‘… the sufferings of which were dreadful … when I awoke with that horror upon me …’

Charles Dickens had a cold. Man flu? One might wonder when reading the dramatic description of his anguish. But he was a novelist given to melodrama at times, and, considering the always present possibility of a cold turning to something more critical, we may, from our vantage point of unlimited supplies of paracetamol, feel some sympathy. Emily Bronte had a dreadful cold in the bitter winter of 1848 – look what happened to her.

On the cover of Thomas Dormandy’s book, The White Death, a history of tuberculosis, it is not surprising to see Branwell Bronte’s portrait of his sisters, painted in 1834. Emily and Anne look somewhat ethereal – they were never well. The winter of 1846 was bitterly cold. ‘The wind as keen as a two-edged blade’, so wrote Charlotte Bronte. Her sister Anne could hardly breathe, and a hacking cough kept her awake and exhausted. Charlotte writes of Anne’s ‘heroism of endurance’ as she watched her crouching over her desk, determined to complete The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

What is striking about the Victorian writers is their heroic fortitude in the face of illnesses; they sharpened their quills, dipped their pens, and wrote on, despite their colds, their asthma, their tuberculosis, rheumatism, gout, bladder problems, heart disease, and frequent nervous depression. And if the sickness was bad, the treatment was often worse.

Always practical, Dickens offered a remedy for his cold: ‘a teaspoon of sal volatile. A pinch of High Welch snuff, mixed together in a tumbler of water.’ Unpleasant but bearable.

Almost unbearable must have been the anal fistula which developed while he was writing Barnaby Rudge. The only treatment was to have it excised – without anaesthetic. Yet, he carried on, writing from his sofa. Dickens’s wore a flannel belt for his recurring kidney disease; when writing Bleak House, he was suffering from renal colic – the treatment was extract of henbane in alcohol. For repeated bouts of trigeminal neuralgia, he took laudanum. There was nothing else.

Sea air and laudanum were the answers to Mrs Gaskell’s neuralgia and migraines in 1850 when she was writing The Moorland Cottage, moving house, entertaining guests, and making flannel petticoats.

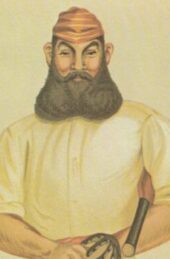

Charlotte Brontë

In December 1848, Emily Brontë refused to see any doctor until it was too late – nothing could reverse the disease: the painful breathing, the hectic fever, the visible weight loss. Emily died three months after Branwell succumbed. Two weeks after Emily’s death, Anne Bronte was diagnosed with advanced consumption. She was dosed with cod liver oil, cupped, blistered, and bled in her final weeks. Yet, she managed to finish her long poem: A Dreadful Darkness Closes In – very apt in the circumstances. The sea air of Scarborough could not cure her.

Charlotte battled on after her siblings’ deaths, writing her novels, enduring the pain between her shoulders, a recurring cough, fever, thirst, and poor appetite. She was dangerously ill during the writing of Villette in 1852 – a liver complaint was diagnosed. Mercury treatment nearly killed her. Her brief interval of marital happiness came to an end in 1855. The death certificate recorded ‘Phthisis’. She had wasted away. It is thought that the violent nausea occasioned by pregnancy was the cause of the wasting. Doctors could do nothing for her.

Dickens believed in hydrotherapy – he took a cold shower every day and drank a pint of cold water and walked and walked – sometimes seventeen miles a day. Thackeray was neither so abstemious nor so energetic. He confessed to drinking two bottles of wine a day with top-ups of punch and port, and brandy and soda before breakfast, and he loved his food. Thackeray suffered from a urethral stricture, the result of gonorrhoea, contracted probably as a result of a liaison in Paris with a cross-dressing former English governess. He was 18 at the time.

Thackeray’s bladder trouble pursued him all his life, and while writing Pendennis in 1849, he had cholera and a bladder infection. It took him six weeks to recover, his book brewing all the while in his mind, and he was writing a Christmas story, Rebecca and Rowena. He could not bear the idea of an operation. Perhaps he knew about the death of Dickens’s father. John Dickens had died as a result of a bladder operation. The cause of death was a rupture of the urethra from a long-standing stricture. Dickens had written that his father’s room was ‘a slaughterhouse of blood.’

