Exit Ghost, by Philip Gooden.

It’s not the best part I’ve ever played or the biggest but it’s the one that had the greatest effect on my audience. In fact I’ve never seen an audience reaction like it. Very pleasing, in one way. Very unpleasing in another.

Every time I have these mixed feelings, I remember the money. Sixty-five shillings for what was barely an hour’s work. As a new member of the Chamberlain’s Men in the Globe playhouse in Southwark I earn a shilling a day. For this particular piece of work outside the Globe I got the equivalent of almost three months’ pay, all of it earned in a single hour on a September evening.

Was it worth it, what I had to do for that pile of gold coins? Sometimes I think yes, sometimes I think no. You’ll have to judge.

It started with Julius Caesar’s sickness. Not the actual Caesar, the one who’s hacked to death by his friends’ daggers in the Roman senate, but the actor who was playing the part in the play of the same name by William Shakespeare. That actor was…well, I’m not going to give his name. Let’s just call him Robert. There are and were quite a few Roberts in the Chamberlain’s Men. All I’ll say that this particular Robert was getting on a bit in years, at least 40, and that sometimes other things took precedence over mere acting. Things like draining a tankard or three in one of Southwark’s many taverns, or spending time, money and seed in one of Southwark’s many brothels.

Presumably he was doing one of those two things on that sunny September afternoon when he should have been appearing on the raised stage of the Globe in front of an audience of several hundred. The groundlings were standing below us and the higher-ups were sitting around us on their benches and in their boxes. We were coming to the end of the action. The moment when it’s all gone wrong for the conspirators. Julius Caesar is dead, Mark Antony has whipped up the mob in the forum, orating his heart out over his friend’s corpse, and Brutus and Cassius and the rest of the conspirators have fled Rome.

They end up in a place called Philippi, which is in Greece (I think), pursued by Mark Antony and Octavius, Caesar’s nephew. There’s a battle on its way. Brutus and Cassius aren’t going to survive it. The audience, groundlings and higher-ups, were looking forward to the battle, looking forward to Brutus and Cassius falling on their swords, full of fine words.

On the night before the battle Julius Caesar appears for one final time, to Brutus as he sits pondering in his tent. If there’s one thing an audience likes more than a battle and a falling-on-your-sword speech, it’s a ghost. Sometimes I think they’d pay to see the ghost alone.

I realised something wasn’t right after I’d come off stage, or rather been beaten off it. I was playing Cinna, not Cinna the conspirator and assassin, but an unfortunate Roman who goes by the same name and is consequently manhandled to death by the mob. I was dusting myself down and wondering whether they’d had to manhandle me quite so eagerly when I heard Dick Burbage say to the tire-man, in a loud whisper: “Jesus! Where is he then?”

“Don’t ask me,” said the tire-man, a fellow called Bartholomew Ridd. “I’m not responsible for the players.”

Ridd looked after our costumes. For him, only the costumes mattered; players were no more than a nuisance who damaged his clothes. Ridd caught sight of me staring.

“Ask Nicholas Revill there. Perhaps he knows where your precious Caesar is.”

Dick Burbage, who was our chief actor and part-owner of the Globe, looked in my direction. I shrugged in what I hoped was a helpful kind of way.

“I know where the bastard’s gone,” said Burbage, gesturing

over his shoulder to the outside world. In other words, in the direction of Southwark, with its taverns and brothels. “And he won’t be back soon either.”

He came closer and peered at me.

“You’ll do, Nicholas,” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “I will.”

I was still a bit in awe of Burbage at that stage.

“Do what?” I said.

“Take over Master Robert’s part of course. Play the ghost of Julius Caesar before the battle of Philippi.”

“I – I don’t know the lines, Master Burbage.”

“For God’s sake, Nicholas, are you a player or aren’t you? The ghost of Julius has, let me see, three lines, three lines only. Do you think you can learn those in the next twenty minutes. And get into your costume. And apply some white to your face to make yourself ghostly.”

These were more commands than questions. Dick Burbage said one last thing – “Remember to use the trapdoor” – before he spun on his heel and prepared to go on again. He was playing the part of Brutus.

