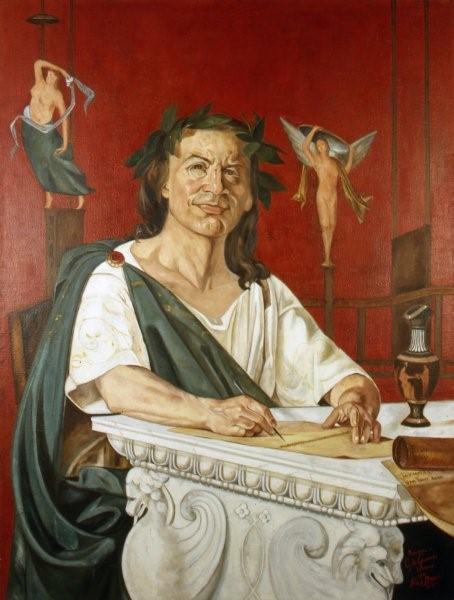

Many artists hope that they will be lasting figures in history. A few even boast that they will. But no boaster ever succeeded as well the Latin poet, Quintus Horatius Flaccus, who shouted out at the end of what he thought might be his last book ‘Non omnis moriar’, ‘I shall not entirely die’: and he never did. His poems would be read, he said, as long as priests were climbing Capitol Hill in Rome – and, though the priests may be different now, his words are the same. In many ways he was a mighty success.

This eternity did not, however, happen as he would have wished. Horace, as his English fan club came to call him, became a name on school textbooks within decades of his death. His poems were used much more to learn Latin and to write Latin than to understand and enjoy what he wrote. He knew that would happen, whether he wanted it or not, another big boast. His best known poems became those that were suitable for children. The less suitable, the more difficult, the more embarassing and personally revealing, disappeared.

Teachers over two millennia loved his pithy advice – as it seemed to them – to be free from sin and to see the sweetness in dying for one’s country. They did not like so much – or at all – his accounts of older women’s sexual habits and what those did or did not do for his libido. Everyone loved his gentle poems of idealised love. Few appreciated – maybe even fewer now – his practical comparisons between prostitutes, slaves, freed slaves and married women as sexual partners for a sunny afternoon.

Horace’s phrases like carpe diem, meaning “seize the day” or “live for the moment,” rang out loudly in philosophy and on wine labels. The words were safer when separated from his techniques for tempting partners into bed. Many other words of advice, like sapere aude, “dare to reason,” were used to fuel the advice of others much more philosophical than was he. His patriotic poems prospered, his mania not so much. The aim of my first modern biography, Horace: Poet on a Volcano, is to save the man from some of his admirers.

Some admirers of Horace have told me that a biography is impossible. It has become easy—and fashionable—to say that we know nothing about him, that the character in Horace’s poetry is a fiction, that we should be satisfied with the text and not seek the man. To argue that, it seemed to me when I began, was often to win academic points at the expense of good sense. In the thirteen hundred years between the first century BCE and the beginning of the Renaissance, only St Augustine tells his readers as much about himself as Horace does. Yes, he hides and deceives; yes too, he tells the truth. Yes, he uses the words of other writers; yes too, he chooses quotes to match what he feels himself. The role of the biographer is to negotiate the most plausible path between scepticism and credulity. Horace had an extraordinary ear for sound, an extraordinary voice, a not so extraordinary love of sex and wine, a waistline that he could be teased about. Only the most arid sceptic can deny his deeply-held gratitude to his father. Only a novelist could say anything about his mother. He was loyal to opposing causes. We know about him what he tells us—and what we can sense from close reading of everything that he tells.

Horace was born in southern Italy in 65 BCE. His father had once been enslaved. This was probably quite briefly—during civil war and in a society, unlike most others of the time, where enslavement was not necessarily permanent. But the influence of his father’s sometime slave status was strong. He was always an outsider even when he was an intimate of the great. Horace’s father made money in various trades and spent it on his son’s education, taking him from the Italian south to Rome, even acting as a slave so as to be a chaperone among the temptations of the city. Horace’s father paid for his son’s further education in Athens where, in the turmoil after Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, Horace met Brutus and other aristocrats whom he would have been unlikely otherwise to meet. By the time that the war between the parties of Caesar and his assassins was over, Horace’s father was dead. But when Horace met his new protector, Maecenas, the chief minister of Caesar’s son, Octavian, he invoked movingly the memory of his dead father, not as a poor man whom by talent he had put behind him but as the finest possible man.