William Makepeace Thackeray

No operation meant that Thackeray was frequently catheterised – he is very precise in his letters about whether a number 3 or 4 will do the trick. He took laudanum and calomel for repeated attacks of vomiting, and quinine for bouts of malaria, a condition he had picked up in Rome. In 1860, he was ill while writing Philip, and in 1863, he stayed in bed for thirty hours, laid up ‘with an instrument of torture in my urethra’, but he wanted to get on with his novel Denis Duval.

Thackeray was exceptionally tall for a Victorian at six foot three, but he was not strong. Anthony Trollope was a big man, too, but more robust. In his forties he weighed fifteen stone. Dickens walked for miles; Anthony Trollope rode to hounds. He was loud, good-humoured, and generally in sound health. He wrote an astonishing forty-seven novels. In later life, he wore a huge truss, suffered from asthma and was diagnosed with angina. Wilkie Collins was plagued with angina pains when writing his last complete novel, I say No, in 1884. The treatment was the inhalation of amyl nitrite, or steel filings in a bitter infusion were thought to be efficacious. It was recommended for gout, too – a purgative.

Trollope had his redoubtable mother’s example. Frances Trollope suffered from agonising pains in her shoulders, exacerbated by the long hours at her desk. Her writing was what kept the family from penury. At night copious draughts of laudanum kept her going.

A consequence of prolific laudanum use was constipation – back to the purgatives, necessary to maintain the excretory functions. Leeches were still used, along with mustard baths. And concerning the leech: Dickens’s artist friend, John (whose name was actually Leech), suffered brain fever from a bathing accident. Leeches were repeatedly applied and bread poultices for the leech bites. They didn’t work. Doctor Dickens cured him – with mesmerism.

Of the bowels – briefly – Tennyson’s in particular: Edward Fitzgerald observed of Tennyson that he was more concerned about his bowels than the ‘Laureate wreath’. Fitzgerald says that Tennyson was half-dead after taking the water cure at Malvern which involved being packed in sheets wrung out in cold water. Despite constant anxiety about his health, Tennyson wrote every day and died at the grand old age of eighty-three.

Wilkie Collins

Anyone would have turned to laudanum had they suffered from Wilkie Collins’s numerous ailments. Working on The Woman in White in 1859, he endured the lancing of a boil between his legs, earache, and rheumatic pains. Faintness, giddiness, and trembling accompanied the writing of No Name.

Like Thackeray, Collins loved his cigars and his food and drink – champagne, he believed was good for his health. It didn’t work. Nor did the vapour baths, the sulphur baths, the wormwood, the quinine, the potassium, the colchium, or the calomel. Calomel is chloride of mercury, commonly used to treat venereal disease. Too much could cause gangrene of the salivary organs and death. The poultice of cabbage leaves for Collins’s gouty foot didn’t do much good either. Dickens’s friend Doctor Elliotson tried mesmerism – to no avail. Collins’s most terrible affliction was gout in the eyes, so agonising at times that one friend described his eyes as ‘bags of blood’. Collins was so blinded by gout in 1868 that he had to dictate some part of The Moonstone. Only laudanum gave any relief. The doses increased so much so that Collins took enough to kill twelve people.

According to Victorian doctors, heart disease in men of studious habit was a result of overwrought minds and sedentary habits. The cure was to remove the patient from ‘evil and unnatural ways of life.’

Neither Collins nor Thackeray could give up the drink; Trollope couldn’t stick to his diet or give up his cigars; Dickens couldn’t give up his relentlessly gruelling public readings. None of them could give up their writing. Overwrought minds? Dickens died of a stroke at fifty-eight in the middle of writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood. At sixty-five, Wilkie Collins had a stroke and died of bronchitis – he was writing Blind Love. Thackeray died of apoplexy aged fifty-one – he didn’t complete Denis Duval. Trollope suffered a stroke and died a month later; he was sixty-seven. His last novel The Landleaguers was unfinished.

‘Take courage…’ were Anne Bronte’s last words to Charlotte. ‘Courage, persevere,’ said Dickens – often. So they did, sustained, perhaps, by a shot of Vin Mariani, a concoction of red wine and cocaine, the tipple of popes and Queen Victoria.

Jean Briggs is the author of At Midnight in Venice, part 5 of the Charles Dickens Investigations.

Drowned Woman