So twenty minutes later I found myself clad in a sort of white nightgown and, my face smeared with white paste, clambering up the ladder that led to the trapdoor set in the floor of the stage. Ghosts generally enter like this since they’re supposed to be emerging from limbo or the underworld. The audience always likes to see people coming through the trapdoor. There was a gratifying collective gasp as I wavered into view.

Dick Burbage was there as Brutus, sitting alone in his imaginary tent, pondering on the battle the next day, fearing the worst. Master Burbage looked utterly different from the bad-tempered, exasperated actor-owner of a few minutes earlier.

I delivered my lines – sixteen words altogether – in a sonorous voice but also with a touch of hoarseness as if I wasn’t used to talking. I don’t suppose there’s much talk in limbo. I was pleased to see that Burbage looked alarmed at me, though he was only acting of course.

It all went off finely. I was so pleased with myself that I nearly added an extra threat or two to my three lines, but thought that would be unprofessional.

Afterwards Burbage patted me on the shoulder and even William Shakespeare, who was himself something of a ghostly presence at the Globe (you could never be sure whether he was there or not), nodded benignly at me. In the meantime I’d realised out what must have happened with Robert, the absconding player. Julius Caesar gets assassinated in the middle of the action and then makes only one more appearance so as to utter those sixteen words in Brutus’s tent. About an hour passes between his assassination and his emergence as a ghost. An hour is enough time to exit the playhouse, enjoy a rapid ale or fumble in tavern or brothel, and then return for your final few moments on stage. Not very professional, but it could be done. As long as you remembered to be back in time…

When Robert did eventually return as the audience was beginning to dribble out of the Globe at the end of the performance and the afternoon, he was berated by Burbage and fined three shillings on the spot. Burbage also made a point of saying in my hearing, “But look here, Master Robert, Nicholas did a very good job standing in for you as the ghost of Caesar. A very good job indeed. We hardly noticed you weren’t here.”

And that might have been the end of it. But it seemed that Burbage and Shakespeare weren’t the only ones to have appreciated my turn as Caesar’s ghost.

Having got rid of my costume and cleaned the white paste off my face I emerged from the playhouse with a couple of my fellow players. They were young men like me. No wives, no burdens, no responsibilities. We had the early evening in front of us. It was mild September. The very things that had tempted Robert – tavern, brothel – might have tempted us.

They may have tempted the others. I don’t know because we’d walked only a few yards down Brend’s Rents, the street outside the theatre, when I noticed a man beckoning to me from a doorway on the other side. Normally I’d have ignored him. We players occasionally get solicited for, well, for various favours, outside strictly theatrical affairs.

This individual didn’t look like one of those solicitors, however. He was small, respectably dressed, and his look and beckoning gesture were friendly rather than imploring. I veered off towards the doorway, telling the others I’d catch them up.

“Master Revill?” said the man. “Master Nicholas Revill?”

“Yes.”

I was surprised, but not that surprised, he knew my name. It is easy enough to discover a player’s identity. His voice, too, was reassuring. Pleasant, educated, civilised.

“I admired your performance, sir.”

Now I was surprised. Did he mean my performance as Cinna, beaten to death by the mob? Or a couple of other small parts I’d taken earlier in the play? But it wasn’t those.

“You were a perfect ghost, Nicholas. If I may call you Nicholas?”

He was almost deferential.

“You may, sir,” I said. No player is immune to flattery and friendship. “But your name..?”

“Forgive me. I am Nicholas too. Nicholas Adamson.”

It is odd but true that if you meet someone who shares your name you feel better disposed towards them. Off your guard even. Still, I did wonder where this brief encounter was going. I turned my head and noticed my friends rounding the corner of Brend’s Rents.

Now Nicholas Adamson spoke more urgently.

“I wasn’t the only one to admire your performance as the ghost of Caesar. I have an employer who was with me at the playhouse and who was struck even more keenly.”

“Oh yes?”

“My mistress is a very comely lady.”