By that time it is fair to call Horace a war poet. He had taken part in a vicious war and returned home to a very uncertain peace. After Caesar’s murder, Horace had left his studies in Athens to become a young officer for Brutus, leader of Caesar’s assassins, at the battle of Philippi in 42 BCE against Octavian and Mark Antony. He had witnessed the brutal clash of some 200,000 men, mass death as Romans killed Romans and family members won and lost on opposing sides. No one had seen anything like it before.

Somehow Horace escaped the battlefield, struggled back to Rome and began writing those vicious, angry poems of abuse, sometimes misogynist sexual abuse of older women, which his later admirers preferred to forget. He celebrated the end of war—while showing deep sympathy for the loser—with his much repeated lines, nunc est bibendum, “now we can drink.” He wrote poems of desperation when it seemed that war might return. He never betrayed the memory of Brutus, his first commander, even as he became a poet laureate for Octavian, Rome’s first emperor.

It is hard sometimes to like those laureate poems. But biographers of a Roman, like historians of Rome, do not have to like their subject in every respect. Horace is to me a loyal friend from the past, a writer whom other writers have long found to be a civilized companion, a poet with a distinctive voice who has encouraged the voices of others. For everyone who survives the way that he is too often portrayed at school (and some distinguished writers have not, notably Lord Byron), Horace is waiting to be a friend for life.

Horace did not claim originality of thought. He was prone to volcanic anger, but distrusted unnecessary enthusiasm. He used the beauty of language to express the commonplace, the common sense, a confident deprecation of self and a fearful pride in his country. He inspired others who wanted to negotiate difficult times in the same way—from Petrarch to John Milton, Alexander Pope to Robert Lowell.

He showed the power of technique. He was a modernist in his ancient world. The legacy that Horace most hoped for was his art of using Greek poetry to power the poetry of Rome. He was not a translator but a transformer, and he was sensitive about the difference. He was not the only—or even the first—to transform the future of literature by taking a fine knife to its past. But he was one of the most inspiring, quoted and loved.

His power almost always survives translation even when his purpose is diverted along the way. Among his translators in modern times stand presidents and prime ministers as well as poets. John Quincy Adams, Ezra Pound and Robert Frost stand beside William Gladstone, Jonathan Swift, William Wordsworth and Rudyard Kipling. In the American turmoil of the 1960s, Robert Lowell rendered Horace’s service under Brutus into his own forlorn hopes.

Horace’s art inspired some who were more forthright than he was himself. Friedrich Nietzsche, in the months before his madness took hold, put Horace at the centre of his case for the rugged virtues of Rome over Greece. Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols in 1888, source of one of the epigraphs for Horace: Poet on a Volcano, was a declaration of war on critics who thought Horace a mere copier of the Greek writers who had come before.

In Britain, a country which he saw as barbarian in his own life, Horace not only gained an English name but became a British imperialist, a genial English gentleman, a scholar of metrical technicalities, a poet whose sexuality was decorous and shrouded. His best remembered phrases were plundered for meanings far from what he wrote. My own favourite, which stands on the map at the start of my book, is his corrective to the cliché that travel is good for you: Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt; “Those who rush across the seas change their sky, not their minds.” Many others have borrowed this too—for many different reasons. Milton used it to argue that he could visit Italy without being tainted by Catholicism.

Much of Horace’s poetry and life story was adapted and removed because it did not fit what his adapters required. Horrors were buried in sweetness. Fake familiarity masked the truth of how alien his work was in so many ways. A writer cannot choose his friends. Horace has long had so many. I feel proud to be his first modern biographer and be one of them.

Peter Stothard is a former editor of The Times and The Times Literary Supplement and the author of Horace: Poet on a Volcano. His previous books include The Last Assassin, The Hunt for the Killers of Julius Caesar and Crassus, The First Tycoon.