Marcus Licinius Crassus was famous for a boast. No one should be considered rich, said the richest Roman of his time, unless he could finance an army from his own income. Twice he lived up to that boast, the first time against Spartacus gaining himself only ingratitude, the second time beside the Euphrates costing his life and a national humiliation.

The man who I call ‘The First Tycoon’ was not content with being massively rich. Crassus was a money-man in the age of more conventionally successful men, Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, a pioneering banker who wanted also to match Rome’s greatest generals as a man of war. He was a long-time rival of Pompey and financier of Caesar (in many ways he had created him) but at the end of his life he wanted military glory of his own.

Crassus was a balancer of power at a time of savage instability, playing his fellow citizens against their rivals, big and small. In 53 BCE he had for thirty years worked innovatively behind the scenes of the political stage at Rome but his last and most lasting legacy was of his own severed head, stuffed with gold, as a prop in a tragic theatre thousands of miles away.

Crassus’s life was a classic tragedy of rise and fall. The first tycoon of ancient Rome would be remembered as its most famous loser. If he had died in 54 BCE he might have quietly entered history as Rome’s richest man, its first modern financier and political fixer, the brutal suppressor of Spartacus’s slave rebellion and a respected colleague of Caesar and Pompey at the pinnacle of power in Rome’s collapsing republic. His modern face would have been from 1960, Laurence Olivier in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

Instead, in 53 BCE, he led his banker’s army on an unprovoked campaign against the Parthian empire into what are now the borderlands of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. He lost a desert battle and the eagle standards of his legions near a small town called Carrhae. His head was said to have been filled with molten gold and used in a Greek tragedy when the plot required the remains of an arrogant king. The legacy of Crassus was a peculiarly catastrophic defeat that took a potent hold on the Roman mind.

Crassus was no ordinary failure, just as he had been no ordinary success – a man whose life as businessman and politician posed both immediate and lasting questions about the intertwining of money, ambition, and power. It is hard to write about him now and not think of Vladimir Putin, drawn to continuing disaster in Ukraine, for whom a legacy as a multi-billionaire ruler of Russia was not enough – and only matching Stalin or the greatest Tsars will do.

Crassus’s fortune came from exploiting the end of the civil wars in which he had lost his father and brother. From soon after his birth in 115 BCE, fifteen years before Caesar’s, his life was marked by the sight of heads on spikes as radicals and conservatives fought for power at Rome. In 83 BCE he had his best military success as an officer for the soon-to-be dictator, Lucius Cornelius Sulla. A messy triumph at the so-called Battle of the Colline Gate brought him the opportunity to buy the lands of the defeated and ‘proscribed’, to apply his own radical techniques of insurance and moneylending. Crassus was a subtle avenger. While others repaid past debts in blood, he bound thousands to him in getting and spending.

His getting was at first from the misfortunes of Sulla’s enemies, the spending, throughout his life, on those who might take their place in the power structures of Rome. His regular critic, the orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, likened the getting to a harvest; the spending was like the distribution of free food to the poor, an investment in gratitude. Crassus was an innovator at both, not least in living a comparatively modest life himself, despising the would-be rich who borrowed to buy his big houses, living in a single house at Romer with a wife who was his brother’s widow and two sons, one of whom joined him on the fatal journey to Carrhae.

His successful leadership of an army against Spartacus, an escaped gladiator who had extraordinarily become a threat to Rome, was an opportunity that came thirteen years after his victory at the Colline Gate. It was not, however, one that he, or any other potential commander, much relished. Pompey and Caesar were conveniently away when the crisis came. There would, they all knew, be no glory in defeating an army of slaves whom the Romans did not deign even to call an army. There could be no triumph, no applause in the streets, after a war which was not a war. Failure, on the other hand (and two allies of Pompey had already failed) would be the end for Crassus.

