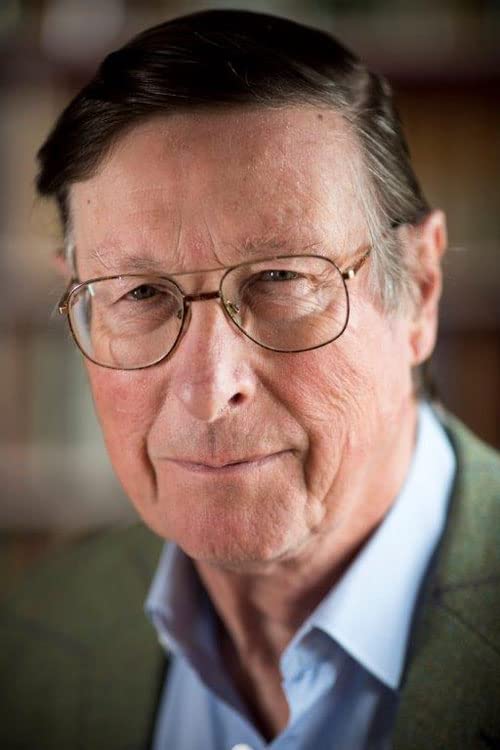

Trial by Battle: Max Hastings Interviewed

Max, it wasn’t long since we discussed your last book Operation Biting and you’ve already produced this fantastic book, Sword. How do you do it?

I’m an old man in a hurry, but there’s lots of things I still want to say about war and about soldiers. I’m now in my 80th year and you can’t expect to go on forever. I feel this huge sense of excitement when I think of things that one wants to say and one just wants to get them down on paper and get them out there before something terrible happens to me. I also love doing it. I don’t want to play golf. What I really like doing is reading and writing about the history of war.

And why Sword Beach, Max?

I was fascinated by this business of the men who landed there being virgin soldiers, that most of them had done nothing except train and exercise and become incredibly bored in England for four years between Dunkirk and D-Day. And when they landed, this was the first time they’d heard a shot fired in anger.

What was very different from the First World War, although of course it was a bloodbath on the Western Front, was that there was a convention that, when units were newly arrived in Flanders or in France, they be sent to a quiet sector of the front for a few days or weeks to experience the least ghastly side of war before they were plunged to its extremities.

Now what happened on Sword Beach and on D-Day was that the British Third Division and the accompanying 29th Armoured Division were thrust from four years of training in England suddenly into the whitest heat of war and most of them found this an extraordinary, pretty traumatic experience and who can blame them?

How did they get on?

One story that’s stuck in my mind, and I’ve told it in the book, was of a commando NCO who suddenly found himself confronted a mile or two inland from Sword, late on the morning of 6 June, by a screaming prisoner whom he had shot. This was a teenager from Graz in Austria, as the unit’s interpreter discovered.

The commando said to the interpreter, ‘What’s the German word for ‘sorry’?’ This commando kept saying ‘Versaillung, Versaillung!’ to the screaming teenage German prisoner. The commando turned to the interpreter and he said ‘Can you explain to him that I’ve never shot anybody before?’

To me, these things are fascinating, that it doesn’t come naturally, shooting people. It’s something that most people find very traumatic. You can have all the live fire exercises in the world and nothing prepares you for the sight of men, hideously maimed, suddenly, literally blown apart before your eyes. What is really tough is to keep going in those circumstances.

You’ve also written about the Merville Battery.

I hope I’ve told it more originally than most – the storming of the Merville Battery by the 6th Airborne Division by 9 Para. Now this was a shambles of a parachute drop in the middle of the night before D-Day and the Colonel in charge of 9 Para suddenly found himself with only about a quarter of the strength of the battalion expected to take out this German battery. They charged the battery. They took heavy casualties. They lost about half the men who charged the battery, but they did take it. Now that was one action in the early hours of D-Day.

But, a few hours later, a mile or two away, a different British battalion, the Suffolks, was charged with taking a German position codenamed Hillman. They spent seven hours between their first attack being launched and finally overrunning the battery. What fascinated me was that the Hillman position had been obviously known of for a long time and the whole Division’s advance was held up waiting for the Suffolks to storm Hillman because every time anybody tried to get past it the Germans hosed them with machine gun fire and anti-tank fire.

Why did the Suffolks take so long? Well, I looked at the casualties and they only lost seven dead, which for a battalion on D-Day was almost nothing. And then I looked more closely at the figures and almost all those seven were officers or NCOs. Now I’m an old cynic and what that told me, and was confirmed by what I learnt the more closely I looked at the story, was that the officers and NCOs of the Suffolks have been brave men who showed and led the way, but they had enormous difficulty in getting their men to follow. One of the aspects of war that doesn’t get much attention – and very few people ever write about it in unit war diaries or in accounts of what took place – was the fact that, again and again in wars, a brave officer or NCO will stand up and say, ‘Right chaps! Let’s go for it!’ and leap towards the enemy, then a minute or two later, he looks behind him and finds that he is all on his own or he only has a handful of men with him.