‘Oh yes,” I said, growing a little suspicious now.

“She would like to meet you. She has a proposition.”

“If you’ll excuse me, Master Adamson, I will be going now. My friends are waiting.”

“As an earnest, she asks you to accept this,” said Nicholas Adamson, ignoring what I said and handing me a crown. Five shillings.

I held the little gold coin between thumb and forefinger. It was almost a week’s wages.

“There’s more, a good deal more.”

“What do I have to do?”

“I can’t explain now. Later though. Do you know the Ram tavern? It’s in Moor Street in Clerkenwell.”

“I know it.”

“Be there at eight o’clock this evening. You will meet her. She is comely. And this is just an initial payment.”

With that, he spun on his heel rather as Dick Burbage had done earlier backstage, leaving me suspicious and confused but still holding the gold crown.

***

I could have done nothing. I could have pocketed the money and gone searching for my friends in whatever tavern or brothel they’d found this side of the river. But seven o’clock saw me striding across London Bridge and then a little west of north towards Clerkenwell.

It was an adventure. I was interested to see the comely lady (what was her proposition?), interested in the prospect of more money (how much?). They couldn’t be planning to rob me. What robber begins his crime by handing out money? Besides no one in their right mind would think to rob an apprentice player.

As for trickery, I was confident I could see through anything. Altogether I was in a cocky mood. Hadn’t I just triumphed as Caesar’s ghost and been praised for it? Whatever happened, I could take care of myself. An adventure, as I say.

I’d visited the Ram a couple of times on previous business. It was a rather dingy tavern on the borders of the city, just outside its walls. It seemed an odd place for a rendezvous though it was, I suppose, out of the way. The Ram was owned, or at least run, by a woman called Bridget Goodride. By all accounts Mistress Goodride once lived up – or down – to her name but she has since grown old.

By the time I reached the tavern darkness had fallen. Inside the air was smudgy and smoky from the candles. I was hardly beyond the door before a voice hissed my name from a nearby alcove.

Nicholas Adamson was sitting at a table, illuminated by a single candle. looking a little out of place in his smart, respectable clothes. In the back of the alcove, in the inmost shadow, was a lady. I could tell that from the glimmer of the candle on the silk she wore and the white of her ruff. The ruff cast a little light up into her face but revealed no more than full lips and unblemished skin. A hat shadowed her eyes. She looked even more out of place in the Ram than he did.

Adamson indicated I should sit next to him and opposite her. He summoned the pot-boy, who limped over. I remembered him from previous visits. His name was Gilbert. Adamson ordered another tankard of ale for himself and one for me, without asking what I wanted. The lady was drinking something different since the light twinkled off a delicate glass. While we waited for our drinks I wondered whether Mistress Goodride kept the better drinking vessels for the better class of customer. And I wondered about the identity of the lady opposite me, in the shadows.

As if reading my thoughts, Nicholas Adamson said, “This is Mistress Margaret Norris. My lady, this is Nicholas Revill.”

I inclined my head slightly, said something about the pleasure of meeting her.

“Nicholas,” she said, and I thought for an instant she was addressing me but it was Adamson. “Would you put the candle nearer to Master Revill, so I can see him more clear.”

Her voice was soft, almost insinuating. Adamson pushed the candle so close that I could feel its heat under my chin. The smoke tickled my nostrils. Margaret Norris made a gentle sound somewhere between a gasp and a sigh.

Gilbert came limping across with the drinks. She waited until the potboy had gone and then said, “Yes, he is like, very like. I thought so in the playhouse this afternoon and now I am sure.”

“Like who, madam?” I said.

“Like Mistress Norris’s son, Thomas,” said Nicholas Adamson.

“Like my husband’s son,” she corrected. “Thomas was my husband’s first wife’s son, and so my stepson.”

“Was,” I said.

“Yes, alas, he is no more,” she said. “But, seeing you, Master Revill, it is as if he has come back to life again.”

The hair on the back of my neck stirred slightly. To be told you look like someone who is dead may not be comforting.

