Harold Godwinson – The Greatest King We Never Had?

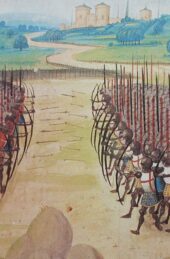

My debut historical adventure series, The Wolf of Kings, focuses on the rebellions that took place post-Norman Invasion. Since these uprisings occurred after 1066, King Harold Godwinson doesn’t feature that predominantly (spoiler-alert: he doesn’t make it). However, while researching the period, and learning how the cultural and economic landscape of 11th-Century England changed when William the Bastard took power, it had me thinking; what might have happened if the Battle of Senlac Hill had gone differently? How would England (and its neighbours) have fared had Harold won? And what might have been the wider implications for Europe, and even the rest of the World?

A good place to begin with such speculation might be to examine what kind of man Harold was. Certainly, the majority of the Saxon population of England would have seen him as the rightful heir to the throne, he was after all a powerful and well-established earl, and for the most part scholars of the period were complimentary. Orderic Vitalis describes him as ‘very tall and handsome, remarkable for his physical strength, his courage and eloquence, his ready jests and acts of valour…’ All the qualities for a strong and benevolent king, even by today’s standards. But was that the whole truth?

In reality, Harold was a pretty ruthless and ambitious man, from a very ruthless and ambitious dynasty. His father, Earl Godwin had raised his family with the express ambition of seizing the levers of state. Harold’s sister had been married to the previous king, Edward the Confessor, and he and his brothers established as earls in every earldom. When his brother Tostig was faced with the prospect of rebellion in his earldom of Northumbria, rather than support him Harold had him replaced with local magnates Edwin and Morcar, and married their sister to consolidate a union between them. This meant abandoning his previous wife (albeit wedded under pagan law) and the mother of his six children for political expediency. It’s also worth pointing out his new wife was widowed as a direct result of Harold’s violent military campaign in Wales a few years earlier. A campaign that so ravaged the Welsh territories they murdered their own king just to appease Harold, and presented him with his head.

But does this in fact make Harold a ruthless king? Judging him by today’s standards he certainly appears as such, but through an 11th Century lens – very much a time of might makes right – his callous actions may well have been the only way for him to survive. It is hard to guess whether his rule would have been a successful one, after all he was only on the throne for nine months and never had long enough to consolidate his reign. Would he have harboured wider ambitions to conquer Scotland and Ireland as King William did? We’ll never know, but it’s certainly worth noting that without the Norman invasion, England would most certainly have remained secure for a significant period after Harold took the throne.

Internally, England’s earldoms were stabilised by the fact Harold and his brothers, Leofwine and Gyrth, controlled the south, while Mercia and Northumberland were held by his brothers-in law. By defeating Harald Hardrada he had neutralised any threat from Norway, and King Sweyn of Denmark was already a friend and ally. Harold was also friendly with Diarmait, High King of Ireland, and Malcolm Canmore of Scotland was never powerful enough to offer any real threat to the united earldoms of England, other than the odd raid. It is difficult to speculate on the long-term ambitions Harold might have held, but there is little evidence that he sought to conquer and unite the rest of the British Isles – particularly when you consider that after his utter trouncing of the Welsh, he allowed them to continue governing themselves. Had he defeated William at Hastings, the threat from Frankia would likewise have been eliminated – certainly for his lifetime. Harold would have inherited a kingdom free from external strife, but his problems would not have been entirely over.

Unfortunately, despite the alliances that would have consolidated his reign post-1066, Harold had orchestrated problems along his own line of succession. His eldest son, Godwin, would have been his natural heir. Godwin’s brothers, Magnus and Edmund, could also have been given earldoms to consolidate Godwin’s hold on his father’s kingdom (although that in itself might have caused strife with the sons of Gyrth and Leofwine, had they wanted to pass on those earldoms to their own issue). However, Harold had married again, and by many accounts his new wife, Ealdgyth (Alditha in my novels) was with child within the year. Had he lived longer there is every chance Harold would have sired more heirs by Ealdgyth, all with claims to land and title. Had either Edwin or Morcar outlived Harold, they would immediately have supported their nephew’s claim to the throne over Godwin’s. Such a claim may also have been supported by the clergy, since Godwin was conceived within a handfast marriage, and may not have been considered the rightful ruler of England under God. The consequent witenagemot to decide who took the crown would have been a fractious one, with the thegns and magnates of north and south split on their decision. Everything Harold had done to unite England would immediately have been destabilised, throwing England into another period of upheaval, rebellion and war.

