Let’s Get Those Jerries!’: Luftwaffe Airmen and British Captors

On a hazy summer’s day in August 1940, a lone German bomber is hurtling uncontrollably towards the ground in the north-east of England; the aircraft whines in protest at the sharp hiding it has just taken from a Spitfire. As the English countryside becomes an indiscernible blur, the Luftwaffe bomber crew realise that they have no choice but to do the unthinkable: bale out over enemy territory. One by one, the five airmen slip out of their stricken aircraft and deploy their parachutes; they watch helplessly as their one ticket back to their home airbase is shredded before their very eyes.

The swaying aviators land twenty-five yards away from a humble farmhouse, but their eyes soon dart to the enormous double-barrelled shotguns being wielded by two farmers on the ground. These two farmers – who are brothers – are whispering furiously to one another about what to do next, whilst the oblivious German aircrew are unsure of how to convey that they are not a threat. As they catch sight of the brother’s wives and their young children, they know that something has to be done to break the tension between the two sides.

Eventually, they decide that smiling, clicking their heels together, outstretching their arms in a Nazi salute and crying out ‘Heil!’ will endear them to their British hosts. Unsure of how to react to this bizarre spectacle, the brothers’ wives nevertheless lead them through to the kitchen table and pull out chairs for them, plying the German airmen with the trustiest of all British libations: a steaming cup of tea. Whilst the Luftwaffe aircrew gratefully down this proffered drink, two eleven-year-old girls – Wendy Anderton and her cousin, Cathie Jones – peer curiously at the unusual sight.

Cathie’s mother later recalled on 16 August 1940 that ‘we gave them biscuits and all the cigarettes we had, and they tried by gestures to thank us.’ The initial shyness of the little girls soon gives way to doe-eyed innocence; they decide to befriend their unexpected visitors. ‘The two little girls had a grand time,’ Cathie’s mother added in amusement. ‘For over an hour, they entertained the airmen’ as they waited for local authorities to pick up the prisoners from their remote farmhouse.

Having been up in the air not even half an hour ago, the burly German aircrew were now creasing with laughter as the two little English girls joked, twirled, pranced and danced. One of the airmen tried to gift Cathie and Wendy the only items he had left on his person: ‘a metal penknife, a piece of chocolate (part of the crew’s iron ration), a German-French phrasebook and his name and address in Germany’. The Luftwaffe airmen sat back to enjoy the charming impromptu show – except for one airmen, who rocked back and forth ‘with perspiration breaking out on his brow!’

This farcical exchange highlights the strange transformative effect that a face-to-face encounter with the enemy could have during the Battle of Britain. As the Luftwaffe sought to secure aerial supremacy over the Royal Air Force in order to pave the way for Operation ‘Sealion’ – a planned amphibious German invasion of England’s south-east coast – these initially rare encounters were now a daily occurrence. Examining such unusual interactions during the summer and autumn of 1940 provides a crucial insight into how both Luftwaffe personnel and their British captors perceived one another when at their most raw and vulnerable, as well as shedding light on the extremities of character which emerged under the strains of war.

When a Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter pilot was captured on the south-east coast of England, for instance, the Hull Daily Mail reported on 23 July 1940 that ‘after being taken to a railway station by RAF personnel, the captured officer shook hands with and saluted the WAAF who drove him away.’ The Portsmouth Evening News added that the Luftwaffe officer ‘paid the same courtesies to the officer in charge of the escort party.’ That same month, however, some of the Luftwaffe prisoners of war being transferred to Canada were allegedly highly unpleasant to the British officers on the transport ships.

One of the officers claimed that the German army and navy personnel ‘were little trouble, but the Nazi airmen were “an arrogant lot [who] called us swine nearly every chance they could.”’ Some of the younger airmen aboard the voyage, too, ‘affected swashbuckling tactics and tore to shreds their gas-masks which were to have been returned to England.’ Thus, although the tentative relationship between downed Luftwaffe airmen and their British captors was largely respectful, they were always one ugly moment away from remembering what was truly at stake during the Battle of Britain.

