The West African slave trade has become a staple of history teaching and popularisation. Rightly so. The triangular trade – trinkets from Europe to Africa, slaves from Africa to the Americas, plantation commodities from the Americas to Europe – was the most visceral expression of the brutality of early capitalism, a system ‘dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt’ (Marx).

A Zanj slave gang in Zanzibar

But even as the West African slave trade being shut down in the early 19th century, the more ancient East African slave trade soared to new peaks. From medieval times, Arab merchants had traded in the ‘black ivory’ of sub-Saharan Africa – overland across the desert, in riverboats down the Nile, in sea-going dhows sailing northwards and eastwards across the Indian Ocean, heading for markets in Egypt, Arabia, Persia, and Turkey. But this trafficking of Africans rose from around 10,000 a year in 1800 to around five times that number by mid-century. And for every slave who made it to market, many times that number were killed in slave raids or died in transit. And the shock-waves of violence and displacement involved tore apart the lives of those who remained.

The slave trade was booming because the world economy was expanding exponentially. The demand for primary commodities was insatiable. The Arab-Swahili merchants of Zanzibar – the principal emporium on the East African coast – were growing rich dealing in cloves, cowries, gum-copal, animal hides, sesame seeds, coconut products, beeswax, tortoiseshell, and, above all, in ivory and slaves.

The products of Africa, incorporated into a hundred and one different consumer goods, ended up in every Victorian drawing-room. Especially ivory, which was transformed into such accoutrements of Victorian gentility as combs, handles, fans, dress accessories, ornaments, sculptures, billiard balls, and piano keyboards. The ‘ivory frenzy’ would eventually see the hunters killing around 100,000 elephants a year.

The killing was the easy bit. The problem was transporting the goods. Ivory was heavy, the trails were long, animal traction was precluded by endemic disease, and free labour was not available in quantity. So slaves were used as porters. And this doubled the profit, for they too could be sold at the coast, some destined to work on clove plantations on Zanzibar, sugar plantations in the Indian Ocean, cotton plantations in the Nile Delta, date plantations in the Persian Gulf, or pearl fisheries on the Muscat coast, others to work as guards, domestics, concubines, and eunuchs in the households of Arab sheikhs, Turkish pashas, and Persian landlords growing rich on the profits of trade.

The ivory-slavery nexus. Trade was booming because Britain had turned itself into the workshop of the world and a maritime empire. A frenetic process of capital accumulation was transforming the global economy. The slave trade was booming because of globalisation.

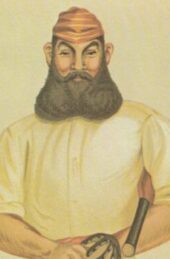

Charles George Gordon in Egyptian uniform

Here was the tap root of the historical tragedy that unfolded in North-East Africa between 1870 and 1920. It began as a humanitarian mission spearheaded by men of conscience like David Livingstone, the missionary, explorer, and abolitionist campaigner, and Charles George Gordon, the maverick general who, as governor-general of the Sudan, waged the first anti-slavery war in the late 1870s. It evolved into a war of conquest and subjugation by British imperialism – a war to crush an Egyptian nationalist revolution in 1882 and impose debt-peonage on the Egyptian peasantry in the interests of Anglo-French bankers. It triggered an Islamic holy war, a reactionary revolt of Arab slave traders, led by a charismatic Muslim preacher who proclaimed himself ‘the Mahdi’. It culminated in an apocalyptic confrontation between the industrialised machine-warfare of the world’s leading superpower and the fanatic bravery of tens of thousands of Arab tribesmen in one of the poorest regions on earth.

It was tragedy in that neither protagonist offered anything progressive to the great mass of the people of North-East Africa – the Nile farmers who lived by their own labour, the sub-Saharan tribesmen preyed upon by the slave traders, the women whose lives were vitiated by patriarchal oppression. It was a contest of revival dystopias, one rooted in the ancient slave trade, the other in modern ‘coolie’ capitalism.

And the lessons echo down the decades to the War on Terror – where, once again, Western imperial violence has conjured a genie of Islamic jihadism, creating a swathe of mayhem that stretches from Central Asia across the Middle East to West Africa.

Neil Faulkner is the author of Lawrence of Arabia’s War and Apocalypse: The Great Jewish Revolt Against Rome AD 66-73. Empire & Jihad: The Anglo-Arab Wars of 1870-1920 is his latest book and is published by Yale University Press.