The Emperor Vitellius was not a man of whom Roman historians have ever been proud. He was one of four emperors in 69 CE, the year after the death of Nero, and was famed mainly for eating massive helpings of seafood. Since his nasty death by a thousand cuts, slowly pushed down from the Capitol hill, he has been seen mainly in art where there was need of a fat villain. But he and his family represent rather more than that, a Roman legacy to us not of literature, law or aqueducts but something more pervasive still, the birth of Western bureaucracy

They are the less than heroic heroes of Palatine, a history set inside the houses and offices of the Palatine hill, high on the edge of the Forum. It is a book about a bureaucratic family, two men in particular, a father, Lucius Vitellius and Aulus, his short-lived emperor son, also a brother and others from the chorus-line in the theatre of imperial Roman life. Many of its characters, thanks to writers over 2000 years, have been dismissed as poisoners, sexual obsessives, informers, selfish gorgers, fakes and facile toadies. But Rome, like many later cities and states for which it set the standard, lived by men and women such as these.

Palatine is a history of the big rooms seen from the small, of the top table told from the lower tables. Its events include the Roman invasion of Britain and Jewish unrest in the time of Christ but, until its final climactic year of four rivals fighting for the throne, it is a tale of peace more than war. Aulus Vitellius’s story is one of a single ruling household and of tactics for domestic times. It is a resonant story for our own times, of dimming memories of a glorious past, downwardly mobile aristocrats, sideways-moving provincials, upwardly advancing immigrants, personal excesses within the wheels of a powerful, often incomprehensible, machine.

Aulus Vitellius was a child of that machine. For four centuries Roman history had been a history of great families competing for votes and military glory, competing with gladiatorial spectacles and free food for voters, with cash and land for soldiers. At the beginning of the first century CE the Vitellii were not from one of those families but, after a century of one family rule, this was less of a disadvantage than it once had been.

Aulus’s grandfather, Publius, held a mid-level place in the family that was already supreme over all rivals. He was one of Augustus’s many procurators, part official, part servant, in the household, of which the emperor was head, the only household that mattered, a fact that the Vitellii accepted faster than others who were grander.

From his middle-ranking place in the domus Caesaris, the modest procurator, Publius Vitellius, saw his son, Lucius, become close to Antonia, daughter of Augustus’ sister, one of the women closest to the emperor. Lucius’s friendship at court with Augustus’s powerful and independent niece was his first step on the household ladder. Antonia was there to help when Lucius went on to have two sons of his own, Aulus and the second Lucius

After Aulus was born, as was the common custom, Lucius and his wife, ordered auguries to be taken. The reports were discouraging, particularly if he ever were to command an army. Lucius took careful note. He may not have himself believed in auguries but prophets, soothsayers and sibyls were everywhere in Rome and Lucius was a very practical man. Whatever his belief, Lucius acted as though the prophecies were true. His wife, breaking the imperial pattern of mothers fighting fiercely for their sons, was even more sceptical of Aulus’s prospects in life.

Aulus’s father’s skill was flattery. His own best known fascination was for eating. As Rome changed, both these skills rose in importance. For four hundred years, food and politics had been indissoluble at Rome, in bribes and on stage, in farce and as brutal force. The Forum was a food market before it was a centre for politics. Starvation was a weapon and feasting a still remembered political reward.

The earliest feasts were visible to the many, created and consumed in the open. They were political. They displayed power. Ambitious politicians, their coffers filled from eastern conquest, saw the benefit of banquets for votes at home. For the winners liberality became a signature virtue. Julius Caesar’s public banquet to mark one of his earliest offices, in 65 BCE, ensured that no one remembered again the efforts of his predecessors. At the feast to mark his third consulship in 46 BCE, two years before his assassination, he for the first time presented four different wines at every table. More than a hundred thousand dined on lampreys, eel-like delicacies gathered by supporters for whom catering became a critical political art.

Caesar left a legacy of feasting which his successors had to match and adapt and sometimes curb if the custom risked public disorder. The second emperor, Tiberius, to celebrate a military victory in almost his final act as heir to the throne, gave a public banquet on a thousand tables. Food had to be the first demand of politics. Flattery was first a way to being fed. Cooks consolidated their status as artists. Companies of cooks made their owners as rich as any men in Rome. A man called Cestius, a member of the priesthood that oversaw public banquets, built himself a pyramid fit for a minor pharaoh, still standing in Rome. Eurysaces the baker had a tomb that elaborated every part of his trade as though he were a conqueror.