There was dangerously little cash in the state Treasury at the time. Crassus was the man who could raise, train and equip an army from his own resources. His property empire was as useful a training ground as any part of a foreign empire. He employed tens of thousands of slaves and recognised what, with good leadership, they could achieve. He respected Spartacus as others had not.

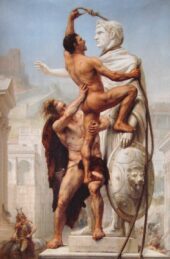

The death of Spartacus by Hermann Vogel

Crassus successfully crushed the rebellion, using his skills of organisation as much as any other. It was then his choice how to treat the prisoners who, unlike Spartacus himself, had survived the last battle. The long line of crucifixions between Capua, where the original escape took place, and the start of the Appian Way at the walls of Rome became the symbol by which two thousand years later Crassus would be most remembered. In 70 BCE it was a horror that Romans wanted as quickly as possible to forget.

There was, as he expected, no Triumph, merely a lesser honour, slightly enhanced by negotiation, in return for his huge investment of financial and political capital. Pompey even claimed a share of such honour that there was by mopping up a few rebel stragglers as he returned from Spain. Crassus could soon see Pompey and Caesar, with new wealth from conquest, as increasingly likely to exceed his influence at Rome. He himself remained far behind their reputations as conquerors.

Gradually the stage was set for what would become the fatal assault on Parthia. Crassus joined his rivals in an informal triumvirate that critics called the ‘Three-Headed Monster’. Each man had his own space in which to advance his ambitions without fear of hindrance by the others.

Parthia was a faraway land of which few Romans knew anything. It began in borderless zones east of the Euphrates and stretched without fixed end towards China. It was reputedly rich and prosperous; its barbarian rulers were members of a single fratricidal family; and the military intelligence available even to Crassus, the meticulous planner, was not much more than that. The idea of a Roman conquest was not new but there were plenty of nay-sayers (especially Cicero) and soothsayers (especially when the catastrophe at Carrhae had happened) who advised (or said that they advised) that the invasion plan should remain unused.

Crassus could not be dissuaded. He could afford his own army. His place at the top table of politics depended on its use. Caesar allowed Crassus’s son, who was serving heroically as a cavalry officer in Gaul, to bring horsemen for the Parthia force. Crassus planned and he drilled but he had little idea what he was preparing for or whom he would be fighting.

His humiliation was not inevitable. Like Vladimir Putin today, he was unlucky in his adversary. He might have expected to face a cynical elder of the Parthian royal family who would skirmish, retreat, cede territory, do a financial deal and wait to return when the Romans had tired and gone. Ukraine too had many would-be and has-been leaders of that sort from the Soviet era.

Instead he came up against a young and charismatic general called Surenas, the Zelensky of the desert one might say, who had a determination to defeat the Romans and his own innovative ways of doing so. In what became a compelling story for those who survived to tell it, Crassus entered a trap in which archers and armoured horsemen, with no infantry to match his legions, destroyed an army in direct contravention of every rule of Roman war.

The humble camel, not a beast much known to Crassus’s army, was deployed for reloading arrows in such a way as to turn every bow into an AK47. The deadly missiles came and kept on coming. Every legionary eagle standard was lost. Crassus saw the head of his son on a spike before dying himself in a desperate attempt to talk terms. Crassus’s own head was severed and taken back, with the eagles, to the Parthian king.

The barbarian court, or so it was said, was at the time of its arrival watching a performance of Euripides’s great Greek tragedy, The Bacchae (not a play ever performed for the proudly civilised of Rome) and the head of Crassus became a perfect stage prop for the scene when an arrogant king is torn apart by his mother’s maddened female band. In some versions its mouth was stuffed with molten gold. A look-alike Crassus was paraded in the closest approximation to a Roman triumph that the Parthians could produce.

Peter Stothard was editor of The Times, and the Times Literary Supplement and is a historian, journalist, critic, and the author of Crassus: The First Tycoon.