Barney White-Spunner, was your third book, having written previously about the military, why did you want to write Berlin?

I first went to Berlin as a soldier in the 1980s so well before the Wall came down. It made an immediate impact. It was not like anywhere I had been before in my previously rather sheltered life. Obviously the Wall created a specific tension but the whole place breathed a combination of excitement, anticipation, nervousness and the unexpected. So the book did originate in my military service but my fascination for this remarkable city meant that it grew into something more substantial and, I hope, more interesting. I like writing about things of which I have direct experience and Berlin has been particularly influential on me.

Berlin, the great capital of Germany, is endlessly fascinating, but in comparison to the other great capitals (London, Paris, Madrid, Rome and Athens) it is the youngster – do we know when it was founded?

Berlin started life as twin fishing villages on the River Spree, which is a fairly insignificant river when compared to the mighty Elbe or the Rhine, but there was an island near its junction with the Havel which was useful for trapping fish and wharfing boats. There has been a settlement here since history began, and at least from 2,000 B.C. This island slowly became a commercial centre that found itself at the junction of the north- south trade routes between the Hanseatic ports and Saxony and the west-east routes that serviced Poland. Clever use of markets and carriers meant that by the early middle-ages the twin villages were flourishing and Berliners take 1237 as being their official ‘founding’ as it’s the first written reference to the city. Yet Berlin did not achieve true significance until the Hohenzollerns bought the Mark of Brandenburg from the impoverished Emperor Sigismund in 1411 and made it their capital in 1415. Berlin was then the capital of Brandenburg until 1701, the capital of Prussia and from 1871 the capital of the German empire. From 1945 until 1989 it was the capital of East Germany and, since 1991, is now the capital of the Bundesrepublik.

It’s of course known today for both the brutal fighting in 1945, and its subsequent life at the sharp end of the Cold War – but what are the other parts of Berlin’s history that we should know more about?

Germans in general, and Berliners in particular, get rather annoyed that historians always focus on their 20th Century history, especially the twelve terrible years from 1933 and from 1945 until the Wall came down. Germany, or rather its constituent parts, did, they point out, have a rich history for many previous centuries. What I have tried to do is to tell the full story of Berlin from the middle-ages to the present day. I don’t believe that you can properly relate to the city unless you do understand its whole story. So many key events and movements in European history have their origins in Berlin. It was the sale of indulgences there that drove Luther to act, the 30 Years War had its greatest impact in the city, Marx was inspired by the terrible conditions in 19th century Berlin to articulate communism. Fascism sadly found its roots and its nemesis here and then it is Berlin that was the front line of the Cold War. Add to that an extraordinarily rich cultural and artistic history, especially as Berlin emerges as the centre of the German enlightenment, and you begin to appreciate just how important and interesting it is to know the full story.

Turning to the Nazi regime – Berlin was not a natural city of support for the Nazis was it?

Berliners mostly hated the Nazis and the Nazis hated Berlin. Hitler never forgave them for their lack of support in the 1933 election and most of those who did support him came from the outlying areas rather than the city itself. Hitler and Speer thought the city insufficiently grand to be the capital of their 1,000 year Reich and set about re-designing it, plans that were mercifully never fulfilled. The great set piece Nazi parades took place in Nuremberg rather than Berlin. Multi-cultural, multi ethnic Berlin, with its strong and emancipated Jewish population, was never going to be pro Nazi, and the street battles between the socialists and fascists of the 1920s and early 1930s, so well described by Isherwood, show a city that was more left than right. It was a city though that would suffer more than any from Hitler’s war, both from British and American bombing and from Soviet invasion and occupation.

Berliners suffered terribly at the hands of the Soviets in April/May ’45, and then in the years immediately after the war. How much does that history bleed through to its current participants, after all some buildings are still pockmarked from bullets and shrapnel?

One of the attractive features of Berlin is that it is a city that doesn’t try to hide its past; rather it incorporates it and lives with it. Some cities that have been badly damaged try to rebuild themselves as they wish they might have been rather than as they were. Berlin has never done that. Berliners are comfortable with their history, however savage it has been. Evidence of the Second World War is everywhere, from the still pockmarked buildings to the flak towers to the Nazi era buildings such as Goering’s ministry and the Olympic Stadium still in daily use. Then there is the Holocaust Memorial, absolutely central in the city and, although not to everyone’s taste, making an undeniable statement of grief and remorse. Not many cities would do that nor have a permanent museum of Nazi atrocities on the site of the old SS headquarters.

During the Cold War Berlin was its epicentre, how much of a challenge was it to go into extensive detail of this part of the city’s history?

It is an era which is surprisingly well documented and although it involved a lot of research it wasn’t difficult to find people to talk to or archives to explore. There are now two excellent if depressing Stasi museums in Berlin and, of course, so many people who lived through the DDR. One of the fads after 1989 was to research your own record in the Stasi files. Most people found theirs rather dull and surprisingly bland whereas a few had the shock of discovering that close friends and family had actually been spying on them. There have been a few excellent books published recently about life in the DDR such as Bridget Kendall’s The Cold War and Anna Funder’s Stasiland.

It was the capital of Prussia, but is not necessarily a Prussian city – what does that mean to those less familiar with its history?

It means that Berliners were never part of that militaristic Prussian tradition. Berlin has always been since its very earliest days, and still is, a city of immigrants. It is a city that has rebelled five times against its rulers. It was democratic when they were despotic, Lutheran when they were Calvinist, German when they were French, socialist when they were reactionary, avant-garde when they were conservative and wanted to be free when they were communist. Berliners found it ironic that many deputies in the Bundestag in Bonn were reluctant for the capital to move back to Berlin after 1989, arguing that Berlin had been the centre of first Prussian then Nazi militarism when in fact it led the resistance to both.

In today’s world, with war in eastern Europe and Russia the foe once again, what role does Berlin have to play – and do we appreciate its proximity to Russia, whereas its peers mentioned above are much further away?

Berlin is 30 miles from the Oder and the border with Poland. It was once roughly midway between the Prussian lands on the Rhine and the old Prussian capital of Königsberg but now its firmly in the east of the new Germany. It feels as much an eastern city as a western one, as it always has being on the boundary, the Mark – the frontier where Christianity met paganism, the Huns met the Slavs, Europe met Russia and where the fertile land met the sands, swamps and forests of Pomerania and Prussia. This gives Berliners a keener feeling for their eastern neighbours than is apparent in Paris or London, something which is often overlooked.

For any visiting Berlin, are there any particular landmarks, museums or locations you’d recommend the discerning history buff dedicate time to?

So many! Apart from the obvious great attractions, and the now exceptional museums which have been painstakingly restored since 1989, one of the great pleasures of Berlin are its lesser-known treasures which are often ignored by the busy visitor. The Jagdschloss Grunewald with its exceptional Cranachs; Königs Wusterhausen which is almost as Frederick-Wilhelm 1st. left it; the old medieval quarter with its churches; the Olympic Stadium and the Langemarckhalle; Sans Souci and Potsdam. The list is endless – but all is revealed in the book!

If a new edition were to be published, would you change anything?

The trouble with writing books like this is that you have to leave so much out! I would have loved to have made it two volumes but then I suspect not many people would have bought it if I had!

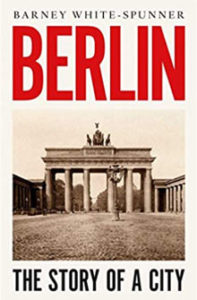

Barney White-Spunner is a historian and author of Berlin: The Story of a City which is highly recommended. You can listen to an interview with Barney White-Spunner on Berlin on the Aspects of History Podcast later this month.