Why You Won’t Find King Arthur in My New Dark Ages Trilogy

As an undergraduate student, I studied the historical and literary sources for the legend of Arthur for my dissertation. It didn’t go well (slight understatement). I was then ‘punished’ for not doing well on that project, by only being able to find one part-time distance learning course when I came to my study for my master’s back in the early 2010s, and you guessed it, it was mostly about the legend of Arthur and indeed called ‘Arthurian Studies.’ But this hasn’t led me to hate Arthur (which might surprise you). It does, however, mean I’m sceptical about any possible historical Arthur, even though I will accept the Arthurian Legend has a history of its own, and it is a fascinating one. But for those seeking some answers to what was happening within Britain during the ‘true’ Dark Ages, roughly the period between about 410 and 600, Arthur and these legends are not where the answers will be found.

So, you might ask what my problem is with the possibility of a historical Arthur. After all, there are other names from long-ago times that I’m more willing to accept, such as Vortipor and his ilk. First and foremost, there is no mention of Arthur in any surviving written source until many centuries after it’s believed he lived. Some will cite the words of Gildas and his Latin text De Excidio Britanniae, dated sometime between about 480 and 540, as some sort of early and contemporary proof; however, Gildas doesn’t reference Arthur, even if he does mention a battle later assigned to Arthur by another early source, the Historia Brittonum. The perceived relevance, therefore, comes from cross-referencing two of the earlier sources, for Badon Hill is also mentioned in the battle list of the Historia Brittonum (surviving in a 12th-century manuscript), which does mention Arthur. And this is how trying to build a picture of the legends of Arthur continues; one source ‘might’ corroborate another, or it might not. Sometimes, in the frantic endeavours to find the ‘historical’ Arthur, people fall over themselves attempting to seek the much-desired ‘proof’ that these intriguing legends have a historical background. It would be fabulous if they did, but alas, this desire to ‘find’ Arthur so often overshadows what is already a thrilling, mesmerising, and complex situation. It also overlooks another captivating thread: the tracing of the development of the legend of Arthur with all its political significance. As is often the case, the legend of Arthur and its many iterations tell us more about the people and milieu of those who wrote the legends than about a ‘historical’ Arthur. In looking for the ‘proof,’ much else is dismissed as irrelevant and sometimes misunderstood as well.

However, the quest for Arthur has fuelled developments within archaeology, both in terms of technological advances and financial resources to discover so much more about the true ‘Dark Ages.’ No longer are archaeologists ‘looking’ for the characters who appear in the earliest surviving records, or rather for Arthur. Now, they search for the situations described. After all, it’s far easier to find evidence of war and large-scale population displacement than of a single individual. And just as easily, they can demonstrate that such displacements did not occur, contrary to what some early sources have claimed. Continuity, and not always change, is often found in the quest for the archaeological ‘truth’ of what was happening at this period, and if not always continuity or change, then the slow march towards something different from what had happened before. It is also revealing, excavation by excavation, that some of the written records we do have are potentially incorrect, or, if I’m being kinder, can’t be applied in such a widespread manner as has happened before to the whole of what is now England and Wales.

The historical and archaeological record of the true Dark Ages is filled with faceless and nameless individuals who were born, lived and then died. We often only have records of their burial or cremation. We often only have surviving metal objects, a meagre amount of clothing, and very few coins. These reveal more about the deaths of our ancestors than they do about how they lived.

It is time these ‘others’ received far more attention than a legendary figure who survives in much later source material. Admittedly, the Arthurian legend has been put to good use by a huge number of interested parties in the intervening period, from giving credence to claims to kingship (I’m looking at you Henry VII, and your son, named Arthur, who tragically died as a young man) to writers who genuinely believed a historical Arthur must have existed (Geoffrey of Monmouth and his little book) and therefore perpetuated the myth. While I could never reimagine this period in a non-fiction book, if it possible to do that when writing fiction.

This period fascinates me. It could be the lack of certainty about a great deal because I’m nothing if not a little lazy when writing my stories. But it is how these people lived that I want to bring to life. The Dark Age Chronicles are a story not of a ‘historical person’ as my books so often are, but rather of fictional people who ‘might’ have lived in this reimagined period. What was it like to live in a world inhabited by the physical remains of Roman Britain? Did people revert to the Iron Age tribal affiliations, or did the centuries of Roman rule make them live in an entirely new way? Who spoke what language? Who revered which God or Gods? Did they travel large distances? Did they not? Did they fight their neighbours or live in peace? How did they contend with drought, famine and plagues? Too often, this period is overlooked, the allure of the downfall of Roman Britain and the emerging earliest Saxon kingdoms absorbing our attention, but the interval between these two is upwards of two centuries. We all know a great deal can happen in a matter of weeks, let alone in the space of two hundred years.

And so, you won’t find Arthur in my new Dark Ages series, but you will find a lived experience where family, betrayal, and the need to survive dominate. If you would like to explore this period for yourself, then I recommend two excellent non-fiction accounts. If you prefer an archaeological exploration, Britain After Rome by Robin Fleming, and if you’d prefer one with more of a nod to the source material, but which will entangle you in the archaeology as well, The First Kingdom by Max Adams.

Mind, if someone does find a grave that genuinely has a ‘Here be Arthur’ marker on it, I’ll happily eat my words, and maybe, let him have a little starring role.

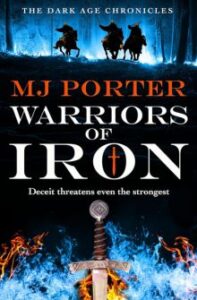

M.J. Porter’s historical fiction covers the periods of the Early English, Vikings and the British Isles as a whole before the Norman Conquest. She is the author of Warriors of Iron, the first of the The Dark Ages Chronicles.