“To the quick of the matter,” I said, speaking directly to Mrs Norris. “Your – your friend here gave me a crown today – ”

“Nicholas Adamson is my steward,” she said. Adamson’s head bobbed as if in acknowledgment of his title.

“Your steward then, Mistress Norris. He said you had a proposition for me. I’d be glad to hear it and then, I think, to repair to my lodgings. It’s late and I’m tired. I have been working all day.”

It wasn’t so late and I wasn’t so tired but I thought I’d make the point.

“I think you’ll find your time is not wasted, however late,” she said. “Listen to what I have to say and then consider my request.”

So I listened.

It was a peculiar story and an even more peculiar request.

Mrs Norris said her husband was older than her, by more than a few years. Her husband’s name was Edward. When they married, he already had a son, Thomas, who accordingly became her stepson. Thomas was a grown man by then, about your age, Master Revill, she said, and with something of your looks too.

Dick Burbage

Now this Thomas was a little wild though good at heart. Mrs Norris said that she got on well with him. But he drank too much and mixed with the wrong people. Perhaps because of this or for some other reason he had come to to a sad end this very summer. His corpse was discovered one bright June morning not far from the Fleet Ditch. He had been stabbed. His pockets had been emptied, and some items of jewellery – rings, brooches – stolen. No perpetrator had been apprehended.

On hearing the news of Thomas’s violent death, her husband Edward had suffered a seizure. He had taken to his bed where he remained three months later. He was alert but not altogether in his right mind and quite without spirit. When he talked it was only of Thomas, poor Thomas. Sometimes he appeared to think that his son was still alive. Sometimes he looked expectantly towards the door of his bedchamber as though Thomas was about to walk into the room.

When she reached this point in her story, I realised what Mrs Norris was aiming at so I interrupted her.

“I hope you do not think I am going to impersonate Thomas and pretend he is still living.”

“No,” said Mrs Norris, “I want you to impersonate a dead Thomas. A ghost come back from the grave to assure his father that all is well, that he is at peace and sleeps soundly.”

“It’s an absurd idea, madam,” I said, making to get up from the table.

Nicholas Adamson put a restraining hand on my arm.

“Wait, Nicholas, please,” he said. “Hear my lady out.”

I sat down again. Against my better judgement, I listened. Mrs Norris believed – or pretended to believe – that if I, who looked so like her late stepson, were merely to appear in the door of her sick husband’s room and utter a few words of reassurance, then that might, just might, be enough to give Edward a little peace and rest of his own.

“Please, Master Revill, at least consider my idea. I cannot bear to see my husband suffer so. You are his only hope.”

There was a good deal more of this persuading and pleading. At some point she nodded at her steward and he produced a little drawstring bag from his pocket, untied it and allowed me to peek into the interior. A clutch of gold crowns glinted in the candlight.

“There is sixty shilling here in crowns,” he said. “It is all yours if you do as my lady suggests.”

I looked towards Mrs Norris. I couldn’t see her eyes under the shade of the hat but those full lips mouthed a ‘please’.

“Sixty shillings to play a ghost?”

“Sixty-five,” Adamson reminded me. “You already have a crown.”

“As you played a ghost so superbly this afternoon, Nicholas,” said Mrs Norris, stressing my first name and larding me with flattery.

“Very well,” I said. “When do I go on stage as the ghost of Thomas?”

“Why not now?” she said.

***

I’ll be brief in describing what happened next. It’s painful to have to go through it again. Mrs Norris’s house was not far from the Ram tavern. I suppose that was why she had selected that as our meeting place. Her house was a big place, standing by itself, with its own wall and garden. The moon was rising and almost at the full, and the trees in the garden cast moon-shadows on the ground.

Once inside the house, Mrs Norris took my arm and indicated we should enter a small chamber by the front door. It was dimly lit but still better illuminated than the alcove in the Ram. There was table on which were arranged some jars and pots, and a couple of chairs. I understood then that everything had been prepared beforehand.

She gestured towards one of the chairs.

“Sit down, Nicholas. We must make you ready.”

