Neil Faulkner, your book opens in 1851 with the explorer and missionary, David Livingstone, who encounters what turns out to be a huge slave trade that stretches from Africa to India. Whilst Britain had abolished slavery in 1833, what were the numbers that were involved in this ongoing practice?

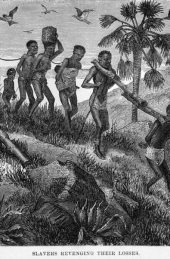

There are no precise figures, but a rough estimate is that the East African trade soared from around 10,000 a year in 1800 to five times that number by mid-century. This, though, is to understate the misery. Slave traders often killed all the men and took only women and children. They killed many more who fell by the wayside on the gruelling marches to the north. While untold more were displaced, deprived of their livelihoods, and simply died of starvation in the bush. So we might easily treble the total number of victims.

Why do you think we’re not more aware of this particular slave trade?

The focus is almost always on the West African trade because of the Eurocentric bias of traditional historiography, and perhaps also because there is a ‘good news’ story here, to do with the European, especially British, abolitionist movement.

You mention that it was this slavery, brought by Arab traders, that changed the methods of warfare in Africa, with humans providing the currency to purchase weaponry. Was slavery the driver for the Anglo-Arab Wars?

Yes, definitely. I think this is a very important theme in the book. On the one hand, you have surging demand for primary commodities because of capitalist globalisation. That drives the expansion of the East African trade. The most obvious case is ivory – carried to the coast by enslaved Africans – but in fact we then see those Africans being bought up to work producing other commodities, like sugar, cloves, gum, pearls, etc. The growing wealth of Ottoman, Persian, and Arab mercantile elites because of this boom in primary commodities also means increased demand for household slaves, concubines, and eunuchs. So the slave trade is the black heart of the Indian Ocean economy in the 19th century. Vast amounts of wealth are at stake. We are looking at a mercantile-slave nexus with tentacles all over the region. I haven’t the slightest doubt that the jihadist movements of the late 19th century were essentially slave traders’ revolts.

In the context of the ‘scramble for Africa, there are contrasting views of the continent and its people in Victorian Britain – David Livingstone represents one, and William Gladstone another, which was the more prevalent at the time?

Livingstone was much closer to public opinion, which was broadly abolitionist, especially in the liberal middle class and the organised working class. There had, for example, been strong support for the North during the American Civil War. The British ruling class was another matter. A lot of them had sympathised with the Confederacy, and few politicians (still elected, of course, on a very narrow franchise) showed much interest in abolitionism. The drive came from below. Gladstone, in particular, was a rank hypocrite, his liberalism only skin-deep.

How successful was Livingstone in publicising the ongoing slave trade?

Livingstone was centrally important – in books, lectures, and news reports – in building a new abolitionist movement around the East African trade, and then, of course, after his death, Henry Morton Stanley became his posthumous standard-bearer and probably an even more effective advocate of the abolitionist cause.

The death of Charles Gordon in Khartoum is often romanticised as Victorian stoicism in the face of a barbaric hoard, but just how inaccurate is this?

General Gordon’s Last Stand, by George W. Joy.

Very inaccurate, of course, because the Turco-Egyptian colonial administration in the Sudan – represented by Gordon – was barbarous, to say nothing of the barbarism with which British imperialism had smashed the Egyptian nationalist revolution led by Colonel Arabi Pasha in 1882. The view of the Victorian public was grotesquely distorted. That said, the Mahdist movement, and the subsequent Mahdist caliphate, were barbarous in their own way – an atavistic, reactionary revolt of slave traders and religious bigots that offered nothing progressive to the people of the region as a whole.

As you say in the book, Sudanese slavery was a societal norm at the time. How effective were individuals such as Gordon and Gessi in stopping it?

Gordon and Gessi were momentarily successful, and then, as soon as their hands were lifted, the thing surged up again. That was mainly because they were there to provide the Khedive of Egypt with political cover for what was really an attempt to expand Turco-Egyptian control and establish a state monopoly on the slave trade. There was no sustained politico-military drive behind the anti-slavery wars of the 1870s, and most of the Turco-Egyptian colonial administration was hopelessly corrupt and complicit.

Right around the publication we’ve seen the Taliban take Kabul, and at the end of your book, your quote of Aijaz Ahmad is striking – could one argue the departure from Afghanistan is the first step in seeking to resolve the challenges raised by Ahmad?

In the late 19th century, you had a symbiotic relationship between Western imperialism and Islamic jihadism: the one conjured the other. The result was an utterly dystopian conflict between European ‘coolie’ capitalism and the Arab slave trade. We’ve seen the same thing playing out in the last two decades with the so-called War on Terror. Western violence overthrows governments, bombards cities, imposes corporate power, and plunges whole societies into destitution and displacement. Out of the social wreckage arise jihadist movements, many of them plainly psychotic, where young men think they do God’s work by blowing up mosques and murdering schoolchildren. But who, finally, is responsible for this? Bush and Blair. But they learn nothing. So we have the international political elite still telling us that we what we need are more guns, more violence, more killing. Backed, of course, by the arms manufacturers, for whom the War on Terror is a god-send.

Neil Faulkner is a leading military historian, fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, features editor of Current Archaeology and a lecturer for the National Association of Decorative and Fine Art Studies. In his capacity as a research fellow of Bristol University, he has written academically on a variety of archaeological and historical topics, and is co-director of the Great Arab Revolt Project. He also edits Military History Magazine. Empire & Jihad: The Anglo-Arab Wars of 1870-1920 is his latest book.

Aspects of History Issue 6 is out now.

Neil Faulkner Neil Faulkner