23rd April 1813

Samuel Burrows was more excited than ever. Today was going to be his day. He had held the position of Chester’s, and therefore Cheshire’s, executioner for four years. However, until this day, only a select few knew of his official duties. For all of those years, he had enjoyed anonymity as he hid behind the black curtains above the gatehouse of the New City Gaol. There was one occasion that he remembered vividly and was thankful that no one knew it was he who pulled the lever that opened the trapdoor in front of a crowd of thousands.

On this occasion, his anonymity was a saving grace. It was his first execution, and it served to remind him that if anything could go wrong, then it more than likely could. As he prepared the nooses for the two condemned men, he went for a cheaper rope. It proved to be a fateful error as the two plummeted beneath him, only for the ropes to snap as George Glover and William Proudlove hit the floor beneath them. It was Burrows’s first time on the gallows, and the embarrassment consumed him. He was forced to do it again to ensure that Glover and Proudlove would not gain a last-minute reprieve. The second time around, Burrows made sure that the rope was thicker.

Now, there would be no place to hide if things went wrong as Chester prepared for its most high-profile execution to date. The curtains that had protected both Burrows and the condemned from the gaze of the general public were now removed. Finally, Burrows could reveal himself as Chester’s executioner, and he was salivating at the prospect and the celebrity that could finally be his.

For the execution of Edith Morrey, the authorities of Chester ensured that any remaining empathy from the crowd would be completely extinguished. Found guilty of the Petit Treason of her husband, George, in 1812, she was provided with a delayed execution due to her pregnancy. Now that her baby boy was born, she would be launched into eternity. The local papers had done a solid job in ensuring that the whole county loathed her for her crime as she convinced her younger lover, John Lomas, to kill her husband. Whilst never directly involved in the murder of her husband, it was deemed that the idea was entirely hers and that Lomas was largely guilty of being bewitched by her and her murderous scheme.

Burrows had dispatched John Lomas previously on 24th August 1812, and now, it was the turn of Edith Morrey. He ran to work with an element of glee.

An estimated 10,000 spectators would surround the New City Gaol in Chester, all eager to catch a glimpse of Edith Morrey, a woman whom they had come to know well based on everything that they had read and gossiped about in the city’s many inns and taverns. Noticing that the curtains were removed gave them even more to be excited about.

Burrows entered his gallows with the charisma of a low-grade ringmaster. Following a few drinks to gain some extra Dutch courage, Burrows performed his latest set-piece in front of the crowd. Placing a stool above the drop, he attempted to lasso the rope over the crossbeam. Each time he failed, the crowd erupted in applause. Burrows knew exactly what he was doing. It was far from his first rodeo, and he decided to endear himself to the masses with the blackest of black comedy.

With the rope tightened to the crossbeam, he then began to play with the crowd some more. He was in his element, taking in every moment of the applause, laughter, and jeers. He was an acquired taste, but this was his moment to introduce himself to the masses, and he wanted to make sure that he made a lasting impression. Grabbing the noose, he then put his head in it and pretended to strangle himself, sticking his tongue out and shouting for mercy so that the whole of Chester could hear him.

Some loved it. To them, Burrows had now become a darling. Others hated it. In their eyes, this was the poorest of taste regardless of the crime that Edith Morrey had committed. If people were expecting any form of dignity from their newly unveiled hangman, then they would be sorely mistaken.

Either way, Samuel Burrows had now fully introduced himself to Chester. On the gallows, he was a brutish and uncompromising figure who held every possible quality required to do the job. He held a fierce commitment to the rule of law, lacked any form of guilt, and desired attention, either good or bad. He also had a strong stomach, having followed his previous career as a butcher. Despite being short in stature, he more than made up for it with his brute strength.

He loved his newfound fame, and following the execution of Edith Morrey, he continued in much the same vein. His notoriety continued even away from the gallows as he roamed the streets of Chester, drinking away any wealth that came his way.

