971, the most significant year in the history of post-colonial South Asia. Though united by religion, East and West Pakistan were separated by over a thousand miles of Indian territory, and their cultural, linguistic, and political differences proved insurmountable. The breaking point came after the 1970 elections, when the Bengali leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman won a majority but was denied power. A brutal military crackdown called Operation Searchlight followed.

The nine months following Operation Searchlight would see people from all classes and backgrounds dragged into multiple conflicts, risk nuclear war between the USA and the Soviet Union, and ultimately change the entire map of South Asia. The precise order of events is heavily controversial, and even the basic vocabulary is disputed. Bangladeshis speak of a ‘Liberation War’, Pakistanis talk of a ‘Civil War’, and India of the ‘Third Indo-Pakistan War’. Statistics are equally contested, with the Bengali death toll varying wildly from three hundred thousand to three million. What is more certain is that in a matter of months, some ten million refugees crossed into India, and that, by the end of the year, hundreds of thousands of people had been rendered stateless. Pakistan would be cut in half, and the fifth partition of the former Indian Empire would carve its way through the subcontinent. The war of 1971 was a conflict that – just as much as 1947 – made South Asia what it is today.

***

Even as new borders were being drawn, people assumed that cross-border relationships and trade would continue as before. For more than two millennia, South Asian communities and their cultures had spread out across Asia into China, Afghanistan and Arabia, and from East Africa to Southeast Asia. As European empires were torn apart in the 20th century, these ancient social and commercial links could have been rekindled. But instead new national identities only hardened. Countless communities found themselves on the wrong side of new borders, leaving a series of suppurating wounds that continue to bleed into the present.

Thanks to revolution and social upheaval, the history of the Indian Empire sank into the depths of numerous national archives. In this way, separated by international and academic borders, one incredible tale has itself been partitioned into several very different narratives. Partition was not an event which ended in 1947, and the divides across South Asia grow ever wider. Politicians today still stoke its embers for their own ends with the now nuclear-armed nations of India and Pakistan teetering on the brink of all-out war. In Burma the military continues its assault on the Rohingya minority.

The last decade has witnessed the decline of globalisation, the strengthening of borders and the resurgence of nationalism across the world. India’s Partitions are a dire warning for what such a future might hold.

Sam Dalrymple is a historian, film-maker and the author of Shattered Lands: The End of Empire and the Making of Modern Asia which was released in June 2025.