I sat down. I had a better view of Mrs Norris now since she had removed her hat. She was indeed, in her steward’s word, ‘comely’, with fine golden hair. She scooped something out of one of the pots and came close and applied the mixture to my cheeks.

“What are you doing?” I said but not very sharply since I was enjoying the fact that, to get close to my face, she chose to press her breasts against me.

“Applying some white, Nicholas. You are meant to be a ghost after all. Don’t worry. It is only a mixture of vinegar and lead. I use it myself. Don’t you use it in the playhouse?”

True, I had applied white paste this afternoon as Julius Caesar’s ghost, though I didn’t know what it was made of. Mrs Norris wiped her fingers on a piece of rag and dipped them in another pot. This time she scored a red slash down my right cheek.

“What’s that for?” I said.

“Remember that Thomas was stabbed. One of the wounds was to his face. My poor husband knows this. He saw his son’s body afterwards. He will believe in you more easily if you appear to him exactly as he last saw you.”

Something about this explanation didn’t quite ring true but, as if to smother my doubts, Mrs Norris pressed herself still more insistently against me.

“You are very like him, you know,” she said, standing back to admire the finished effect. So struck was she by my likeness to the dead Thomas, that she lent forward again and kissed me full on the lips. Her breath was sweet with whatever she had been drinking in the Ram.

“And my clothes?” I said, when she had finally drawn back and I had recovered. “What costume should I wear since I am playing a part?”

“Go as you are,” she said. “Like most men, my husband doesn’t notice what people are wearing.”

She told me to wait in the lobby outside while she went up to her husband’s chamber to ‘prepare the way’ as she put it. Her steward would signal when it was the moment for me to go up the staircase and enter.

“Remind me what I have to do again,” I said, feeling uneasy all over again despite those sixty-five shillings.

“Take this candle from here and hold it beneath your face so he can see you clearly. Simply stand in the doorway for a moment. Advance a few feet into the room. Smile as if you are pleased to see your father once more. Smile and smile. Utter some words of reassurance. ‘All is well.’ ‘I rest in peace.’ Whatever you like.”

With that she went upstairs. I waited for several minutes in the lobby. It was very quiet. The rest of the household must have gone to bed. I wondered whether I looked as foolish as I felt with my whitened face and a red slash down one cheek. Strange that I never felt foolish before going on stage at the Globe however outlandish my appearance or costume.

There was a whispered ‘Nicholas’ from the top of the stairs. It was Adamson. He beckoned me up. At the top of the stairs he indicated a facing door. He adjusted the candle so that it lit my face from below. I felt its heat. When I was in position he reached over and gently lifted the latch. As the door swung open he almost pushed me into the room with a hand on my back. He himself kept out of view.

There were two people in the room. One was Mrs Norris, sitting on the edge of the bed, a four-poster. In the bed was a man, presumably Edward Norris. He was old, older than she’d led me to believe. He was sitting up, supported by bolsters. He had staring blue eyes and bristling white eyebrows. The bedchamber was surprisingly well-lit, considering it was a sick man’s. Afterwards I realised why there were so many candles burning.

It was so that Mr Norris might see me better.

He saw me all right.

Mrs Norris did her best to ensure that. As I stood in the doorway, as instructed, she grasped her husband by his wizened upper arm, pointed at me with her other hand, and screamed.

It was a muted scream, as if she didn’t want to waken a sleeping household.

His mouth formed an O. His blue eyes widened. He extended his free arm and pointed a quavering arm towards me.

“Lord save us!” said Mrs Norris “Angels and ministers of grace defend us!” I moved forward. I smiled and smiled, as I’d been told.

My heart was thudding but I heard myself muttering some words of reassurance, of consolation. ‘All is well, father.’ ‘I rest in peace. Do you likewise‘ That sort of thing.

It’s doubtful whether the old man could have heard me since Mrs Norris was keeping up her quiet screaming, like a whimpering dog. In the intervals of whimpering she garbled prayers for protection. I don’t think Mr Norris was aware of any of her words either, or of his returning son. I don’t think he was aware of anything.