Yet for a man so notorious, the city which he once called home has all but forgotten him. For a man who believed in the power of his celebrity, his name gathered dust in the archives…until now.

In Burrows’s mind, he was fulfilling a necessary part of Georgian justice. Whilst some would consider him to be a bogeyman, he would view himself as an anti-hero. The people of Chester may not have liked Burrows, but from his viewpoint, they needed him. He saw himself as an avenging angel with one sole aim to rid the sinners from a godly world.

For a long time, Burrows was more than prepared to live this way, but like all histories, his story is never as straightforward as that.

When I began researching the life of Samuel Burrows, I was fully prepared to tell the story of a man who thrived in his profession, but as I delved deeper, I discovered a very different man. A man who applied the noose to condemned criminals was unknowingly also applying a metaphoric noose around his own neck.

What follows in The Noose of Samuel Burrows is a grim history of Georgian Britain. Far from the regal galas that have popularised our television screens in recent years, this is a very working-class history. This is a history of criminality, desperation, and the economic tension that occurred throughout the United Kingdom during his reign as Cheshire’s notorious hangman. It reveals more about how the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of this era left many in a state of squalor, including Burrows himself. It was a period of rapid inflation that drove those who had little to begin with into a world of crime, knowing that if they were caught, then either the gallows or transportation to the colonies awaited them. Samuel Burrows would experience all the horrors of the era in some way, shape, or form.

The hangman’s burden, and indeed the burden of many, would see him slowly self-destruct over time. Whilst he was always a man with a fondness for alcohol, his habit began to spiral out of control. Drinking was a normal part of Georgian life, particularly among the working and lower classes. But Burrows began to take his drinking to the extreme. He would often be seen high on the gallows in a state of inebriation. It was a state that often saw him being picked up from the streets of Chester the night before an execution, where he was tossed into the cells of New City Gaol to sober up before executions. Yet as his drinking began to spiral out of control, it made me think. What was happening to Burrows to make him so self-destructive?

The answer comes with the devastating impact of grief and the fear of the political changes to his livelihood. Reports of Burrows’ descent into alcoholism took place following the death of his eldest son, Henry. Encouraged by his father to join the British Army, Henry joined the Subdivision of the Hundred of Broxton and soon left for the East Indies under Lord Cumbermere. Needless to say, Samuel’s pride soon turned to abject grief following news that Henry had died in service. It was a crushing blow to both Samuel and his wife, Mary.

From this point, we begin to see his steady decline into alcoholism; however, things get worse for the hardened hangman when Robert Peel’s reforms begin to threaten his livelihood. Peel’s reforms during his tenure as Home Secretary brought about the decline of the feared “Bloody Code” that previously placed over 200 crimes on the statute books, which were deemed punishable by death. Effectively, for Burrows, it meant that work would eventually become less frequent as appeals against a criminal’s conviction and punishment grew.

His youngest son, Charles, was also making news for all of the wrong reasons. Charles had turned to a world of petty crime and was caught stealing from a local merchant in Chester. Charles would be transported to Van Diemen’s Land for his crime and was fortunate not to be executed by his own father. Sentenced to seven years, it compounded even more misery on Samuel, creating tension between him and Mary, who had now lost both of her sons. For Samuel, the easy solution to mask his grief and current situation was to drink heavily to the point of addiction, which ultimately affected his liver to the point of disease and eventual death in 1835.

For a man who wanted people to know who he was during his lifetime, it seems ironic that the City of Chester has forgotten who he was. Yet, his story needs to be told once more. It reminds us that Georgian society was far from what we think we know, and through his eyes, and the eyes of those who faced him on his gallows, we can understand the period in a fuller context.

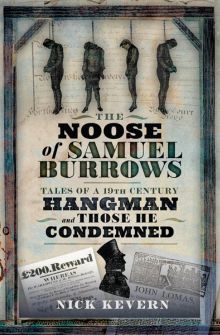

The Noose of Samuel Burrows: Tales of a 19th Century Hangman and Those He Condemned is published by Pen & Sword and is out now.