When writing The Secrets of Hartwood Hall, I wanted to look at the position of women within the Victorian period – and I wanted to focus on the women who didn’t quite fit in to. the social structure. I gave my protagonist, Margaret Lennox, two roles that place her in an ambiguous social position within the Victorian world. Like the heroines of several Victorian novels, she is a governess. Unlike the heroines of most Victorian novels, she is also a widow.

Victorian society saw marriage and housewifery as the end goal in life for women; in the minds of many, man’s role was in the outside world and woman’s in the home. This was a society where women were meant to be wives, or effectively pre-wives: before having a husband, women were supposed to be waiting for one.

Of course, most people’s lived experiences did not fit neatly into these ‘ideals’. Many women did not marry. Many women married, then lost their husbands. Many women, both married and unmarried, worked away from the home. The ‘angel in the house’ was a middle-class preoccupation, based on a household having sufficient income that only one person need work. Those who set the ‘ideals’ of the time, being chiefly middle- and upper-class men, could just about make their peace with working-class women working, but the idea of middle-class women working unnerved them – which meant that governesses were a problem.

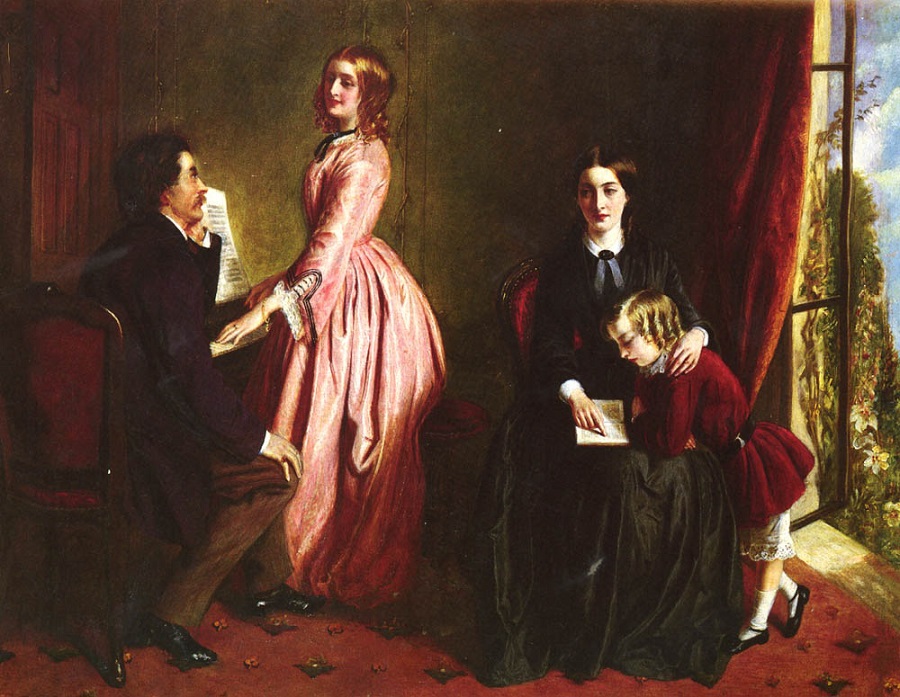

After all, a governess was an unmarried, educated woman earning money and building a career by her own intelligence. She was neither one of the servants nor one of the masters. She had to be a lady in education and manners but an employee in status. She was both in paid employment but also brought into contact with respectable gentlemen whom (God forbid!) she might marry. All of this made the Victorians anxious. In Jane Eyre, Lady Ingram declares: ‘Don’t mention governesses; the word makes me nervous.’

Victorian literature is full of governesses. Sometimes they are scheming to marry gentlemen far above themselves, as in William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. Sometimes they are downtrodden women struggling with difficult positions, as in Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey. Sometimes they live on terms of equality with their masters and mistresses, as to a certain extent in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre or Anthony Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds. The Victorians kept writing books about governesses, because they didn’t know what to make of them.

Widows, like governesses, unsettled the Victorians. In a society that saw women as wives and pre-wives, widows were post-wives: women who had been but were no longer married. Widows were more financially and socially independent than either married or unmarried women; they were single and respectable but also sexually experienced – and Victorian society couldn’t make its peace with a woman being all of these things.

Widows are rarely the heroines of Victorian novels, although there are notable exceptions, such as Trollope’s Barchester Towers. They frequently appear as secondary characters, however. The widowed woman seeking artfully to persuade men into matrimony became almost a stock figure in Victorian novels. Prime examples are the titular character in The Widow Barnaby by Frances Trollope or Mrs MacStinger in Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son. Only a relatively small percentage of widows remarried in mid-19th century Britain, but from their portrayal in literature, you would think otherwise.

Through Margaret, the protagonist of The Secrets of Hartwood Hall, I wanted to explore the complex identities that came from the roles of widow and governess in the Victorian period. Margaret was a governess in her youth, then left a difficult position to marry – but now, three years later, her husband is dead. She values her new independence but cannot escape a strong sense of guilt. With no other way to earn her living, she returns to work as a governess.

Margaret forms a kind of friendship with the mistress of the house, Mrs Eversham, but she is also very much in her power, always anxious about offending her. Like many governesses of the time, Margaret has nowhere to go if she loses her job. Her relationship with the servants is ambiguous, too. As she begins a friendship, and later more, with the gardener, Paul, Margaret is aware that this crosses all kinds of social lines, that she is breaking every rule.

Like many real women of the Victorian period, Margaret struggles to behave as society expects her to. As a governess and widow, she is already half outside of the structure – and she starts to wonder what kind of life she could have if she simply left it all behind.

The Secrets of Hartwood Hall by Katie Lumsden is out on 30th March.