The poor took whatever they could get. It was a responsibility of the emperor to ensure that the voters of Rome should at least have bread. At any time, dangerous hunger might be only a few days of failure away. The wisest of the court kept that truth close to the top of their minds. Others were more concerned with how banqueting advanced their own interests, others still with how their own behaviour might look to those who were hungry. The loaded plates, like every other part of politics, began to disappear deeper and deeper indoors.

In the age of Julius Caesar the Palatine became a site for the rich to build luxurious houses and to look down on the Forum below. Some of those clinging to power in the world that the Caesars had ended still had houses there. Many more did not, their homes belonging instead to newcomers, provincials, those who had arrived in Rome as slaves, the disrupters of old rules, the builders of empire.

The exiled poet, Ovid, was the first writer to note how Augustus had created a place on the Palatine from which to rule which would soon define ruling itself. The civic crown of oak leaves, a soldier’s decoration for saving Roman life, stood above the main entrance flanked by laurels of victory. Yellow marbled walls held red-tiled rooves. Colonnades stood against the stare of the sun, nut-trees among vines, bronze birds next to beasts spewing water into bowls. Palatine Games, theatre and gladiatorial shows, celebrated Rome’s founding emperor inside his own home.

Palatine and palace: it was a metaphor that never died. Ovid, in Rome and with a guarded irony, compared it to the home of the gods. Then, in exile, he imagined more of what had not quite arrived in the age of Augustus but was rapidly on its way. The new architecture – of place and mind – came from the needs of autocracy and from the east where autocracy, and its attendant bureaucracy, was the only way to rule.

There is much emphasis on sex in modern films about the imperial family. Neither Lucius nor Aulus Vitellius ever had a reputation for sexual excess. Both were known as uxorious in a place and time when fidelity was more a political aspiration than an individual one. But in this perilous court even Lucius could not avoid being drawn into the charge and counter charges of who was sleeping with whom. He did have one passion, it was said, for the saliva of one his own ex-slaves which he mixed with honey for his throat after a hard day at work.

Sexual charges, like charges of gluttony, were verbal weapons at court whose relationship to reality was often the least important fact about them. Any kind of oral sex – with man, woman or footwear – was especially good to use against a man whose advice needed to be brought into disrepute. In the rhetoric of the street a befouled tongue could not be trusted as a conveyor of truth.

On any day the dining tables of the Palatine made a stage. If the emperor was there, he was the star. If the emperor was not there, there had to be an understudy, a dangerous role. There were couches for all the players in sets of three, like a crescent moon around its own low table. There were some conventions on which the emperor might insist and others on which he might not. Anyone might eat and drink enough to blur fears into hopes.

The dishes themselves began with staples of the poor, the bread and wine, the eggs, always something with eggs at the start of a meal, the little vegetables, cucumber, asparagus, sweet carrots, a mullet, something stuffed, a marrow or a sow’s udder or both, apples, pears, usually apples. On some days they moved on to more elaborate luxuries, presented as in a theatrical show then taken away to be served in tiny bowls, honey-smeared nightingales, stuffed with prunes, garnished with rose petals and served in a sauce of herbs and grape juice. Sometimes they would discuss the latest dish, sometimes how luxuries were sapping the Roman spirit.

The fourth emperor, Claudius, died of mushroom poisoning, possibly brought on by his wife, and was deified in death. His successor, Nero, aged seventeen and still out to impress his mother with his wit, joked that mushrooms must be the food of the gods because Claudius had become a god by eating one. Most mushrooms were simple food. Some were greater delicacies. Green-capped, white-gilled Amanita phalloides were the most useful for promoting an elevation to Mount Olympus, their venom impervious to the heat of cooking.

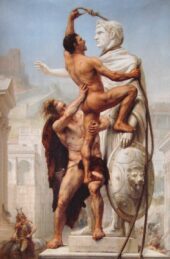

Aulus Vitellius was a party-going friend of Nero. His father had survived by flattering Caligula and Claudius. Aulus was perfect for their successor. No one, not even the most paranoid emperor, could see him as a threat. Nero’s own successor, Galba, gave him command of an army in Germany precisely because he would do nothing there but eat. He was a courtier, however, and he had juniors who saw great advantage for themselves if Aulus’s army, with Aulus himself miles away, were to win him the throne. And that was what happened. Like men in many future bureaucracies he rose to his level of incompetence – and far beyond. His first banquet as emperor became a legend. His gluttony was probably exaggerated by his failing to stay in power but it was a fame that said much about his time.

Peter Stothard is a former editor of The Times and the Times Literary Supplement and the author of Palatine: An Alternative History of the Caesars.