His quavering arm sank slowly, then his limp frame shook, once, twice, three times, and went rigid.

After what seemed like hours but was probably only a few minutes I felt myself being almost forcibly tugged from the room and hurried down the stairs by Nicholas Adamson. In the lobby once more, he pushed the little draw-string bag into my hand, opened the front door, almost ran with me down the front path, unlocked the front gate, pushed me through into the street, and secured the gate with him on the garden side.

I stood there, quite bemused. When I’d gathered my wits I contemplated banging on the door and demanding re-admittance. But I didn’t. Instead I turned tail and ran through the moonlight. I wanted to get back into the city before the watchmen closed the gates for the night. I felt weighted down by the sixty, actually sixty-five, gold crowns I was carrying. For some reason, although I doubted everything I’d been told by Nicholas Adamson and by Margaret Norris, I didn’t doubt they’d been as good as their word and paid me the agreed price for whatever nefarious business I had been engaged on.

***

It was thirteen pieces, I noticed, as I tipped out the contents of the little draw-string purse in the safety of my lodgings that night. Sixty-five shillings equalled thirteen crowns. Thirteen pieces, albeit of gold not silver, seemed an ominous number. Who had I betrayed? And why?

A long time passed before I found out what had really been going on that Clerkenwell house. By the time I did find out, the money I’d received had more or less gone (those Southwark taverns and brothels). On two occasions I went back and stood outside the blank walls of the Clerkenwell house though I don’t know what I expected to find.

One evening in the spring of the following year I emerged from the playhouse to find a gentleman waiting for me. It was Nicholas Adamson, the steward. He somehow looked more respectable than last time.

He wanted to explain, he said. His lady had sent him.

We secluded ourselves in a corner in one of the Southwark taverns, a place known as The Knight of the Carpet.

Adamson informed me that the story I’d been told was almost true. There was young man called Thomas, he did look very much like me, etc. But he was not Mrs Norris’s stepson but her ‘friend’.

“Lover, you mean,” I said.

“Friend,” insisted Adamson.

Old Edward Norris, suspecting his wife and hating his supposed rival, arranged for the young man’s death through several intermediaries. Nothing could be traced back to him. Yet once the deed was done, he fell into a kind of guilty sickness.

Knowing her husband and what he was capable of, Mrs Norris determined on revenge for his crime. Having already seen me on two previous visits to the Globe, and been struck by my likeness to her ‘friend’, she primed Adamson to approach me after I had, by chance, played the part of Julius’s ghost. That coincidence gave a very fortunate opening to the task, the proposition she had for me, that I should play the ghost of her murdered Thomas. She meant for Edward to be severely terrified by the apparition of his late rival, even perhaps terrified to death. After all, he was old and sick.

My appearance at the door, candle held under my features so they appeared ghastly, together with my white face, my skull-like smile and the dagger slash across my cheek, was enough to push him over the edge.

I remembered the way Mrs Norris had kissed me after dabbing on face-paint. Of course, it was her lover she was kissing not her stepson. Not Nicholas Revill either.

“No blame attaches to you, Nicholas,” said Nicholas Adamson. “He was a nasty man, a murderer at one remove. He deserved to die.”

“What has happened to Mrs Norris?”

“She – she is intending to remarry,” he said, “as soon as the necessary period of mourning is over.”

“But her lover, her friend Thomas, is dead,” I said.

“There are others who have long admired her,” he said, picking delicately at a speck of dust on his new smart apparel. “Now she has looked favourably on one of them. A lady may marry her steward, after all.”

What better way to silence an accomplice than to marry him, I thought.

Or to pay another accomplice off with thirteen pieces of gold.

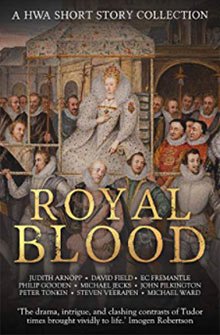

Philip Gooden is the author of The Salisbury Manuscript, published by Sharpe Books. This story is from Royal Blood: A HWA Short Story Collection, also published by Sharpe.