Paul Beaver, your new book is on Reginald Mitchell, the aviation engineer who designed the Spitfire. What was special about Mitchell?

Mitchell was a very special engineer. At Supermarine, he fostered the right balance of experience and innovation, which for a small company was unusual. Mitchell did not, however, design the Spitfire per se, hence the biography’s subtitle ‘Father of the Spitfire’. Equal credit goes to his team, including the Design Team Leader, Alf Faddy, and his wing aerodynamicist Beverley Shenstone – and the other 150 people who worked on the Spitfire prototype, the Type 300.

What was the genesis for the Supermarine Spitfire?

The family tree of the Type 300 fighter project includes Supermarine’s Schneider Trophy-winning racing seaplanes and the technology they demonstrated: the power plant from Rolls-Royce and the use of cooling and stressed skin. The Air Ministry saw the benefits of harnessing this technology and, less than three weeks after the 1931 win, issued a specification for a fast, monoplane fighter. Supermarine’s first attempt, the Type 224, was a complete failure, but Mitchell was undeterred and brought in his trusted lieutenants such as Faddy and Shenstone, Joe Smith and Alan Clifton, to create a better design. The Type 300 was promoted by Vickers, the Supermarine parent company, and the Air Ministry wrote a specification around the project.

What was Mitchell’s chief requirement in the design of the Spitfire: speed, manoeuvrability or firepower?

Mitchell followed the Air Ministry specification for combat power, rate of climb, firepower and manoeuvrability through wing design. However, the Type 300 design did not pay enough attention to mass production – something alien to Supermarine, a cottage industry – and ease of maintenance, unlike the Hawker Hurricane and the German Messerschmitt Bf 109. Remember, too, that the Spitfire was not designed to dogfight but to destroy enemy bombers.

How conscious was Mitchell of the political situation – with the need for increased spending on airpower during the 1930s?

Mitchell, like every intelligent reader of newspapers, could see the gathering war clouds. But the notion that Mitchell wanted to design a fighter to combat the Luftwaffe is misplaced. Work started before the public announcement of the Luftwaffe and Mitchell, a director of Supermarine, wanted to build a fighter that the Air Ministry would order.

During this time Mitchell was suffering from bowel cancer. It seems incredible he was able to work. How did he deal with this illness, and did he receive support from his family and employer?

Mitchell was first diagnosed with rectal cancer in 1933 but was probably in pain for some time before. This would explain his mood swings during the design phase of the Type 224. He was operated upon in London and went into what today is called remission before the cancer returned. In early 1937 Mitchell, his wife Florence and his assistant Vera flew to Vienna for a last-ditch attempt at a cure. Mitchell was well supported by family and friends, including the Pickering family (George Pickering was one of the Supermarine test pilots).

The Spitfire is of course an iconic plane from the Second World War, but was it really the best of the war? Better than the P-51 Mustang, the Me-109, or even the Hawker Hurricane which downed more German aircraft during the Battle of Britain?

Each iconic fighter has its place. The Bf 109 (never Me 109) was the best German fighter until the later models of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, and was built in greater numbers than any other aeroplane. How amazing it would have been for Willy Messerschmitt and Reg Mitchell to have met! (The latter did correspond with Heinkel about wings!) The P-51D Mustang with all its British innovation, including the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, was the best long-range fighter, but that was not the role of the Spitfire. The Hurricane was half a generation behind the Spitfire but still deserves its place in the hall of fame. Much of the time, it was the pilot’s skill that made the difference – the number of Hurricane victories over the Bf 109E is impressive.

Speaking of the Spitfire’s British ‘rival’, how did Mitchell get on with the Hurricane’s designer, Sydney Camm?

I could find no evidence of Mitchell having met Camm. They were rivals for the Air Ministry contract!

I believe you yourself have flown a Spitfire. How does it respond compared with other aircraft?

I have been lucky enough to have owned a Tiger Moth and a Yak 52, poled the Bf 108B Taifun and undertaken conversion courses on the Harvard and Mustang, and spent 20 hours in Spitfires, learning the skills to fly it. The Mustang has a roomy cockpit designed by a pilot whilst the Spitfire is cramped and obviously designed by an engineer! The latter doesn’t even have a cockpit floor.

What’s next?

I have recently been in Germany researching the life of Willy Messerschmitt. It would make a neat juxtaposition with Mitchell.

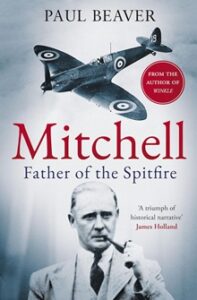

Mitchell: Father of the Spitfire by Paul Beaver (Elliott & Thompson) is out now in hardback from all good booksellers. Paul Beaver is an award-winning historian, bestselling author and vintage aeroplane pilot. He is deeply involved in the Spitfire including being a Trustee of the National Spitfire Project which aims to erect a fitting memorial at Southampton, the iconic aeroplane’s birthplace.