The ‘miracle of Dunkirk’ is lauded in British history and folklore as a victory of human endeavor, celebrated each year with a profusion of TV documentary veteran accounts and memorial services. German soldiers constantly referred to the wunder or miracle of reaching Dunkirk in wartime letters back home. There the resemblance ends. For the British it was a miracle of survival and deliverance, for the Germans it was one of achievement. They had reached the sea in May 1940 in less weeks than it took years for their fathers not to succeed in 1914-18.

The panzer ‘Halt Order’ called by Hitler on 24th May 1940 is generally accepted in many accounts as the reason why Operation Dynamo succeeded. However, only one of the three days the panzers halted coincided with the nine days it took to evacuate. The French had already fought off the only panzer division attack against the port from the west, on the day the order was issued. A terrain walk around the Dunkirk perimeter reveals just how unsuited the entire area is for armored operations. The port lays within a concentric system of canals and is crisscrossed by a herring bone pattern of drainage ditches. Allied narratives reveal the extent to which all the low-lying countryside about was flooded. Whatever the direction of the German advance, at least five to six canal lines have to be crossed, to reach the port. It therefore made eminent sense for the tanks to halt. No contemporary British veteran accounts of the evacuation mention any fear that panzers might be approaching the beaches.

If the panzers were unable to capture Dunkirk, what was the role of the Luftwaffe in preventing escape? Unfortunately, most of the relevant Luftwaffe records were destroyed by allied bombing later in the war. Surviving documents, which include intelligence reports and von Richthofen’s surviving Fliegerkorps VIII Diary suggest that despite Göring’s promise to the Führer to eliminate the pocket, it was not followed by an immediate supreme Luftwaffe air effort. Reports and returns after the 24th May, when assurance was given, indicate many other targets, inland and along the coast, were attacked instead. The weather emerges as the primary area of concern within the documents. Only 2½ of the nine-day siege of the Dunkirk perimeter offered sufficiently clear conditions to mount heavy raids.

Another relative unknown, was the effectiveness of RAF low level bombing and strafing attacks on overly sensitive German troops. Virtually every veteran German account includes complaints about the RAF, who appeared to be seriously denting the prevailing Luftwaffe air umbrella. Unit after-action accounts are permeated with references to vehicles and men lost here and there due to unexpected air attacks. Many German commanders mention the frequency of headquarter location moves due to RAF air attacks. Apparently the ‘Brylcream boys’ did better than the British Dunkirk veterans ever admitted, mainly because they were high and out of view.

British troops wait on the beach of Dunkirk.

Dunkirk, like the battle for Arnhem in September 1944, also revered by the British as an epic action against all odds, was likewise regarded by the Germans as simply a sideshow, a subordinate front. Both were pockets of British resistance, contained in isolation, which needed to be mopped up. Dunkirk in 1940 was the proverbial sign post, pointing German soldiers to Paris and victory over France.

Because it evolved as a sideshow, enveloped by only ten German divisions, there are very few surviving German contemporary ‘voices’ left to tell us about Dunkirk. All ten divisions committed were subsequently destroyed in Russia. Few veterans who had fought at Dunkirk returned. German voices at Dunkirk come from personal narratives, primarily war correspondent accounts published in 1941. By then the French campaign had already been eclipsed by the greater crisis in Russia. There are, however, numerous Feldpost letters home, diaries and unit after action reports to investigate. These have been extensively trawled to include all the surviving division and corps, and Luftwaffe unit records relating to the fighting around the perimeter.

The Belgian capitulation of the 28th May was possibly the greatest crisis moment for the success of Operation Dynamo. The sheer scale of the capitulation, 22 divisions laying down their arms at one moment, filling the roads with thousands of Belgian troops and masses of civilian refugees, all going they were not sure where, seriously impeded German operations. The best they could do was hastily form motorized units with captured enemy vehicles and head for the coast, while the mass of the German infantry advance was skillfully screened off by the retiring 2nd British Corps of the BEF. An opportunity to roll up the evacuation beaches from the east, before the mass of the fighting elements of BEF arrived, was thereby missed.

The real climax of the battle for Dunkirk was three days between 31st May to 1st June when the bulk of the BEF’s fighting divisions were taken off, the surviving veterans, under the noses of the Germans. This is the story Dünkirchen tells, the unseen narrative from the German perspective. It is one that surprisingly, after eighty years have passed, has never been satisfactorily told. Rarely has any narrative sought to portray the battle from the perspective of ordinary German soldiers. In so doing a plethora of information, contrary to many of the popular myths about the ‘miracle of Dunkirk,’ has been uncovered.

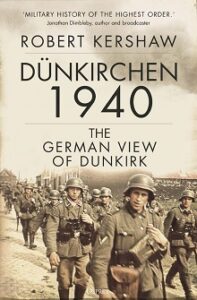

Robert Kershaw is the author of Dünkirchen 1940: The German View of Dunkirk, published by Osprey.