But what would the legacy of a Godwinson reign have meant for his neighbours across the Channel? William himself managed to unite the country by a ruthless campaign of subjugation, but his origins in France, along with the establishment of a Norman ruling class, directly led to the Anglo-French conflicts that would affect both countries for centuries. Norman-English kings held hereditary lands in France, which resulted in a catalogue of wars due to disputes over territory, from the Vexin Wars of the early 12th-Century right up to the end of the Hundred Years War in 1453, and possibly beyond. King Harold had no hereditary claims on French territories. Had he ruled beyond 1066 the perpetual strife between England and France could well have been avoided, though it would be churlish to suggest they would never have gone to war. England and France would have remained contentious neighbours, but with no successional links, neither would have been able to lay claim to the other’s lands.

The fact that Frankish lords controlled the country’s wealth and territory at the expense of the Saxon populace, also begs the question of whether England would have become a more egalitarian place had the Normans not taken over? Certainly, the echoes of the class divide William perpetuated are still heard a thousand years later, but would England have been a haven of equality had he never won victory at Hastings? Well… unlikely.

When King William took control of England in 1066 an estimated 10% of the population were slaves, with the rest of the populace stratified along the lines of Ealdorman, Thegn and Ceorl. The country was already deeply divided by class structures, and it is unlikely that would have changed during a Godwinson kingship. Indeed, one of the first things William did was to put a heavy tax on the ownership of thralls, thus effectively abolishing their use. Whether this improved their lot is questionable, but it does beg the question of ‘What else did the Normans ever do for us?’

Unfortunately, this seemingly good deed was soon cancelled out by William’s last desperate act to curb rebellion in his fledgling kingdom. It was an act that would irrevocably damage the north of England and retard its development for decades, if not longer. The Harrying of the North, during which thousands were killed in the slaughter and consequent famine (Orderic Vitalis mentions 100,000, though that is most likely an exaggeration), effectively destroyed England’s northern territories. Again, this act of wanton vandalism had repercussions that arguably lasted centuries after the deed was done, and deepened the divide between north and south – a divide that would likely have been eliminated by dynastic union under Harold’s reign.

What other implications would a Godwinson rule have had for the wider continent, and indeed the world? It is worth pointing out here that Harold’s lineage was Danish in origin. Though his father Godwin’s background is disputed, he most definitely married into a Danish noble line (his wife Gytha was the daughter of an earl and related to Cnut, the last Danish king of England). Harold’s links with Scandinavia were much stronger than with the rest of continental Europe, and France in particular. Under King Harold’s rule, those links would only have grown stronger, while those with France (perpetuated under Edward the Confessor) most likely reduced. Without the constant territorial disputes with France it is unlikely England (and Britain) would have been under the constant war-footing that led to it evolving as a dominant military power over the centuries. Though it is impossible to speculate with any accuracy, it is unlikely England’s colonial ambitions would have developed in quite the same way – which would have had much wider repercussions. Had William not conquered England, the British Empire would certainly have looked much different, along with the social, economic and political evolution of the entire world.

What we do know, is that English society would have been transformed had King Harold been victor, and by association, the rest of history. But for that fateful day, the cultural and physical landscape of western civilization would have been completely altered, from the food we eat and the clothes we wear, to the language we speak and what we call ourselves (how very different we’d be if we were called Wulfgar, Stannhilde and Ethelfrith, rather than Alan, Brian and Richard). The Battle of Hastings truly was a ‘sliding doors’ moment in world history. Whether a victory for Harold would have changed it for the better, we’ll never know.

Richard Cullen is the author of The Wolf of Kings series, his latest book in the series is Winter Warrior.