What has been the reaction to Ovid as a character?

People think he makes a great main character – but I think many are surprised by how miserable he is in Poetic Justice. If anyone has read him, in Latin or translation, it tends to be extracts from his great work on mythology, The Metamorphoses. Also popular in exam specifications is his love poetry which gives the impression of someone who really enjoys life.

But in 8CE, the emperor exiled Ovid to the town of Tomis on the coast of the Black Sea and the poetry he writes there is quite different, depicting a suppliant desperate to find anyone who will help him get back to Rome. The Ovid who cheerfully gave the most politically incorrect advice on how to pick up women was nowhere to be seen and I found reading this poetry was occasionally embarrassing. I even caught myself muttering, “Get a grip!”

So what prompted you to write about him?

Well, it may not be the best feature of writers, but we do love a character in crisis, and Ovid’s exile was devastating for him. However, that does not make him likeable!

The second thing that made me want to write about him was the exile itself. The emperor Augustus used exile in a very personal way, famously punishing members of his own family for sexual transgressions. There is a real mystery surrounding Ovid’s exile though: the only contemporary evidence we have for it comes from Ovid himself, and he just tells us that he was exiled for his “carmen et error” (“My poem and my mistake”). Scholars have had a wonderful time ever since devising theories to explain what Ovid did – my favourite is that Ovid, like Actaeon seeing the goddess Diana in the bath, saw the wife of Augustus naked and had to pay the price. I’ve just written book three of my series which finally reveals my fictional solution to this mystery! No baths and no naked empresses.

Exile is different to physical punishments as well. For a reader, I would argue, exile is relatable in that we can all imagine how we would react to being driven out of our home on the whim of the man in power. I had a character with whom the reader would automatically wish to empathise, and yet the exile poetry told me that he could also be irritating. It was an irresistible challenge.

What made you decide to use Roman festivals in a murder mystery?

The great unfinished work Ovid left was The Fasti, a poem that was intended to lead the reader through year of Roman religious festivals. It’s serious, grown-up, erudite – I wonder what he was trying to prove? Ovid only got as far as June, even though he had years of exile to finish it, and we don’t know why he didn’t. But the festivals described gave me the idea of tying the action to festival days. Not only do I use it to tell the passing of time in the story, but when you live in a society used to the western Christian calendar, it is good to be reminded of just how different the Romans were. I also enjoyed including some of the unfamiliar festivals – like the day dedicated to Carna, the goddess of hinges.

What surprises your character Ovid in exile?

I don’t think Ovid expects to be made welcome or to make friends in Tomis. His ability to make people like him turns out to be his redeeming feature. For some reason, despite his grumpiness and his selfishness, Ovid makes friends. He is clever and funny and understands the human condition – when he thinks about any human condition other than his own. If you went to a dinner party and had your choice of Latin poets to sit next to, you’d choose Ovid.

What are the themes you wanted to explore?

Apart from how exile affects a person, I wanted to look at life in the Roman Empire for those who didn’t live in Rome. Sometimes our sources talk as though Rome is the only place to live, and I wanted to explore that assumption, because most people in the Empire lived their lives without ever seeing Rome. Rome sold people the story that she brought civilization and peace, but many societies managed civilisation for a long time before Rome came along. Tomis was about six hundred years old before Ovid set foot in it. Most of its citizens were Greek and would have considered themselves civilised, and I am sure that Ovid’s complaints about living in some barbaric wasteland would have irritated the people of Tomis immensely.

Who is Ovid’s greatest fan?

Apart from himself? I have two super-readers – my dad and a reader from Seattle who enjoys historical crime. They both love Ovid! I wish my tutor from Uni, Miriam Griffin, were still alive, I would love to send her a copy of Poetic Justice. My undergraduate essays used to make her laugh (which was not my intention, I can assure you) and I hope she would like my Ovid. She inspired my love of Rome and I’m very grateful to her.

You were a teacher before you started writing. Are you ever tempted to sneak some lessons into your books?

That is a wicked question! I don’t do it deliberately, but once a teacher, can you ever really escape it? I’m passionate about Rome, and I want readers to share that fascination for the ancient world. The one thing you definitely don’t do, if you want someone to love something, is lecture them about it. Oops — does even using the word didactic give me away?

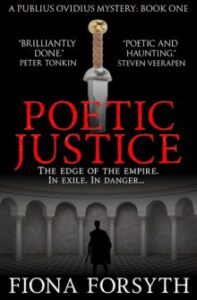

Fiona Forsyth is the author of Poetic Justice, a Publius Ovidius Mystery.