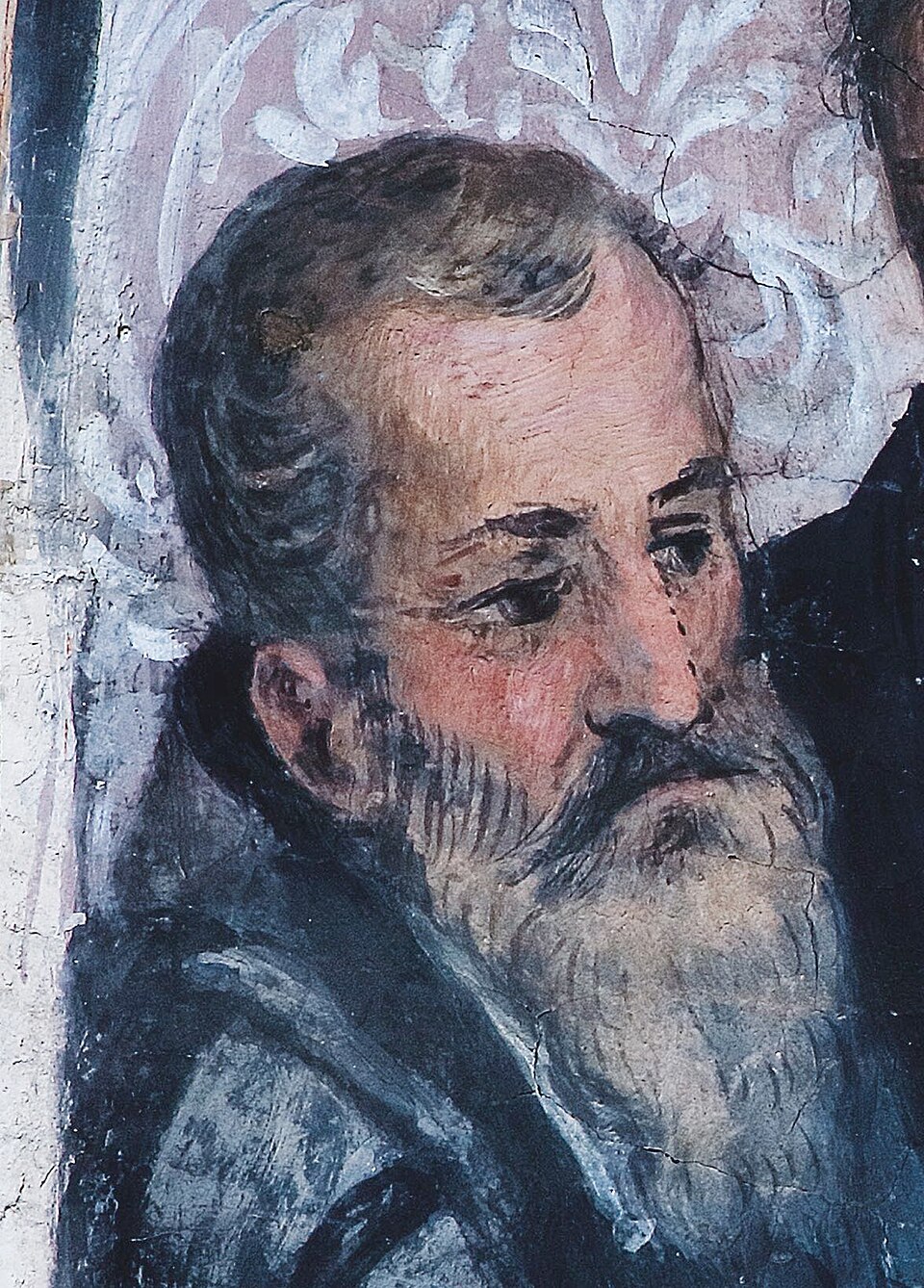

My short story City of the Damned traces the years of Hugh O’Neill’s life from his defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601 to his exile in Rome surrounded by spies, plots, and the threat of poison. This is the man who came closest to ending English rule in Ireland and almost bankrupted the treasury of Elizabeth I in the Nine Years War.

