David, congratulations on the new book. What’s the plot of the new series?

The new series follows the adventures of John Page, a real-life English soldier who served in Normandy during the reign of Henry V (1413-22). He misses the battle of Agincourt, but is outlawed and runs away in time to join Henry’s expedition to Normandy in 1417-1418. After witnessing all kinds of horrors, including the massacres at Caen and Rouen, Page deserts the English army and flees east, all the way to Bohemia. There he joins the followers of Jan Hus, a renegade priest who preached against the corruption of the Pope and the Catholic church. The followers of Jan Hus, the famous Hussites, fought a long war to preserve the independence of Bohemia, repelling a series of crusades thrown against them by the Pope.

Why did you want to write about the Hundred Years War?

The Hundred Years War is a very well-trodden subject, especially, but I thought there was scope to do something slightly different. In an earlier novel, the Half-Hanged Man, I had told the story of John Page’s father, a mercenary known as the Wolf of Burgundy. He came to a bad end, but I decided to turn it into a family saga and continue the tale through his illegitimate son, our hero.

I tend to write from a first-person POV, because I find it easier to write and makes the action more vivid and personal for the reader. This seemed an ideal way to present the wars in France, especially under Henry V; these were brutal in the extreme, and very different from the romanticised image of Shakespeare’s depiction of Henry as a ‘golden boy’ of English history. I wanted to show Henry as he truly was, warts and all, through the eyes of one of his soldiers. The king was an undeniably brilliant soldier and politician, able to leverage the political divisions in France to his advantage. Yet he had a very dark side, and could easily be presented as a villain. He was a religious fanatic, even by contemporary standards, perfectly willing to burn his subjects alive for their beliefs. One of them, Sir John Oldcastle, had once been Henry’s friend. Henry even had a suitably villainous scar disfiguring one side of his face, inflicted by an arrow at the battle of Shrewsbury.

Who is our hero John Page?

As I noted above, John Page was a historical figure. Unfortunately we know very little about him outside his only surviving poem, The Siege of Rouen. This is an eyewitness account of the English siege of Rouen, the capital city of Normandy, between 1417-1418. Famously – or notoriously – Henry refused to allow the starving citizens, expelled from the city as ‘useless mouths’ – to pass through his siege lines. This was a political choice, designed to make the French look incapable of defending their own, but it condemned hundreds of innocent people to a miserable death.

In his poem, Page expresses sympathy for these wretches, and pleads with the king to give them meat and drink. I thought that was interesting, as it implies Page had a bit of empathy, and wasn’t just another thug with a sword. Page was evidently an unusual character: not many English men-at-arms of this period, especially outside the nobility, were inclined to compose epic poems of their wartime experiences.

It would be good to know more about Page, but other than a few vague clues in the text, we know nothing of his background and origins. He may have served in the retinue of Gilbert de Umfraville, lord of Redesdale, but that is far from certain. The surviving muster rolls for French and Scottish campaigns of this period feature several archers and men-at-arms named John Page (not an uncommon name) and the poet might have been any one of them.

The huge gaps in Page’s career were an advantage for me, however, as it meant I could do what I liked with him! For instance, the real Page probably didn’t run off to join the Hussites – I suspect he died in Normandy – but his true fate is unlikely to be resolved. This is the beauty of writing about almost entirely obscure individuals.

The Burgundians are involved in the story, are they reliable allies?

Only so far as the alliance served their interests – the same could be for everyone else, of course, including Henry V. Most alliances of this period (or any other) were born of mutual interest i.e. strictly business, nothing personal. The Burgundian alliance held good for Henry’s short lifetime and in the early reign of his heir, Henry VI, but fell apart in the mid-1430s. It was no coincidence that the English war effort fell away at about the same time.

What came first, characters or plot?

I had a very rough outline of a plot – the war in Normandy and the Hussite wars – and how I wanted Page to fit into it. Otherwise I just started writing and let the narrative pull me along, so to speak. I’m usually a bit more structured and prefer to sketch out a plot in bullet points before setting anything down, but this was more of an instinctive process. It helped that I had already written a prequel of sorts, The Half-Hanged Man, and had always had the idea of writing further books in the series. That was a problem since I had helpfully killed off the main character (oops), until I hit upon the idea of using his son.

After Agincourt and the death of Henry V, was it inevitable the war would end in defeat?

The simple answer is I don’t know. It is wrong to say that everything fell apart immediately; Henry’s very capable brother, John of Bedford, kept the momentum going for about a decade and won a victory at Verneuil that was arguably even more impressive than Agincourt. Even he got bogged down eventually, however, especially after the rise of Joan of Arc. I suspect Henry’s prestige – he would have been crowned King of France at Rheims, remember – along with his personal drive and competence would have eventually resulted in a stalemate, rather than outright defeat for the English. That may have even resulted in a permanently divided France, with Henry and his heirs ruling over Normandy and Aquitaine in full sovereignty, while the rest was held by the Valois. That would have had all kinds of long-term consequences – but obviously I am just speculating.

Was Joan of Arc the difference between the two sides?

I think so, certainly as a figurehead. Joan was as astonishing figure, one of those national resistance leaders that seem to pop out of nowhere, just when their country needs them most. Another comparable figure would be William Wallace, although Joan achieved more. They both came to sticky ends, of course. On the other hand, the English did stage a comeback after John’s death, largely thanks to John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, known as the ‘Terror of the French’ and the English Achilles. Old Talbot won a string of battles against the French and recovered parts of Normandy, before charging straight into a cannon’s mouth at Castillon in 1453. He was the last hope for the English, however, especially with Henry VI and his nobles making such a mess of things.

What’s coming next?

I have just started work on a new series of novels about Philip of Cognac, the bastard son of Richard the Lionheart.

Much like John Page, Philip is another shadowy historical figure whom I can bend and shape as I please. His adventures on the Fourth Crusade will take him to Constantinople, the Queen of Cities, and beyond. The first novel is titled Outlaw Knight (I): Crusade, and will be available in ebook and paperback from 1 September.

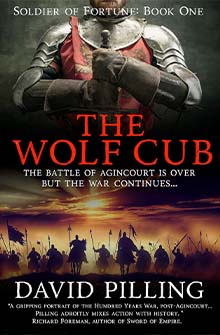

David Pilling is a historian and writer, and the author of The Wolf Cub, published by Sharpe Books.