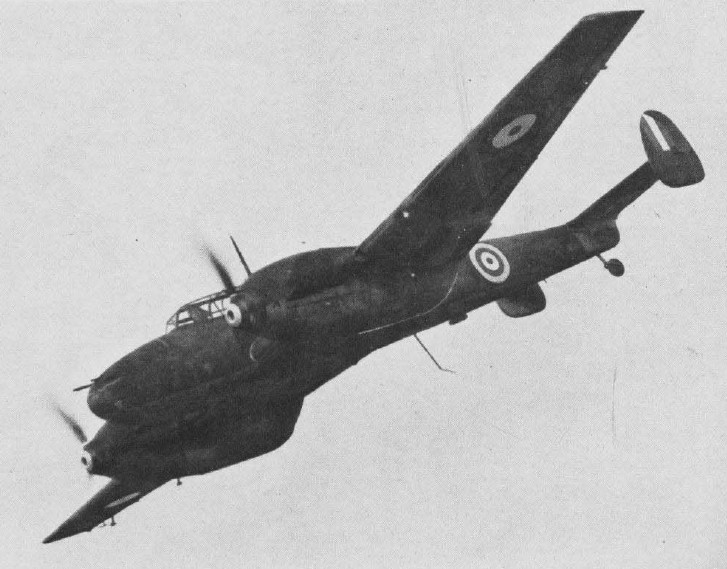

Given the wartime tensions, language barriers, and searing adrenaline that swirled around them, however, it was natural to be cautious of the other’s intentions. As fate unceremoniously thrust them into the roles of captor and captive, apprehending downed German airmen required great courage and composure from the British public. A rather amusing tale was told by the Edinburgh Evening News on 13 July 1940 of a Mr Brown who had disarmed a Heinkel He 111 bomber crew using a toy pistol. After crying out, ‘let’s get those Jerries!’, a nearby landlord had quickly:

“…jumped over a hedge with his hand in his back pocket as though he had a revolver there, and Mr Brown followed him with a toy pistol in his hand. They shouted: “come on, give us those guns!” There were five occupants in the ‘plane, one of whom, the gunner, was dead, and another, the pilot, seriously wounded. The uninjured Germans handed over their revolvers and were covered by their own weapons for a time.”

On 24 August 1940, the Daily Record printed a similarly heroic story of ‘Mr. Lewis Frith, the gamekeeper who, “armed” with only a pitchfork and accompanied by his two dogs, “held” the crew of four of a German Dornier [Do 17] which crashed in south-east England yesterday.’ Frith tapped the pocket of one German officer ‘expecting to find a revolver, and he at once handed me his automatic. He said it was a souvenir from the Spanish [Civil] War.’ But Frith was surprised to be offered a souvenir of his own from the downed Luftwaffe aircrew:

“I was joined by an Army officer and he took revolvers from the other Germans. They could all speak English and asked if they were in the heart of England. They all had supplies of peppermints and chocolates – and they insisted on offering us some.”

As heartfelt as this gesture may have been from the Dornier crew, it was also in the Luftwaffe airmen’s best interests to be as non-threatening as possible to their captors. The idea that the British would kill Luftwaffe airmen if they landed upon the island was a common misconception expressed by the downed Germans. According to the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette on 20 August 1940:

“German airmen who have been brought down and rescued clearly indicate by their attitude that it has been drilled into them that if they are captured, they will either have their throats cut or be shot. In one northern hospital, Germans who had been wounded by our Spitfires or Hurricanes in dogfights were even afraid that the anaesthetic given was a poison, and when they found that they were getting every medical attention and good feeding, they were amazed and expressed their gratitude.”

It is possible, of course, that British wartime press was attempting to emphasise the barbaric nature of the Nazi regime by frequently reporting the story that the German airmen expected to be mercilessly slaughtered by the islanders. Nevertheless, this phenomenon was also confirmed by the historian Kenneth Wakefield, who interviewed Hauptmann Helmutt Brandt – a former He 111 bomber pilot shot down over Bath during the Battle of Britain – after the war:

“A hostile crowd of local people had gathered around him by now and remarks were being made by those present that he had been bombing women and children. He remembered replying that he was only doing his duty in the same way bomber crews of the RAF were doing theirs over Germany. A member of the Home Guard arrived carrying a rifle and Brandt thought he was about to be shot. It was quickly explained to him that the British did not shoot prisoners of war.”