Hugh O’Neill is an emblematic figure in Irish history, yet as a person he remains unknown. In part this is because, as Sean O’Faolain pointed out in the most recent full-length biography (published in 1942) he does not conform to the stereotype of the Irish nationalist rebel. In his play ‘Making History,’ Brian Friel has described O’Neill as being ‘too English for the Irish and too Irish for the English.’ Described by Henry IV of France as ‘the third great soldier of his age’, O’Neill was a charismatic and shrewd diplomat and a skilled military strategist. Yet in the end he was defeated by his inability to reconcile the irreconcilable – being an autonomous leader under the crown and being a traditional Gaelic ruler on his own terms.

When Elizabeth I became Queen in 1558, the central plank of William Cecil’s strategy to secure her throne was the creation of a unified and protestant British Isles. To that end, he needed to complete the pacification of Ireland and bring Scotland into a close and binding relationship with England. Over time the challenges he faced were personified by Mary Queen of Scots and Hugh O’ Neil, Earl of Tyrone, known to posterity as ‘The Great Earl.’

His beginnings were not promising. The O’Neill clan had been the dominant political force in Tyrone, and more broadly in Ulster for generations, yet the word ‘internecine’ could have been created to describe their fratricidal politics. Hugh O’Neill’s father, Mathew, was murdered by his Uncle Shane in a dispute over the inheritance of the Earl of Tyrone title. His older brother Brian was murdered by a cousin and ally of Shane, Turlough Luineach, and Shane himself was murdered by the MacDonnells of Scotland with the probable collusion of Lord Deputy Sidney. This left the way clear for Turlough Luineach to assume the traditional title of ‘The O’Neill’. So far so simple, but the net result of all this was that by 1567, aged 17, Hugh O’Neill was the theoretical claimant to a disputed title with no power base and little chance of making good on that claim.

In the world of sixteenth century Irish politics nothing was static. The loyalty of Turlough Luineach to the crown was at best erratic and Hugh O’Neill was a useful political counterweight. Following the assassination of his father, the young O’Neill had been fostered with the English Hovenden family in north County Dublin, and he had grown up speaking English and accustomed to the ways of the court in Dublin.

In late 1567, he accompanied Lord Deputy Sidney to London where he was presented at court. O’Neill was handsome and intelligent. He charmed Elizabeth and started building the network of contacts that was to stand him in such good stead. Among the courtiers who surrounded Elizabeth, O’Neill developed particularly close connections with the Earl of Leicester, the Earl of Kildare and Elizabeth’s own cousin, the Earl of Ormonde. This charm offensive worked and O’Neill returned to Ireland with a grant of land in Oneilland and, at the Dublin parliament of 1569, he was formally installed as Baron Dungannon, the subsidiary title of the Earl of Tyrone.

O’Neill was a skilled diplomat and strategist, but he was also ruthless and driven by the need to secure what he saw as his just rights. Marriage was an important means of dynastic advancement and, around this time, O’Neill married Katherine, the daughter of Sir Brian McPhelim O’Neill of Clandeboye. Sir Brian was an ally of the English and had been knighted for his help in the wars against Shane O’Neill. It was a good strategic alliance. However, when Sir Brian went to war with the Earl of Essex over plans for the plantation of Antrim, O’Neill stood by Essex. In 1564, Essex invited Sir Brian to a parley in Belfast during which 200 of his followers were killed. When Sir Brian, his wife and nephew were arrested and taken to Dublin to be hanged, there was no protest from O’Neill. Instead, he hastily organised the annulment of his marriage to Katherine and, by the end of the year, he was married to Siobhan O’Donnell, daughter of Sir Hugh McManus O’Donnell, Lord of Tyrconnell.

