What kind of historical heretic would even ask that question? Of course, Hadrian’s Wall is a masterpiece, an extension of Imperial power that has seized the imagination over almost two millennia, and is still recognised today as one of the wonders of the world. A masterpiece not just of the builder’s art and the skills and discipline of Rome’s legions, but a confirmation of its creator’s vision. It separated the people of Britannia from the barbarians of the north for almost three hundred years. Any native tribesman who watched it being built would have looked upon it with the same awe that you or I would gaze upon a giant alien spacecraft hovering over Buckingham Palace. But what was the creator’s vision?

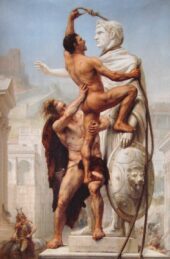

Bronze of Hadrian found in the Thames.

When I was researching and writing The Wall, I had to study Hadrian’s great northern barrier from every possible angle, and as my knowledge grew, so did the questions. Hadrian was of a tidy disposition and he had form for creating dividing lines between the Empire and what were considered barbarians. The Historia Augusta records, in what was probably a reference to the Limes Germanicus, to the east of the Rhine: ‘Hadrian shut them … the barbarians … off by means of high stakes planted deep in the ground and fastened together in the manner of a palisade.’ But why divide a relatively small island when Agricola had proven a few years earlier that Rome was perfectly capable of conquering it all?

Normal Roman policy was to forge alliances and create buffer states between the Empire and its enemies, backed by a strong, flexible and mobile military presence. Hadrian’s decision to build the wall and its forts went against every tactical doctrine of the Roman army. A legion didn’t fight from behind walls, except in extremity. Its strength was in its manoeuvrability, its discipline and its ability to get its swords into the very vitals of the enemy. Now, between five and ten thousand specialist light infantry would be forced onto the defensive, walking parapets and limited to localised patrols.

And this wasn’t a decision driven by fear of some great threat from the north. There’s little evidence that a powerful tribal federation existed in what is now Scotland before Agricola’s invasion. The Vindolanda Tablets, those fascinating slivers of wood that give us such an insight into Roman life on the frontier and the mindset of a fortress garrison, provide remarkably few references to conflict. In fact, as Anthony Birley states in his excellent ‘Garrison Life at Vindolanda’ not a single tablet refers directly to any fighting.

The likelihood is that Hadrian built his wall because he could – it was a symbol of his power and prestige – because there was little beyond the Solway-Tyne isthmus to attract an avaricious Roman Emperor, and because he had plans for Britannia’s legions elsewhere at some point. The defence of the province could now be left to the easily replaceable Batavians, Tungrians, Gauls and Asturians of the auxiliary cohorts.

Naturally, they would also be required to turn a profit. The wall, as originally devised, was designed with no less than eighty gateways along its length. These would have been used to control trade between north and south, and, as was Rome’s way, to milk tolls and taxes from every last egg, bushel of corn and hunting dog that passed through in either direction.

That function changed as the decades passed, and the number of gates fell to fourteen as more and more were blocked up, an indication of changing politics and attitudes. A hardening of the frontier divide. The wall became a self-fulfilling prophecy that trapped not just the soldiers who garrisoned it, but also Imperial minds. In almost three hundred years it was abandoned in its entirety only once, when Antoninus Pius needed his own modest triumph and extended the empire a hundred miles north for a few decades.

By the time Marcus Flavius Victor traverses its length on the way to ignominy or glory as the fates decide, the wall forts are crumbling, along with the morale of their unpaid, underappreciated and undermanned garrisons. The wall’s time is nearly over.

So what’s the answer to that heretical question?

The simple fact is it doesn’t really matter. I’m just very glad Hadrian’s Wall exists.

Douglas Jackson is the author of The Wall, published by Bantam Press, and eleven other novels set in Ancient Rome.

Aspects of History Issue 9 is out now.