It was likely, then, that the Luftwaffe airmen were briefed that they would be killed on sight by the British in order to scare them into getting back to Reich territory by any means possible and at any cost. However, it was not an entirely far-fetched notion that members of the Home Guard (formerly the Local Defence Volunteers) may potentially be trigger-happy, considering that they were sometimes enough of a danger to their own side. On 27 August 1940, the Daily Mirror reported that:

“A reward of £5 for every German parachutist captured alive by his men has been offered by the officer commanding Newgate Street (Herts) unit of the Home Guard, Mr. Menzies Sharpe. He said yesterday that he has done this to minimise the danger of Home Guards, through overzealousness, shooting at British airmen who have been forced to bale out. Major Sir Jocelyn Lucas, M.P., is to ask the Air Minister in the House of Commons to grant some reward for live parachutists to remove this danger to RAF airmen.”

Whether an airman was British or German, to be on the other end of the Home Guard’s overexcitability was not a pleasant experience. On 18 August 1940 – more commonly known as the ‘Hardest Day’, with both the RAF’s Fighter Command and the Luftwaffe taking their heaviest collective losses in one day – the Do 17 bomber pilot Hauptmann Rudolf Lamberty was shot down over RAF Biggin Hill. ‘I got out desperately,’ he recalled, ‘touching the red hot metal with my hands’ and irrevocably scarring them in the process. But, as he landed and tried hard not to collapse:

“I remember seeing some very excited Home Guard men with shotguns etc. Excited and yet also a bit fearful. They pointed their guns at me. I met my Staffelkapitän [‘Squadron Captain’] – he did some arguing with them to make them put their guns away. He was severely burnt (more than me), the skin was hanging down from his face and hands, as he stood there, arguing with them. I was busily engaged in putting out the fire on both my sleeves – patting at them.”

Yet Lamberty also recalled the kind treatment he received from his British captors, noting that ‘I asked them to put a cigarette in my mouth and light it, as I couldn’t. They did it. There was astonishment because they were English cigarettes – I had bought them in Guernsey a few days previously.’ He added that ‘he couldn’t eat at all, as my mouth was burned inside. They thought it was because I didn’t like the food and brought me some other types of food.’

In other cases, the Anglo-German interactions became more strained due to the spiteful retaliation and lack of remorse occasionally displayed by some captured Luftwaffe airmen. William David, a flight commander with No. 213 Squadron, remembered a particularly nasty incident when German Stukas had bombed RAF Tangmere ‘and caught the whole WAAF contingent changing from one watch to another and they killed a lot of girls, which really upset people.’ He alleged that ‘one of the Germans [prisoners of war] was seen to smirk. And the RAF commander hit him very hard to stop him laughing.’

But, unless they clearly stepped out of line, the German airmen were generally treated compassionately and even kindly by the island’s civilians. This sometimes proved contentious among the British Army, who had witnessed the full horrors of what the Luftwaffe could achieve on the ground in France. During the Battle of Britain, a sardonic cartoon appeared in an Army regimental broadsheet which depicted a subaltern being sentenced by his Commanding Officer to thirty days’ confinement to quarters “because he, while acting as Orderley Officer on the date in question, failed to offer the captured German pilot a cup of tea”!

The default interaction between the RAF and the Luftwaffe, on the other hand, tended to be one of mutual respect and understanding, as exemplified by the great pains taken by the British when burying fallen German airmen with full military honours. As the dead crew of a Junkers Ju 88 bomber were being buried in August 1940, ‘floral tributes were sent by the commanding-officer, officers, N.C.O.s and men of an R.A.F. station. A large number of people attended the funeral, which was conducted by an Air Force chaplain assisted by the local clergyman.’ After all, even though their Luftwaffe counterparts had been fighting on the orders of a murderous tyrant, the RAF personnel recognised an airman’s ultimate sacrifice for his country when they saw it.

These extraordinary stories, then, illustrate the full human complexity of wartime encounters between downed Luftwaffe airmen and their British captors; they demonstrate that the distinction between mortal enemy and fellow human was not always as black-and-white as the wartime press would have each side believe. At their worst, explosive altercations further hardened one another’s hearts; at their best, more civilised interactions constituted touching moments of humanity and humility. Though fleeting, these remarkable encounters serve as a powerful reminder that even amid life-and-death struggles, courtesy and decency can still prevail.

Victoria Taylor is an aviation historian, broadcaster and writer whose first book, Eagle Days: Life and Death for the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain, was published in May 2025.