The O’Neills of Tyrone and the O’Donnells of Donegal had been sworn enemies for generations, so what was behind this sudden shift? Much has been made of O’Neill’s great skill in developing a network of alliances and relationships, but, in reality, it is impossible not to see the hand of O’Neill’s mother, Siobhan Maguire, in building these key strategic alliances. After the murder of O’Neill’s father, Siobhan married Henry O’Neill of the Fews in County Armagh, who at a time of greatest danger became one of O’Neill’s staunchest and most courageous defenders. Her third marriage was to Sir Eoin O’Gallagher, chief adviser to the O’Donnell’s of Donegal. Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell would later be brothers in arms for the duration of the Nine Years War.

O’Neill continued his two-handed strategy of ostentatious loyalty to the crown while re-establishing his relations with the most prominent Gaelic lords. However, where diplomacy and charm did not work, he was not averse to resorting to murder. In 1590, he ordered the execution of his cousin and rival Hugh Gavelagh O’Neill, son of the late unlamented Shane and, when Phelim McTurlough O’Neill had the temerity to stand in his way, he was also quietly eliminated. O’Neill played a significant part in the suppression of the Second Desmond Rebellion and, in 1585, he was finally rewarded with the restoration of the title of Earl of Tyrone.

It is, however, one thing to acquire a title: it is something else to hold on to it. O’Neill now set about making his position impregnable. As Earl of Tyrone, he was entitled to recruit a troop of 200 men. The men were armed and trained in modern military tactics by officers returned from fighting on the continent. By regularly replacing the initial 200 with new recruits, he gradually built up a formidable fighting force.

The supply of ammunition was a perennial problem, but here O’Neill found an ingenious solution. While building his new castle in Dungannon, O’Neill needed lead for the roof, large quantities of which were siphoned off for the production of bullets. No one seemed to question how such a comparatively small castle needed such a vast amount of lead. He established arms dumps across his territory and built a network of roads and a parallel network of spies. The problem for O’Neill was that the more powerful he became, the less the English trusted him.

A decisive moment was fast approaching. In 1588, a violent storm in the English Channel scattered the mighty Spanish Armada which found itself sailing before the storm onto the rocky shores of Ireland. This was the nightmare scenario that the English had long dreaded: a Spanish army in Ireland leading an Irish rebellion. Martial law was declared and death was the punishment for anyone who assisted survivors.

An estimated 20 Armada ships landed along the west coast of Ireland. Was this the opportunity for O’Neill to raise the flag of revolt? On 12 September 1588, the Trinidad Valencera sank in rough seas on the shores of Kinnagoe Bay in County Donegal. Four hundred men made it ashore. O’Neill’s troop of 200 men, under the command of his closest associates, the Hovenden brothers, was told to rendez-vous with the O’Donnells and report to Major Kelly in Inishowen to ‘deal with the situation.’ A small number of the survivors were held for ransom, and the remainder were slaughtered and buried in two, now unmarked, mass graves. O’Neill had passed the test and stayed loyal: pragmatic politics had triumphed over principle. An estimated 6,000 soldiers and sailors from the Armada drowned in Irish waters and, of those who made it ashore, an estimated 1,500 were executed in what would, nowadays, be considered a war crime.

By the 1590s Hugh O’Neill was the richest, most powerful man in Ireland with an estimated income of £80,000 per annum. Though described by some as ‘the Queen’s O’Neill’, things were changing as the Dublin administration pursued a policy of encroaching on the rights of Gaelic Lords by the imposition of English law, sheriffs, and garrisons. O’Neill’s position as an autonomous ruler was under threat. The execution of key O’Neill allies led to the development of a proxy war between 1593 and 1595 during which his allies harassed the English forces while he maintained a loyal distance.

This proxy war exploded into all-out conflict in 1595 when, with superior arms and better strategy, O’Neill decisively defeated an army led by his brother-in-law Sir Henry Bagenal. O’Neill had caused a major scandal four years previously by seducing and eloping with Bagenal’s sister Mabel.

