In the winter of 1359 a young English soldier was taken prisoner during the siege of Reims, the holy city where French kings were anointed. The captive Englishman was a page in the household of Prince Lionel, one of the sons of King Edward III, and the siege was a (failed) operation during one of the King’s incursions across the Channel in pursuit of the French throne.

The teenage prisoner was Geoffrey Chaucer. Fortunately for him, medieval hostage-taking was more a matter of business than a way of depleting enemy numbers. Within a couple of months, the Keeper of the King’s Wardrobe paid £16 for Chaucer’s ransom. This was a useful sum – equivalent to around £8000 today – even if it was less than the King paid to recover a captured war-horse.

I used Chaucer’s capture and ransom as a starting-point for Chaucer and the House of Fame’, the first in a series of medieval mysteries featuring the great poet. In it, I imagine Chaucer returning to France a dozen years later and, as part of a secret mission, revisiting his old captor.

That £16 paid out on the orders of Edward III was a good investment. Geoffrey Chaucer would go on to serve the king, his family and his successor for most of the rest of his life, both at home and abroad. He undertook diplomatic missions to France and Italy and, probably, Spain, and no doubt these involved intelligence-gathering as well as conventional negotiation. While still in his early thirties he was put in charge of wool exports and the general flow of London trade, all overseen from a custom house on Wool Wharf close to the Tower of London.

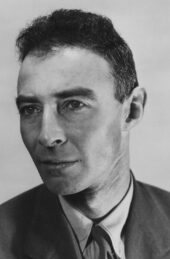

Depiction of Chaucer from the 19th century.

He’d been born and brought up not far away in the Vintry Ward, where his father John was a wine importer. The whole business of loading and unloading cargoes, checking manifests, assessing quality, watching out for sharp practice, all was familiar to him. So too must have been the pulse of travel. Boats arrived in London from as far away as Greece. Once a year a Venetian galley came to the port of London bearing spices.

In 1389, now with Richard II on the throne, Chaucer was appointed Clerk of the King’s Works, and so responsible for the upkeep of royal buildings from the Palace of Westminster to a hunting-lodge in the New Forest.

Altogether, Geoffrey Chaucer was the archetype of a senior civil servant. Yet his involvement with the royal family went deeper. His wife, Philippa, was a lady-in-waiting to Edward’s Queen (also Philippa). More importantly, his wife’s sister was Katherine Swynford, long-time mistress and eventual wife to John of Gaunt, another of Edward’s sons.

If Chaucer had been content to remain a courtier, book-keeper, civil-servant, then he would have been no more than a footnote in English history. But he was also the most influential poet of the medieval era. It’s traditional to think of poets as being head-in-the-clouds figures in real life. Clearly Chaucer was the very opposite of that.

The dates of his major works, Troilus and Criseyde and The Canterbury Tales, are uncertain but many lines must have been composed during a busy public life, and they reflect the energetic, shifting society which surrounded him.

Literally so, in the case of the Canterbury Tales, which begins with the poet in the Tabard Inn in Southwark, observing and then quickly befriending a group of pilgrims on the way to St Thomas’s shrine in Canterbury. They never get there. Chaucer’s wildly ambitious scheme which would have had each of the thirty travellers telling a story on the way out and the way back was less than a half fulfilled.

Nevertheless, what Chaucer did manage to write over several years is one of the most extraordinary feats in literature. Like the pilgrims, who range from decent and chivalrous to hypocritical and crooked, the tales strike all the notes from high to low. The best of them deserve rereading and retelling.

I’ve always thought of Chaucer as middle-aged. It may be because this is how he is traditionally depicted. It may be that he grew up fast during youthful military service. But in the end it’s more to do with the voice that comes across in his poetry: wry, worldly, sympathetic but not sentimental, ready to laugh at himself. Like his pilgrims, all too human and attractively so.

Philip Gooden is the author of the Geoffrey Chaucer Mysteries, published by Sharpe Books. Chaucer and the House of Fame is the first.