This aspect of things that how difficult it can be to get men to follow you in terrifying circumstances and especially when they’re new to it all. I find this fascinating and not nearly enough is said or written about it.

The sheer number of first-hand accounts that you have included in the book, it’s just extraordinary. What’s interesting is you write about how they report back that they’re pinned down. They can’t move.

That’s a terrible word: pinned down. It occurs again and again and again. Pinned down can mean almost anything. What it very often means if you’re dealing with troops who are new to battle is that they’re under fire and people are reluctant to get up again. I can remember from personal experience that when I was a BBC reporter in Vietnam, a very long time ago now, 50-something years, when I found myself in situations where we were being fired on and one was lying behind a tree.

It required a fantastic effort of will to get to your feet and to move in any direction. All one’s instincts were that one’s legs were jelly and that you stayed where you were. So I’ve known what it’s like to be in the situation that those men were in. Now another aspect of the story I’m telling, which is also very interesting, is the question of what is reasonable to expect from troops? And there’s no one simple answer to that.

One of the great historians of the campaign in Northwest Europe, Australian BBC correspondent Chester Wilmot, who wrote one of the great books published umpteen years ago, but still one of the classics, The Struggle for Europe. Now Wilmot landed with the 6th Airborne Division, only a mile or two from Hillman, and he was absolutely withering in his book about how sluggish the Suffolks and some other units were about moving towards Caen. He argued that it was their failure and their sluggishness and their refusal to take casualties to achieve objectives, as the Airborne did take the casualties and did achieve the objectives, that cost Montgomery’s great objective of taking Caen on D-Day itself.

But I’m raising a question in the book, was it reasonable to ask these guys to take the sort of casualties that you’re bound to take in a sort of last-ditch battle? Personally, I don’t agree with Wilmot and I don’t think we were ever going to get Caen on D-Day itself. There was just too little punch on the Sword Beach front and there were too many Germans between us and Caen.

I don’t think anything the Suffolks could have done would have changed the outcome on D-Day as a whole. I don’t believe the British could have got Caen. So was it reasonable to ask these guys to take the very heavy casualties to achieve a dramatic result?

It must make you think of the Falklands War in 1982?

I always remember in a different context after the Falklands. One day I was at a dinner at which Harold MacMillan was present and everybody was talking about the Battle of Goose Green in which the Parachute Regiment had 18 killed and I remember Harold MacMillan suddenly saying quietly, ‘In my war [the First World War] a battalion that had lost only 18 killed wouldn’t think that it had been in a battle.’ So everything is relative.

The plan is to get to Caen day one but if the plan relied on the Suffolks, a battalion like the Suffolks to push on through, regardless of casualties, then what does that say for the plan?

It’s a good thing to make ambitious plans. In fact, one of the criticisms of Montgomery as a general was often that he wasn’t ambitious enough. For example, before El Alamein in North Africa in 1942, Montgomery talked about hitting the Germans for six. Well, in the end, at Alamein, many historians and many soldiers at the time concluded that Montgomery hit the Germans for about three. But then, after that, I won’t quite say he let them get away, but he conducted the pursuit after El Alamein with an extraordinary lack of conviction and Rommel was able to withdraw in fairly good order after a suffering defeat.

So Churchill warned him again and again before D-Day. He said we’re not just seeking to create a bridgehead. This is the invasion of Europe. We need a serious result. Montgomery promised him, and Montgomery made wildly ambitious promises, I think very foolishly, that it was one thing to make a plan saying our objective is to take Caen the first day, but he was very rash to convey privately, especially to the American generals, his belief that he could realistically get tanks south of Caen on D-Day itself.

This was not a realistic objective. And yet the Americans always regard him as a bullshitter, always regard him as a man who promised more than he could deliver. This was emphatically true on D-Day. I don’t think it was ever a realistic objective to get Caen. The point of Caen was not the city. It was a vital road junction. It also opened the way once you were past Caen.You had a lot of open ground ideal for tanks in which you could hope to launch a big advance.

It would have been great to get Caen on D-Day, but the punch just wasn’t there. You can contrast Montgomery’s briefing before all the generals and warlords, before the King, before Churchill himself, before D-Day, when he talked about taking great risks to get armored brigades past Caen on D-Day. Yet in the end, by the evening of D-Day, what you had was as close to Caen as they were going to get that day: one company of the King’s Own Shropshire Light Infantry and half a squadron of Sherman tanks of the Staffordshires. They were very brave.

Sir Max Hastings is an award-winning historian and the author of thirty books including Sword: D-Day Trial by Battle. An extended version of this conversation is available here via the Aspects of History podcast feed.

Oliver Webb-Carter is the Editor and Co-Founder of Aspects of History.