During this period O’Neill consolidated his position by enforcing his authority over neighbouring territories and importing a steady flow of weapons and gunpowder from Scotland, a trade to which King James, for reasons of his own, turned a blind eye. In a letter to James, Elizabeth complained that O’Neill was receiving more aid from Scotland than from Spain. Meanwhile, O’Neill continued negotiations with Spain in hopes of a Spanish invasion that would tip the military balance in his favour.

When O’Neill defeated an even larger English army at the Battle of the Yellow Ford on 14 August 1598, in which Sir Henry Bagenal was killed, O’Neill was unstoppable. The road to Dublin lay open and O’Neill’s forces were able to march unchallenged from one end of Ireland to the other. The end of English power in Ireland was in sight. Yet O’Neill hesitated. While previously reluctant allies flocked to his banner, O’Neill still hoped for a negotiated settlement. Even Burghley wrote to O’Neill saying that if their differences could be resolved he would ‘welcome O’Neill back to court and shake his hand.’

Such was Elizabeth’s determination to bring O’Neill to heel that, in 1599, she sent her favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Essex, to lead the largest army sent into Ireland. Essex was arrogant and incompetent and allowed himself to be cajoled by O’Neill into agreeing a truce. This so infuriated Elizabeth that it unleashed the chain of events that brought Essex to the block.

Two things then happened which determined the course of events. On 24 February 1600, Lord Mountjoy arrived in Ireland as Lord Deputy. His scorched-earth policy in Ulster combined with the building of forts on the shores of Lough Foyle threatened O’Neill in a pincer movement that forced him back onto the defensive.

On 21 September 1601, a fleet of 28 Spanish ships arrived in Ireland with approximately 4,000 fighting men on board. Unfortunately, they arrived in Kinsale in County Cork at the opposite end of the country from O’Neill’s base in Tyrone. Mountjoy immediately marched south to besiege the town of Kinsale while O’Neill and O’Donnell had to rally their forces and coordinate a 300-mile march, in winter conditions, to link up with the Spaniards. Exhaustion, bad communication and bad decisions all contributed to the debacle that ensued. Instead of following O’Neill’s advice to sit out the siege and let the English die of starvation and disease, Hugh O’Donnell insisted on a direct attack. A surprise counterattack by the English cavalry was decisive and the combined forces of O’Neill and O’Donnell were scattered.

While the march south had been something of a triumphant progress, the return north in disarray was a different story. Erstwhile allies fell away and some directly switched to the winning side and attacked O’Neill’s retreating army. But Hugh O’Neill was not so easily broken. Although he spent the next two years on the run in the forests of Glenconkyne, no one could be persuaded to betray him. Hugh O’Neill finally submitted and accepted the terms of the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603. On the day of his submission, he was unaware that Elizabeth had died three days previously.

To the consternation of many who had fought against him, O’Neill retained his title of Earl and most of his lands, though he had to accept English laws and jurisdiction. England needed peace as the country was on the brink of bankruptcy. The war in Ireland had cost £2 million, twenty times what had been spent on defeating the Spanish Armada and England was still embroiled in a war in the Spanish Netherlands. Accepting Hugh O’Neill back into favour was the price of a peaceful succession for King James. In June 1603, Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, travelled to London with Lord Mountjoy to make his formal submission to the King.

Meanwhile, there were many in the Dublin administration who had fought O’Neill for years and were deeply resentful of this favourable treatment. In the coming years, the enforcement of English laws led to a series of protracted legal disputes which were exploited by the new Lord Deputy, Sir Arthur Chichester, to undermine O’Neill’s position. In 1607 O’Neill was summoned to London for the examination of his dispute with O’Cahan, one of his former allies. Fearing arrest, on 4 September 1607, Hugh O’Neill, the Maguire, Rory O’Donnell and one hundred of their followers set sail from Rathmullan in what became known as the ‘Flight of the Earls.’ It was the end of the old Gaelic world in Ireland.